The curated resources linked below are an initial sample of the resources coming from a collaborative and rigorous review process with the EAD Content Curation Task Force.

Reset All

Reset All

Some issues are too fundamental for a party to withstand, and the consequences can last for a generation. This Learning Resource is a collaboration between New American History and Retro Report, producers of Upheaval at the 1860 Democratic Convention: What Happened When a Party Split.

The Roadmap

New American History

On the occasion of the launch of the Mandela Children’s Fund, Nelson Mandela said, “There can be no keener revelation of a society's soul than the way in which it treats its children.” Children have often been caught up and played a role in the ideological and political movements that have taken place throughout U.S. History. What can we learn about these political and ideological movements through the lens of children and their experiences? When we frame our study of the past through the experiences of children and adolescents, we create pathways for connection and curiosity for our students. There are many ways you might use these sources in your curriculum. Use these sources individually, as you cover a particular era, or collectively, as students examine change and continuity in the experiences of children and teens over time. Sources are indexed below by theme and era and each source includes a brief description as well as guiding questions for use in the classroom.

The resources in this spotlight kit are intended for classroom use, and are shared here under a CC-BY-SA license. Teachers, please review the copyright and fair use guidelines.

The Roadmap

- Primary Resources by SubthemeEducation and its Impact on Children and Teens (12)Children and Public Activism (7)

- Primary Resources by Era/DateColonial Era (3)Nineteenth Century (3)1930s - 1940s (3)1940s, 50s, and 60s (9)Early Twentieth Century and WWI (6)

- All 24 Primary ResourcesContract for the Indenture of Elizabeth Fortune, Aged 9, 1723Contract for the Indenture of Elizabeth Fortune, Aged 9, 1723Transcript

John Fortune and Maria his wife have by these presents put, placed, and bound their daughter Elizabeth Fortune aged nine years the first day of March last past as an apprentice with the Said Elizabeth Sharpas

as an apprentice with her, the said Elizabeth Sharpas, to dwell from the day of the date of these presents for and during the term of Nine Years…The Said Elizabeth Fortune unto according to her power, wit, and ability and honestly and obediently in all things shall behave herself towards her said Mistress and all hers and shall not contract matrimony during the said Term.

Elizabeth Sharpas for her part promises, Covenants, agrees that she the said Elizabeth Sharpas apprenticed Elizabeth Fortune in the art and skill of housewifery.

This document provides a glimpse into the experiences of colonial children who spent much of their childhood working for families that were not their own. This indenture arraignment also highlights the kinds of skills and education that were valued for girls. Namely, Elizabeth Fortune is said to receive training in the “art of housewifery” in exchange for her service.

CitePrintShare“Indenture of Elizabeth Fortune, September 10, 1723,” Women & the American Story, https://wams.nyhistory.org/settler-colonialism-and-revolution/settler-colonialism/children-at-work/#. Accessed 1 April 2022.

Needlework by Sarah Anne Janeway, 1783 - Training for domestic workSewn Sampler made by 11-year-old Sarah Anne Janeway, 1783Young colonial girls raised in wealthy households were trained in the skills of a housewife early on. Samplers like this one displayed a girl's aptitude for needlework and could be hung as a piece of art in a family household.

CitePrintShare“Symbols of Accomplishment - Women & the American Story.” Women & the American Story, https://wams.nyhistory.org/settler-colonialism-and-revolution/settler-colonialism/symbols-of-accomplishment/#. Accessed 1 April 2022.

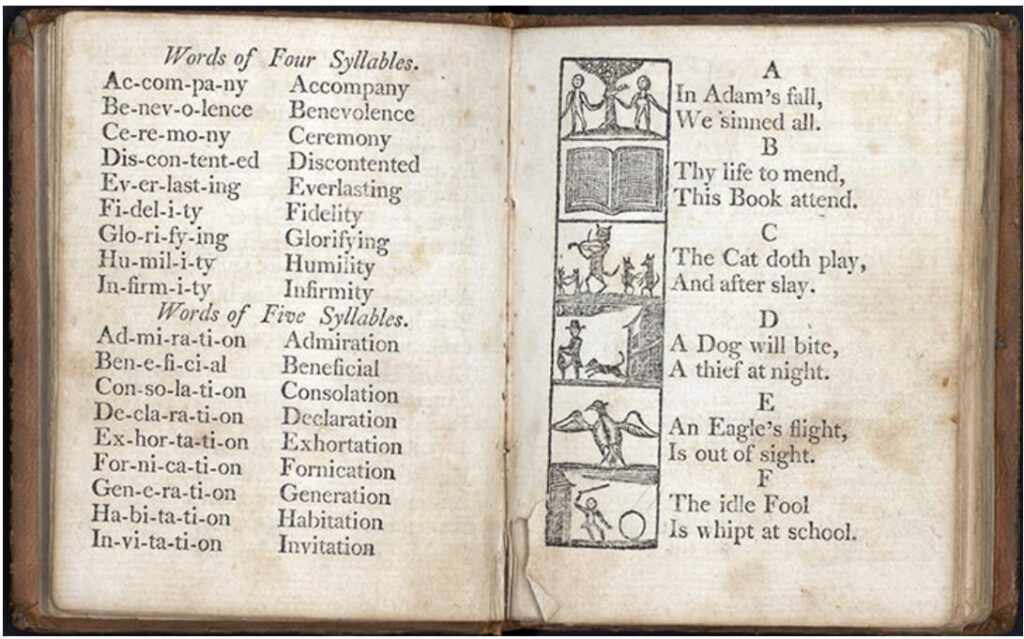

A New England Primer, 1803 - The role of religion in educationIn colonial New England, a primer like this one may have been in use as early as 1690. Children first learned their ABCs and basic literacy through primers. Since the Bible was seen as the primary means through which a child would attain literacy, these primers would often incorporate religious themes and morals.

CitePrintShareWestminster Assembly. “The New-England primer,” Boston: Printed for and sold by A. Ellison, in Seven-Star Lane, 1773. Pdf. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/22023945/>. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Perry Lewis (b. 1850), formerly enslaved, recounts his childhood in Baltimore, M.D. - Enslaved children and lack of access to educationPerry Lewis (b. 1850), formerly enslaved, recounts his childhood in Baltimore, M.D.TranscriptAs you know the mother was the owner of the children that she brought into the world Mother being a slave made me a slave. She cooked and worked on the farm, ate whatever was in the farmhouse and did her share of work to keep and maintain the Tolsons.

They being poor, not having a large place or a number of slaves to increase their wealth, made them little above the free colored people and with no knowledge, they could not teach me or anyone else to read…

In my childhood days, I played marbles, this was the only game I remember playing. As I was on a small farm, we did not come in contact much with other children and heard no childrens’ songs. I therefore do not recall the songs we sang.

Records from the Federal Writers Project are of immense importance in documenting and preserving the experiences of those who survived enslavement. ; Lewis’ account includes reference to the concept of hypodescent, which allowed intergenerational, chattel slavery to persist in the U.S. Lewis also makes note of his lack of access to education and some memories of his childhood.

1- Miletich, Patricia. “Religion and Literacy in Colonial New England | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.” Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History |, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/lesson-plan/religion-and-literacy-colonial-new-england. Accessed 2 April 2022.

- For more on the Federal Writer’s Project see Smith, Clint. “The Value of the Federal Writers' Project Slave Narratives.” The Atlantic, 9 February 2021, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2021/03/federal-writers-project/617790/. Accessed 19 April 2022.

CitePrintShareFederal Writers' Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 8, Maryland, Brooks-Williams. 1936. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/mesn080/>. Accessed April 2, 2022.

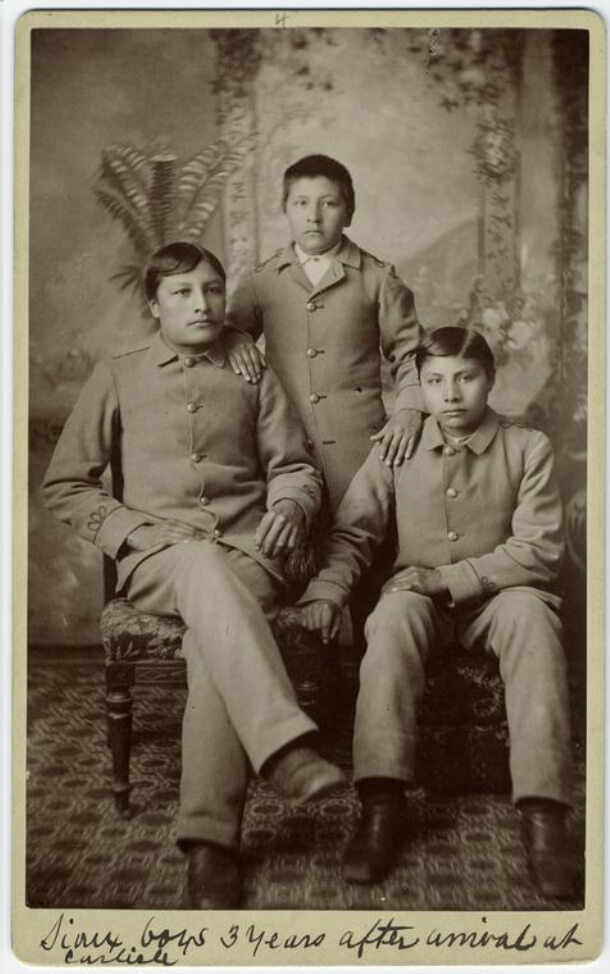

Before and After Photos of Children enrolled in Carlilse Residential Indian School, 1890s - Residential School SystemOne of the “before-and-after-education” photographs of Sioux boys taken before arriving at boarding school in the 1890s.At Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, and other residential schools like it, Native American children and teens were required to give up their tribal traditions and culture. Carlisle opened in 1879 as the first government-run residential school, aimed at forcing Indigenous youth to assimilate to White culture. These before and after photos were taken as a way to demonstrate the efforts at assimilation.

1- “Richard Henry Pratt Carlisle Indian School.” Carlisle Indian School Project, https://carlisleindianschoolproject.com/past/. Accessed 2 April 2022.

CitePrintShareImage 1: "Sioux boys as they arrived at Carlisle," Digital Public Library of America, http://dp.la/item/d7ca78d98ae563bfefd20c2620613c8b. Accessed April 2, 2022.

Image 2: "Sioux boys 3 years after arriving at Carlisle," Digital Public Library of America, http://dp.la/item/f7b6ae7adfd4a9c9ecbceaf3af5fa8b5. Accessed April 2, 2022.

Sample Program For One Week - Residential School SystemSample daily program for one week at an Indian school, 1914Life for a student at the Carlisle Indian School was highly regimented and militaristic, signaling the government’s influence on the school’s mission and identity. This source, paired with the images above, offers a glimpse into the daily experience of those enrolled in this program as well as information about the aims of the federal government in establishing institutions such as Carlisle.

CitePrintShare“Cover letter, January 23, 1914, with attached sample daily program for one week at an Indian school”; 1/1914; Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Record Group 75. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/cover-letter-january-23-1914-with-attached-sample-daily-program-for-one-week-at-an-indian-school. Accessed March 24, 2022.

Mary Ann Yahiro recites the Pledge of Allegiance at Raphael Weill School in San Francisco before being sent to Topaz internment camp in Utah, April 1942 - Japanese IntenmentMary Ann Yahiro, center, recites the Pledge of Allegiance at Raphael Weill School in San Francisco in April 1942 before being sent to Topaz internment camp in Utah.This photograph shows a group of children in the Weil Public School reciting the pledge of allegiance to the U.S. flag. The young girl in the front row center is Helen Mihara. A few months before this image was taken, Helen’s father, a San Francisco businessman, was arrested and detained in a Department of Justice camp for “enemy aliens.” Soon after this image was taken, Helen and her mother were placed in Tule Lake Relocation Center. Her mother later died in detention.

1- “San Francisco, Calif., April 1942 - Children of the Weill public school, from the so-called international settlement, shown in a flag pledge ceremony. Some of them are evacuees of Japanese ancestry who will be housed in War relocation authority centers for.” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2001705926/. Accessed 5 April 2022.

CitePrintShareLange, Dorothea, photographer. San Francisco, Calif., April- Children of the Weill public school, from the so-called international settlement, shown in a flag pledge ceremony. Some of them are evacuees of Japanese ancestry who will be housed in War relocation authority centers for the duration. [April] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2001705926/>. Accessed April 10, 2022.

TIME Magazine Feature on the American “teen-ager," 1944 - American Teenage Girls“The Invention of the American “teen-ager,” 1944Although it is not a certainty, some historians believe that the concept of the American “teenager” originated sometime in the 1940s. A liminal age, the teenager was neither child nor adult. This 1944 TIME Magazine article detailed the “life of the American Teenager” by photojournalist Nina Leen. The full article offers a glimpse into the perception of teens but also offers opportunities for students to consider the rise of the middle class, social status, and race in the middle of the twentieth century.

Separate but Unequal: Two classrooms before Brown v. Board of Education, Georgia, 1941 - School SegregationSchool segregation was among the most central concerns of the Civil Rights Movement since the 1930s. Activists for school integration argued that separate was not equal and every child, regardless of race, was entitled to education in a safe learning environment. These two images depict daily life in segregated classrooms in the same year, 1941. Brown v. Board of Education would not be passed for more than a decade.

1- “Recovery Programs.” Recovery Programs | DPLA, https://dp.la/exhibitions/new-deal/recovery-programs/farm-security-administration?item=409. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShareImage 1: Delano, J., photographer. (1941) Veazy, Greene County, Georgia. The one-teacher Negro school in Veazy, south of Greensboro. United States Greene County Georgia Veazy, 1941. Oct. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017796657/. Accessed April 10, 2022.

Image 2: Delano, J., photographer. (1941) Siloam, Greene County, Georgia. Classroom in the school. United States Greene County Siloam Georgia, 1941. Oct. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017796554/. Accessed April 10, 2022.

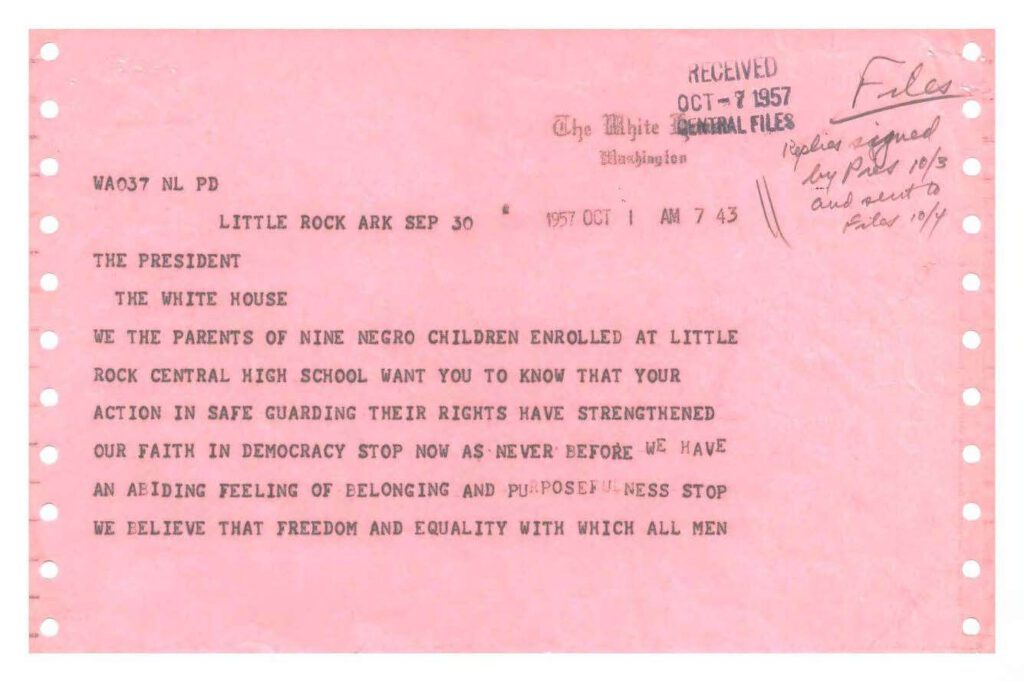

Telegram from Parents of the Little Rock Nine to President Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1957-58 - School IntegrationTelegram from Parents of the Little Rock Nine to President Dwight D. EisenhowerWritten three years after the passage of Brown v. Board of Education, this telegram to President Eisenhower details the feelings of parents of the Little Rock Nine, who were a part of the busing program to integrate the Little Rock school system. The Little Rock Nine were the first African American students to enter Little Rock’s Central High School in Arkansas. The parents note that because of the supreme court ruling their “faith in democracy” had been renewed.

1- “The Little Rock Nine.” National Museum of African American History and Culture, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/little-rock-nine. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShareTelegram from Parents of the Little Rock Nine to President Dwight D. Eisenhower; 10/1957; OF 142-A-5 Negro Matters - Colored Question (5), 1957 - 1958; Official Files, 1953 - 1961; Collection DDE-WHCF: White House Central Files (Eisenhower Administration), 1953 - 1961; Dwight D. Eisenhower Library, Abilene, KS. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/telegram-parents-little-rock-nine-to-president-eisenhower. Accessed April 1, 2022.

African American children on their way to PS204, 82nd Street, and 15th Avenue, pass mothers protesting the busing of children to achieve integration, 1965 - School IntegrationAfrican American children on their way to PS204, 82nd Street, and 15th Avenue, pass mothers protesting the busing of children to achieve integrationEven after the passage of Brown v. Board of Education, school integration was protested. This image shows African American children entering their new school while white mothers protest school integration

CitePrintShareDemarsico, Dick, photographer. African American children on way to PS204, 82nd Street and 15th Avenue, pass mothers protesting the busing of children to achieve integration (1965). Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2004670162/>. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Audio Recording: Conversation with 11 and 12-year-old black females, Meadville, Mississippi, 1973 - Daily life for two pre-teens in DetriotThis conversation was originally recorded as part of an effort to archive regional dialects by the Library of Congress. It also provides a glimpse into the daily lives of pre-teen girls, including racial discrimination they faced in their school community.

Audio Recording: Conversation with 11 and 12-year-old black females, Meadville, Mississippi

CitePrintShareUnidentified, and Walt Wolfram. Conversation with 11 and 12-year-old black females, Meadville, Mississippi. to 1973, 1972. Audio. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/afccal000213/>. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Mother Jones and Children Laborers go on Strike, 1903Mother Jones and Children Laborers go on Strike, 1903In July of 1903, Mother Jones led a march from Philadelphia to the home of President Rosevelt to protest the unsafe labor conditions of children working in mills. The story of Mother Jones and the children who accompanied her on her march showcases not only youth activism but also women in the labor movement at the turn of the century.

1- Lauren Cooper. “July 7, 1903: March of the Mill Children.” Zinn Education Project, https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/mother-jones-march-mill-children/. Accessed 3 April 2022.

CitePrintShare"Mother" Jones and her army of striking textile workers starting out for their descent on New York The textile workers of Philadelphia say they intend to show the people of the country their condition by marching through all the important cities”; 1903; Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2015649893/. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Child Labor Standards, 1916Child Labor StandardsThis ad was created after the passage of the Keating-Own Child Labor Act of 1916. This act limited the working hours of children and placed an age requirement of the age of 16 for any working child. It also forbade the interstate sale of goods produced in factories that employed child labor.

CitePrintShare"Child Labor Standards"; ca. 1941-1945; Records of the Office of War Information, Record Group 208. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/child-labor-standards. April 1, 2022.

Girl Scouts and the War EffortGirl Scout Troup Plants a Victory Garden, 1917Girl Scout Pledge Card to Save for a Soldier, 1914After the US declared war in 1917, children were encouraged to support the war efforts. The Girl Scouts of America provided an opportunity for girls to become involved in volunteer work for the war effort. Organizations like the Girls Scouts and 4H typically trained girls for domestic work. Skills like sewing and first-aid were put to use in new ways for members of the Girl Scouts and 4H during WWI. Here, scouts planted a Victory Garden. Victory gardens, or liberty gardens, first appeared during WWI. The federal government encouraged citizens to plant vegetable gardens to mitigate any food shortages that resulted from the war.

1- Lauren Cooper. “July 7, 1903: March of the Mill Children.” Zinn Education Project, https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/mother-jones-march-mill-children/. Accessed 3 April 2022.

- Spring, Kelly A. “Girls' Volunteer Groups during World War I.” National Women's History Museum, https://www.womenshistory.org/resources/general/girls-volunteer-groups-during-world-war-i. Accessed 3 April 2022.

CitePrintShareImage 1: Harris & Ewing, photographer. NATIONAL EMERGENCY WAR GARDENS COM. GIRL SCOUTS GARDENING AT D.A.R. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2016867777/>. Accessed April 2, 2022.

Image 2: “Girl Scout Pledge Card "To Save for a Solder”. 1914. Girl Scout Archive Management Center. https://archives.girlscouts.org/Detail/objects/64958. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Boy Scouts as Bond Workers, 1917Boy Scouts as Bond Workers, 1917Boyscouts, like Girl Scouts, volunteered in the war effort during both WWI and II. Here, scouts who were too young to go to combat sell war bonds.

CitePrintShareBain News Service, Publisher. Boy Scouts as bond workers. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2014704734/>. Accessed April 10, 2022.

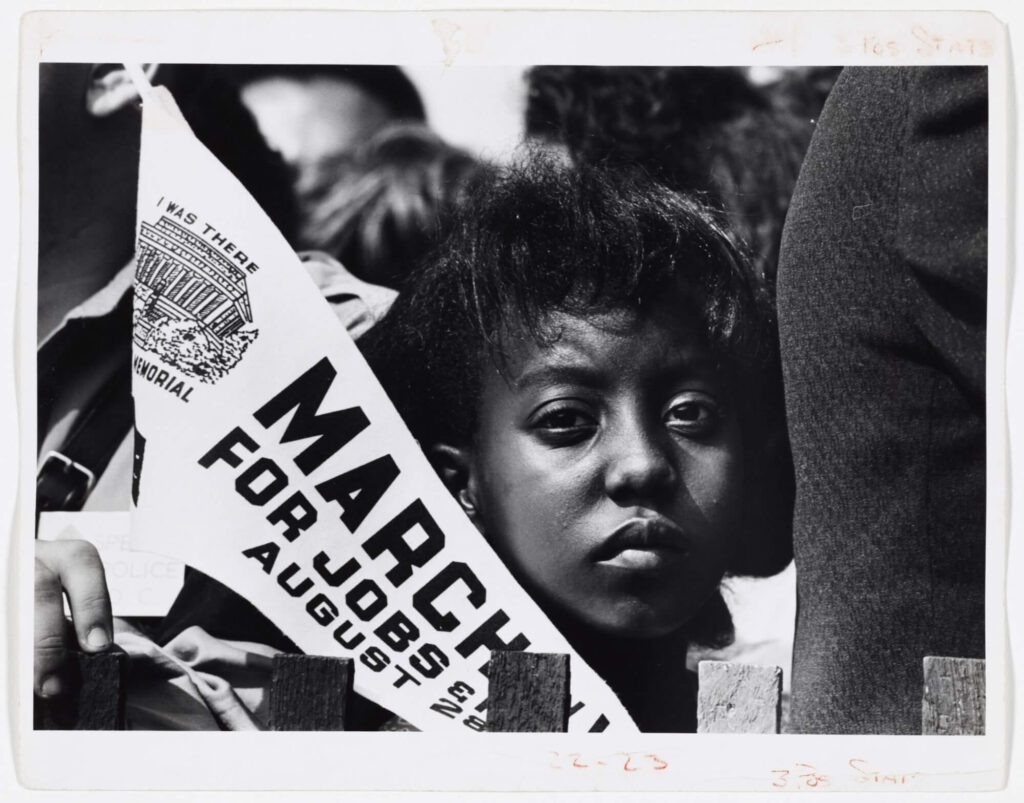

12-Year-Old Girl at the March on Washington, 196312-Year-Old Girl at the March on WashingtonOn August 28, 1963, thousands took part in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The March was instigated by a continuing lack of jobs for African Americans and the persistence of segregation. The march was influential in pressuring President John F. Kennedy to draft a strong civil rights bill. This photo depicts Edith Lee-Payne on her twelfth birthday. Edith attended the March with her mother.

1- “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom | The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute.” The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute |, https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/march-washington-jobs-and-freedom. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintSharePhotograph 306-SSM-4C-61-32; Young Woman at the Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. with a Banner; 8/28/1963; Miscellaneous Subjects, Staff and Stringer Photographs, 1961 - 1974; Records of the U.S. Information Agency, Record Group 306; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/girl-march-on-washington-banner. Accessed April 1, 2022.

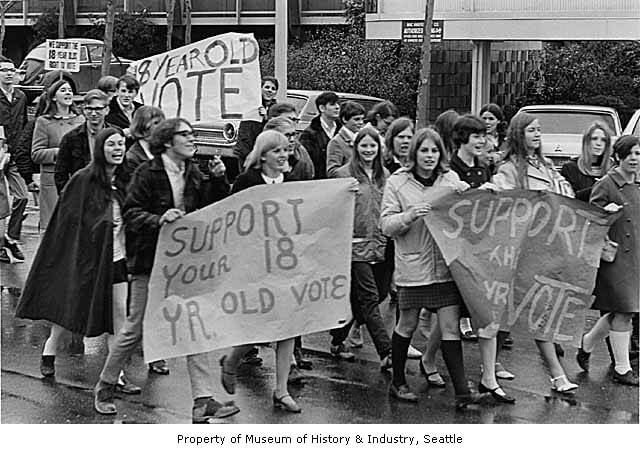

Protests in support of the 26th Amendment, 1969Protests in support of the 26th AmendmentThe 26th Amendment to the Constitution allowed for those 18 years old or older to vote in elections. Support for decreasing the voting age from 21 to 18 increased during World War II, as young men were conscripted to fight in the war as young as 18 but could not yet vote. This image depicts youth protestors in support of the 26th amendment.

1- “The 26th Amendment | Richard Nixon Museum and Library.” Nixon Presidential Library, 17 June 2021, https://www.nixonlibrary.gov/news/26th-amendment. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShare“Demonstration for reduction in voting age, Seattle, 1969”; Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, Museum of History & Industry, Seattle; https://digitalcollections.lib.washington.edu/digital/collection/imlsmohai/id/1715/. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Little Spinner in Globe Cotton Mill, Augusta, Ga., 1909Little Spinner in Globe Cotton Mill, Augusta, Ga., 1909Images of children laborers at the turn of the century reveal the experiences of children who spent most of their days working in the oftentimes harsh and unsafe conditions of urban factories. After the Civil War, as industry grew in urban areas, children often worked in factories, in markets, and on the streets as vendors.

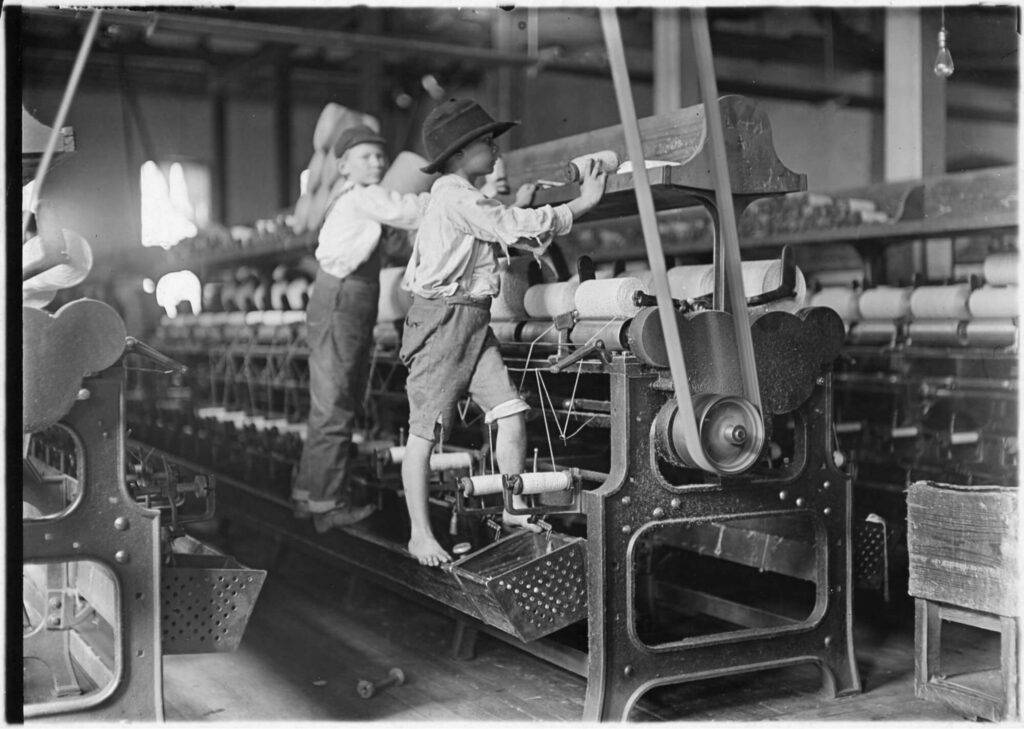

Children Working in a Textile Mill in Georgia, 1909Children Working in a Textile Mill in GeorgiaLike the image above, this source shows a young child operating machinery that he is not even tall enough to reach. Images like these and the one above were captured by activists for child labor laws. The Child labor standards act would be passed in 1916

1- Schuman, Michael. “History of child labor in the United States—part 1: little children working: Monthly Labor Review: US Bureau of Labor Statistics.” Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2017/article/history-of-child-labor-in-the-united-states-part-1.htm. Accessed 19 April 2022.

CitePrintSharePhotograph 102-LH-488; Bibb Mill No. 1, Macon, Ga.; 1/19/1909; Bibb Mill No. 1, Macon, Ga. Many youngsters here. Some boys and girls were so small they had to climb up onto the spinning frame to mend broken threads and to put back the empty bobbins.,; Records of the Children's Bureau, Record Group 102; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/bibb-mill. Accessed April 1, 2022.

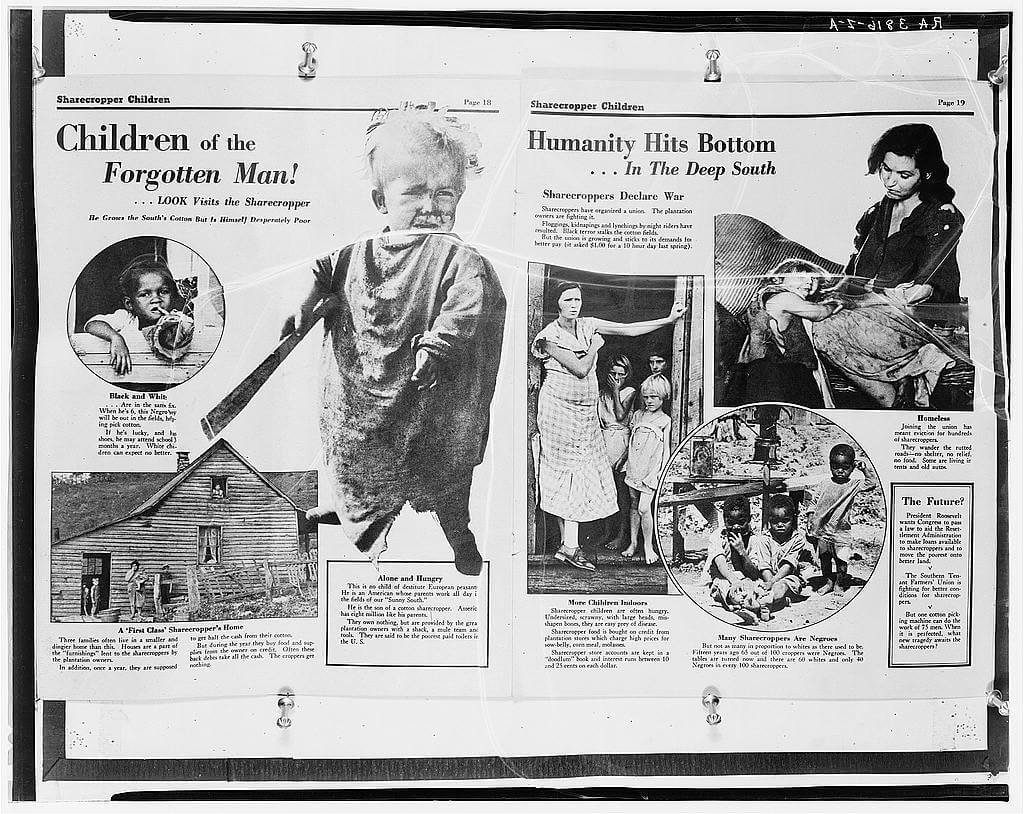

Spread from Look magazine on sharecropping children, 1937Page from Look magazine, 1937 on sharecropping childrenThis magazine spread on sharecropping children was published the same year that President Rosevelt established the Farm Security Administration. The FSA was a New Deal agency that provided assistance and relief to agricultural workers impacted by drought and the Great Depression.

1- “Gardening for the Common Good.” Smithsonian Libraries, https://library.si.edu/exhibition/cultivating-americas-gardens/gardening-for-the-common-good. Accessed 19 April 2022.

CitePrintSharePages 18 and 19 of March Look magazine. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2017760274/>. April Accessed April 10, 2022.

Boys playing marbles, Farm Security Administration labor camp, Robstown, Texas, 1944Boys playing marbles, Farm Security Administration labor camp, Robstown, Texas, 1944During the Great Depression, The Farm Security Administration attempted to aid workers and farmers by setting up housing camps, providing loans and training to workers, among other forms of assistance. This source shows a group of children playing marbles in one of the FSA labor camps in Texas, offering a glimpse into daily life and play for children living through the Great Depression.

CitePrintShareRothstein, A., photographer. (1942) Boys playing marbles, FSA ... labor camp, Robstown, Texas. United States Robstown Texas, 1942. Jan. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017877649/. Accessed April 10, 2022.

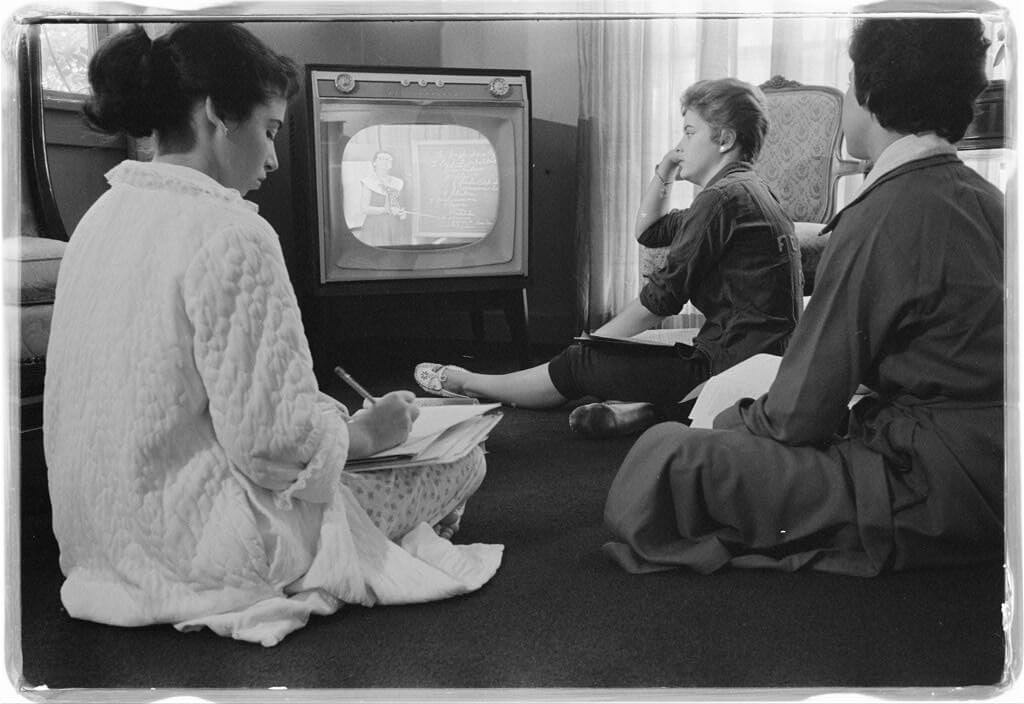

School Closures during Little Rock Nine: Girls learn from Home, 1958 - School IntegrationSchool Closures during Little Rock 9: three pajama-clad white girls being educated via television during the period that the Little Rock schools were closed to avoid integration.In September 1958, Governor Faubus of Arkansas closed all Little Rock public high schools as a result of unrest due to integration. Known as the “Lost Year,” both teachers and students were blocked from their school buildings. This image shows three girls learning “remotely” during that time and offers a glimpse of the efforts to maintain continuity of education in the midst of upheaval.

1- “The Little Rock Nine.” National Museum of African American History and Culture, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/little-rock-nine. Accessed 4 April 2022.

- “Sept. 12, 1958: Little Rock Public Schools Closed.” Zinn Education Project, https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/little-rock-schools-closed/. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShareO'Halloran, T. J., photographer. (1958) Little Rock, Ark. Attempts to reopen schools / TOH. Arkansas Little Rock, 1958. Sept. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2003654390/. Accessed April 1, 2022.

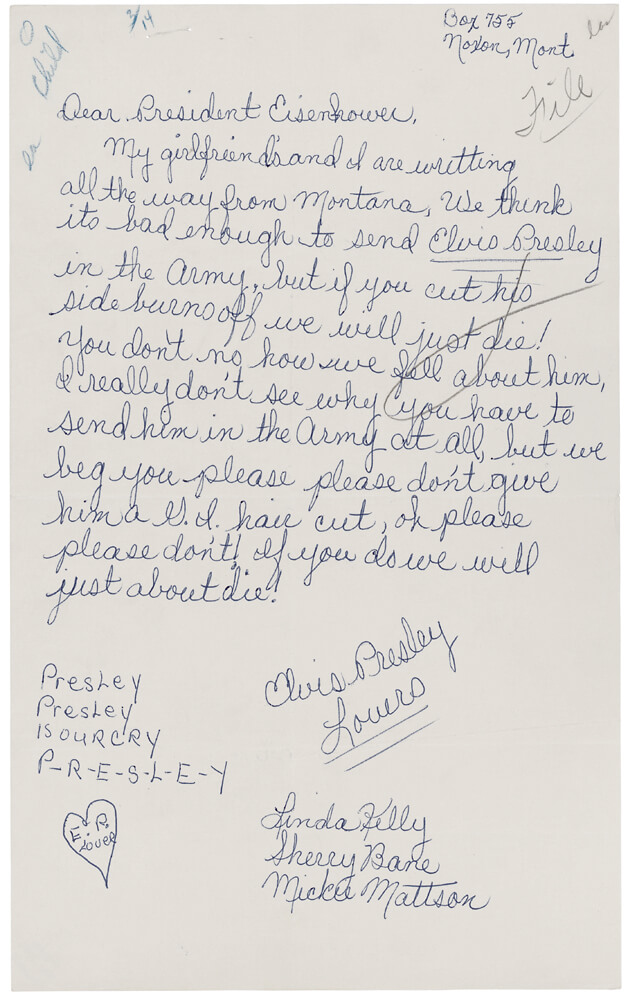

Letter from Linda Kelly, Sherry Bane, and Mickie Mattson to President Dwight D. Eisenhower Regarding Elvis Presley, 1953-1961Letter from Linda Kelly, Sherry Bane, and Mickie Mattson to President Dwight D. Eisenhower Regarding Elvis Presley, 1953-1961Celebrities were no exception to the draft during the Vietnam War. Elvis Presley joined the army in 1958 and, in this letter, three girls from Nevada ask President Eisenhower not to shave off his sideburns. This source offers a window into the lives of American teens as well as an example of the role teens played in the evolution and development of American pop culture.

1- Cosgrove, Ben. “The Invention of Teenagers: LIFE and the Triumph of Youth Culture.” Time.com, TIME, 28 September 2013, https://time.com/3639041/the-invention-of-teenagers-life-and-the-triumph-of-youth-culture/. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShareBane, Sherry Author, Linda Author Kelly, and Mickie Author Mattson. Letter from Linda Kelly, Sherry Bane, and Mickie Mattson to President Dwight D. Eisenhower Regarding Elvis Presley. [Place of Publication Not Identified: Publisher Not Identified, 1958] Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2021667581/> Accessed April 4, 2022.

- Additional Resources

- Teacher's Guides and Analysis Tool | Getting Started with Primary Sources | Teachers | Programs | Library of Congress

- Document Analysis Overview | National Archives

- Activity Tools | DocsTeach

- Primary Source Activity Guide | EAD Team

Education for American Democracy

This lesson asks students to investigate the connections between constitutional principles, the United States founding documents, and their relationship to one another.

The Roadmap

Bill of Rights Institute

The resources in this collection support students to engage with news on themes like global immigration, democracy, and racial justice in the United States while building their capacities for critical thinking, emotional engagement, ethical reflection, and civic agency.

The Roadmap

Facing History and Ourselves

Gain a deeper understanding of the 14th Amendment and the evolution of Title IX by analyzing the Supreme Court's 1984 decision in Grove City College v. Bell

The Roadmap

Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts

With ever-evolving media, visual images play a significant and powerful role in moments of social change. This spotlight kit, made up almost entirely of primary source images ripe for visual analysis, focuses on moments of protest and resistance to government policies and other symbols of authority. Resources include images of events, movements and moments of resistance from the mid-20th to the early 21st centuries. In these moments, photographs and other media play the dual role of capturing the message and, in helping to spread its visibility, contributing to the fight for social change.

This image-based Spotlight Kit lends itself particularly well to a range of uses in the classroom: as an inquiry activity to introduce an historic era or the theme of protest; with diverse learners, including students with identified language processing disorders or students who are English Language Learners; and as a supplement to other text-based primary sources.

While no set of images can comprehensively capture any era, these particular examples were selected for their intentional use of visual media or the ways in which these moments have become symbolic and iconic. The images also include powerful slogans used by activists, many of which connect and echo across different events in this collection.

The resources in this spotlight kit are intended for classroom use, and are shared here under a CC-BY-SA license. Teachers, please review the copyright and fair use guidelines.

The Roadmap

- Primary Resources by Decade1955-1960s (4)1970s-1980s (7)2000-2022 (10)

- All 21 Primary ResourcesMamie Till Mobley weeps at her son's funeral (1955)Mamie Till Mobley weeps at her son's funeral on Sept. 6, 1955, in Chicago. Mobley insisted that her son's body be displayed in an open casket forcing the nation to see the brutality directed at Blacks in the South. AP, FILE

Following the lynching murder of her fifteen-year-old son, Emmett Till,, Mamie TIll Mobley insisted on an open casket at his funeral; according to Time magazine, “When Till’s mother Mamie came to identify her son, she told the funeral director, ‘Let the people see what I’ve seen.’” The graphic images of his beaten body captured the attention of people across the United States, and the photo’s publication in Jet magazine is widely considered a galvanizing moment for the Civil Rights Era.

CitePrintShareShapiro, Emily. “Emmett Till's childhood home is named a Chicago landmark.” ABC News, 28 January 2021, https://abcnews.go.com/US/emmett-tills-childhood-home-named-chicago-landmark/story?id=75536520.

“The Photo That Changed the Civil Rights Movement.” TIME, 10 July 2016, https://time.com/4399793/emmett-till-civil-rights-photography/.

The March on Washington (1963)The March on Washington, 1963The March on Washington, 1963 By 1963 the Civil Rights Movement had grown substantially. They had support for both the black and white communities, as well as many celebrities. The purpose of this march was to gain national support for legislation in Congress. One of the most famous moments of the march was Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s “I Have a Dream” speech. Originally proposed in 1941 as the “March for Jobs and Freedom” by A. Philip Randolph, photographs of the March became – and remain – some of the most iconic images of the Civil Rights Movement.

CitePrintShareLeffler, W. K., photographer. (1963) Civil rights march on Washington, D.C. / WKL. Washington D.C, 1963. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2003654393/.

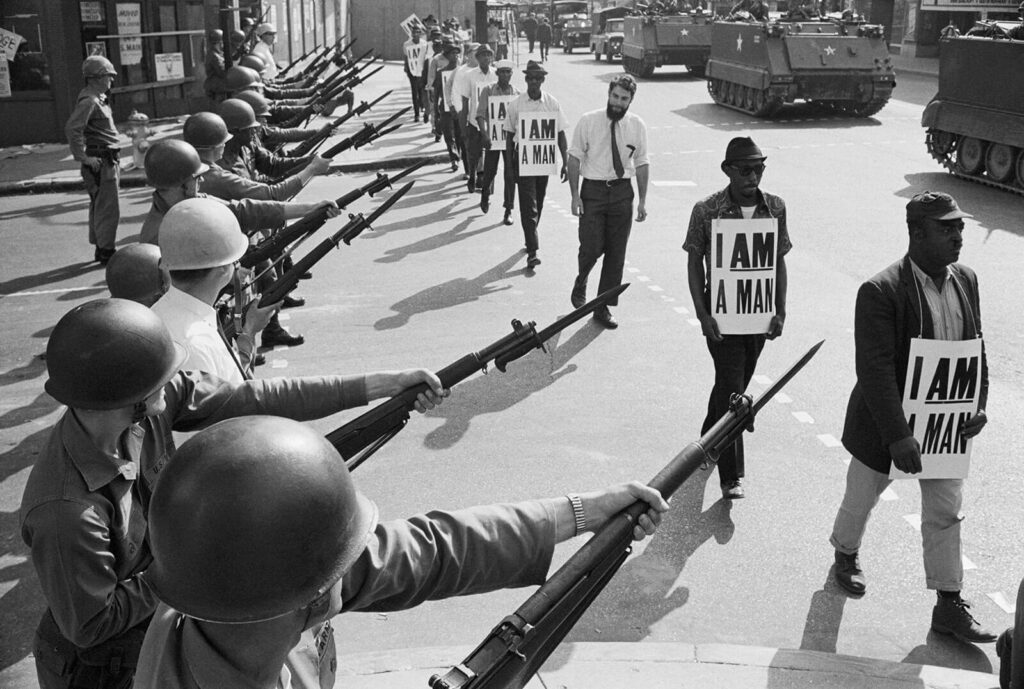

Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike (1968)US National Guard troops block off Beale Street in Memphis, Tennessee, as civil rights protesters march for the third day in a row. Bettmann/Getty Images (March 29, 1968)Any number of images from the Civil Rights era would benefit a unit on freedom of speech, but this particular image does a few things: (1) it marks the occasion immediately before Martin Luther King’s assassination; (2) it provides an image of a single text used over and over, in contrast to the image above with multiple demands; and (3) it juxtaposes protesters exercising their first amendment rights with National Guard troops wielding weapons.

CitePrintShare“1968: The year in pictures.” CNN, https://www.cnn.com/interactive/2018/05/world/1968-cnnphotos/. Accessed 26 February 2023.

John Carlos and Tommie Smith raise fists in protest as they receive their Olympic medals (1968)John Carlos and Tommie Smith raise fists in protest as they receive their Olympic medals (1968)Aware of the platform provided by international television coverage of the Olympics, medal-winning U.S. track athletes John Carlos and Tommie Smith chose to raise a fist during their medal ceremony to protest racial inequality in the country they were representing, at the very moment the Star Spangled Banner was playing.

CitePrintShareLayden, Tim. “John Carlos, Tommie Smith: 1968 Olympics black power salute.” Sports Illustrated, 3 October 2018, https://www.si.com/olympics/2018/10/03/john-carlos-tommie-smith-1968-olympics-black-power-salute.

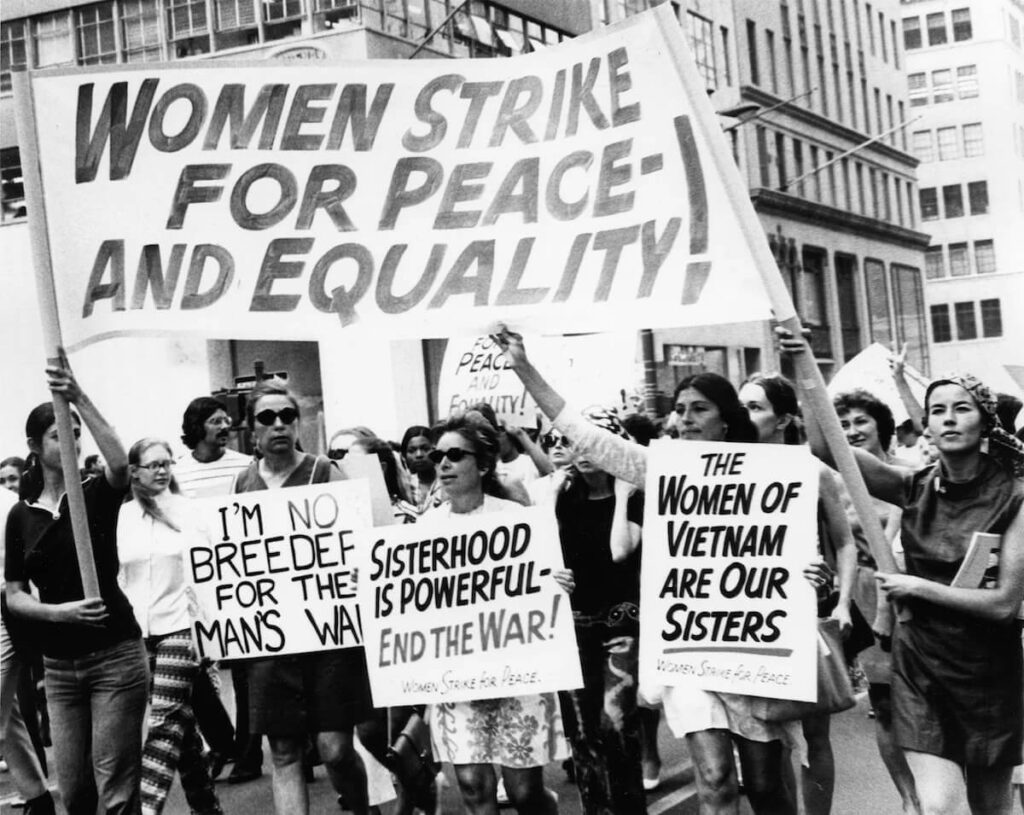

Women's Strike for Peace and Equality (1970)Women's Strike for Peace and Equality, New York City, Aug. 26, 1970. Eugene Gordon—The New York Historical Society / Getty ImagesThe 1970s Women’s Strike was organized by feminist author Betty Friedan, to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the 19th Amendment, which prevented women from being denied the vote “on the basis of sex.” As reported by Time, “Friedan’s original idea for Aug. 26 was a national work stoppage, in which women would cease cooking and cleaning in order to draw attention to the unequal distribution of domestic labor, an issue she discussed in her 1963 bestseller The Feminine Mystique. It isn’t clear how many women truly went on ‘strike’ that day, but the march served as a powerful symbolic gesture. Participants held signs with slogans like ‘Don’t Iron While the Strike is Hot’ and ‘Don’t Cook Dinner – Starve a Rat Today.’”

CitePrintShareCohen, Sascha. “Women's Equality Day: The History of When Women Went on Strike.” Time, 26 August 2015, https://time.com/4008060/women-strike-equality-1970/.

Poster image from “Women's Strike for Equality.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women%27s_Strike_for_Equality.

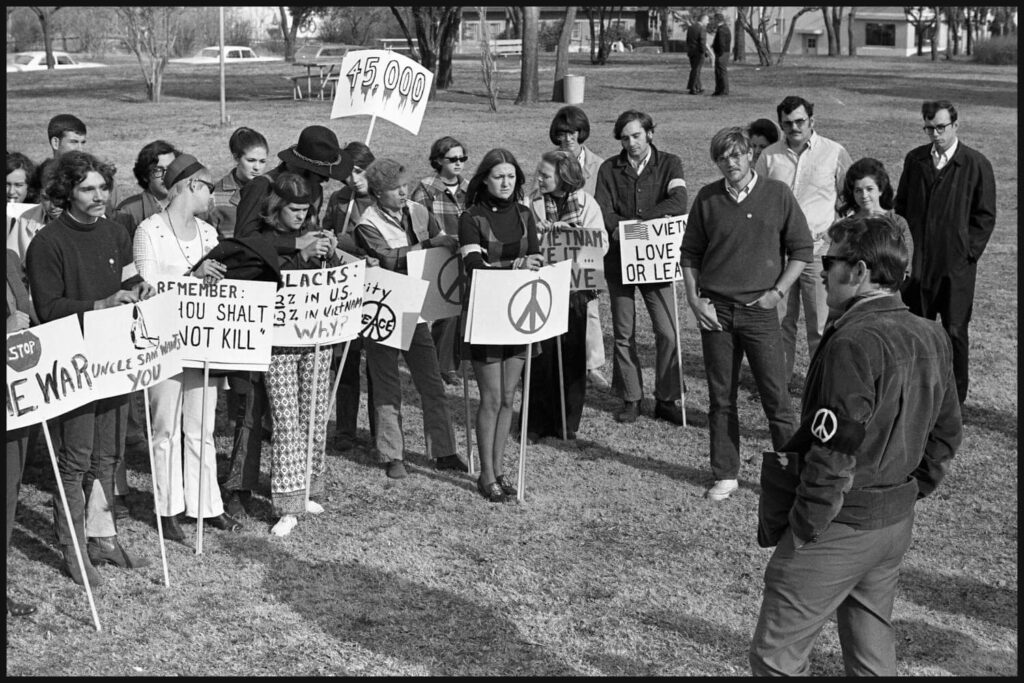

Protests against the Vietnam War (1969-70)Protest against the Vietnam War, Texas, December, 1969. Credit: Jimmy Cochran.Antiwar march October 31, 1970, Seattle, two months after the death of Reuben Salazar in the Los Angeles Chicano Moratorium protestVietnam War Protests The Vietnam protest movement represented a growing anti-war movement in the United States in the late 1960s to early 1970s. Protestors spanned the racial spectrum and employed varying methods to end the war in Vietnam, started by the United States.

In many cases, anti-war protests combined with efforts to turn attention to domestic issues. As described in the Mapping American Social Movements Project of the University of Washington, “Chicanos in Los Angeles formed alliances with other oppressed people who identified with the Third World Left and were committed to toppling U.S. imperialism and fighting racism…. The Chicano Moratorium antiwar protests of 1970 and 1971…reflected the vibrant collaboration between African Americans, Japanese Americans, American Indians, and white antiwar activists that had developed in Southern California.”

CitePrintShareCochran, Jimmy W. “[Line of Protesters Against Vietnam War] - The Portal to Texas History.” The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth1276191/.

Estrada, Josue. Chicano Movement Geography - Mapping American Social Movements, https://depts.washington.edu/moves/Chicano_geography.shtml.

Disability Rights Movement Protest for the Rehabilitation Act (1973)Disability Rights Movement Protest for the Rehabilitation Act 1973, photographer Tom Olin Greyhound Bus Depot in Los Angeles, Diane Coleman, Steve Remington and Rick Wilson.The Civil Rights Movement for Black equality inspired many other movements, including a national push for disability rights. The Rehabilitation Act of 1973 prohibited discrimination on the basis of disability and protected equal access for people with disabilities in areas including public services, employment, and education.

CitePrintShare“History and Timeline | Department on Disability.” Department on Disability, https://disability.lacity.org/resources/celebrate-ada-30th-anniversary/history-and-timeline.

Protests for and against the Equal Rights Amendment (1973)Protests led by Phyllis Schlafly, center, opposed the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment, 1973.Women supporting the ERA carry a banner down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington DC on August 26, 1977The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) states: "Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex." First proposed as an Amendment to the Constitution in 1923, Congress finally passed the ERA in 1972. The senate vote was overwhelming: 84 to 8. The Amendment then went to state legislatures for approval, requiring 38 for ratification. 22 states ratified in that first year, and 8 more in 1973. But then a grassroots opposition movement made significant inroads. 35 states eventually approved it by 1977, but the passage of the Amendment then stalled and the deadline expired in 1982.

In these photos, women who fought both for and against the Amendment’s passage are pictured protesting. In the top photograph, American attorney and conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly, founder of STOP-ERA, leads a protest against the Amendment. In the bottom photograph, women dressed in white – evoking suffragists of the past – protest in favor of the Amendment in Washington, DC on August 26, 1977 – the same date of the Women’s Strike seven years earlier (also included in this Spotlight Kit).

CitePrintShare“ERA wouldn't be good for women | Tuesday's letters.” Tampa Bay Times, 9 September 2019, https://www.tampabay.com/opinion/letters/2019/09/09/era-wouldnt-be-good-for-women-tuesdays-letters/.

Prasad, Ritu. “Women's Equal Rights Amendment sees first hearing in 36 years.” BBC, 30 April 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-44319712.

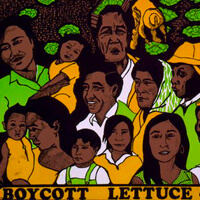

Boycott Lettuce & Grapes Poster (1978)Boycott Lettuce & Grapes (1978)Dolores Huerta Lettuce Boycott Poster: Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez fought together for the rights and protections of the workers who picked fruits and vegetables in the fields and orchards, organizing a workers’ union and boycotts to gain attention and create economic pressure for the cause. Huerta led a successful lettuce and grape boycott, first in California and later on a national scale, that paved the way for migrant labor protection laws.

CitePrintShare(1978) Boycott Lettuce & Grapes. United States, 1978. [Chicago: Women's Graphics Collective] [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/93505187/.

Lily Chin Holds a Photograph of Her Son Vincent Chin (1983)As explained by the New York Times, “Vincent Chin, a Chinese American man who lived near Detroit, was beaten to death with a baseball bat after being pursued by two white autoworkers in 1982…Mr. Chin was killed at a time when the rise of Japanese carmakers and the collapse of Detroit’s auto industry had contributed to a rise in anti-Asian racism.” The two men who murdered Chin accepted plea deals, serving only probation and paying about $3000 each in fines. In this image, Chin’s mother, Lily Chin, holds a photograph of her son.

CitePrintShareSmith, Mitch. “Decades After Infamous Beating Death, Recent Attacks Haunt Asian Americans.” The New York Times, 17 June 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/16/us/vincent-chin-anti-asian-attack-detroit.html.

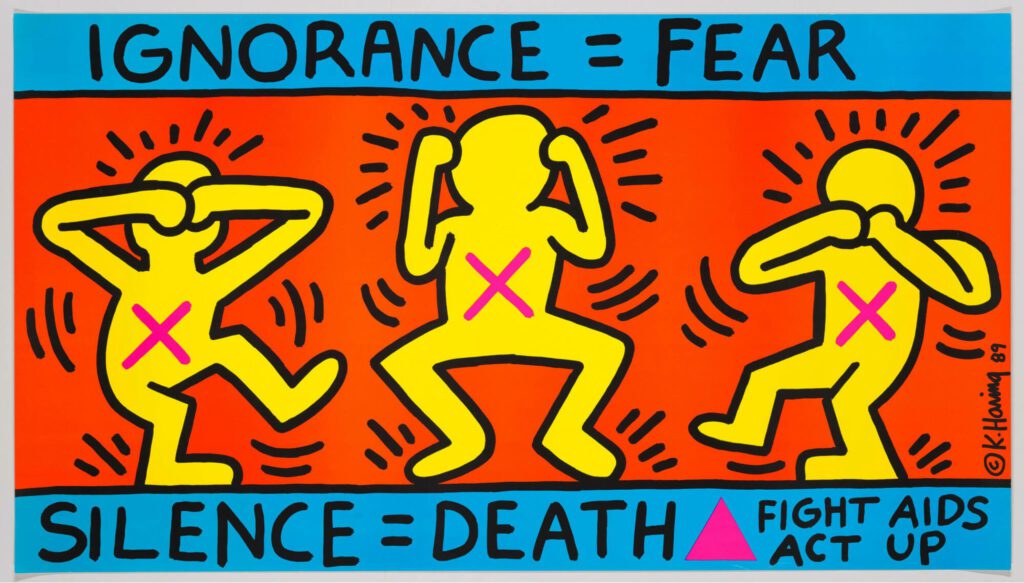

Keith Haring, Ignorance = Fear / Silence = Death (1989)Keith Haring, Ignorance = Fear / Silence = Death (1989)In the earliest years of the emergency of AIDS as a public health crisis, the American Government’s response was limited in terms of both resources dedicated to fighting the disease and public discussion of the disease, its victims, and public health strategies for prevention. Activists coined the phrase “silence=death” in 1987 to help raise awareness and spur the government to devote greater resources and attention.

CitePrintShareSherwin, Skye. “Keith Haring’s Ignorance = Fear: political activism | Art and design.” The Guardian, 23 August 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/aug/23/keith-haring-ignorance-equals-fear.

Tea Party Protests (2009)Tea Party protest at the Connecticut State Capitol in Hartford, Connecticut. April 15, 2009. Organizers reported that the police estimate of attendance was 5000 people.Protesters in Washington D.C. during a rally, September 2009.After the financial crisis of 2008, a CNBC commentator, Rick Santelli, argued against President Obama’s mortgage relief policies and evoked the Revolutionary War-era Tea Party in calling for a protest against them. The “Tea Party Movement” took hold among some conservative and libertarian circles, leading to rallies and political campaigns arguing against federal taxation and in favor of fiscal conservatism and a free market economy. Several rallies were held specifically on April 15th – Tax Day – 2009.

CitePrintShareRoss, Sage. “File:Tea Party Protest, Hartford, Connecticut, 15 April 2009 - 041.jpg.” Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tea_Party_Protest,_Hartford,_Connecticut,_15_April_2009_-_041.jpg.

Zeleny, Jeff. “In Washington, Thousands Stage Protest of Big Government.” The New York Times, 12 September 2009, https://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/13/us/politics/13protestweb.html.

Occupy Wall Street / Park Avenue Millionaires Protest (2011)Occupy Wall Street Protests Starting in Washington, then moving to New York, protesters camped out in Zucotti park for an extended period of time in 2011 while voicing their concern about inequality in America. The protesters had a unique style of protesting employing methods such as “the people’s mic,” organized childcare, a library, and were predominantly “leaderless.” They had regularly scheduled marches throughout New York City for a variety of issues. Some critique focused on how participants were mostly white, accused of antisemitism, and had an amorphous set of demands.

CitePrintShareWires, N. P. R. S. and. (2011, October 15). Occupy Wall Street inspires worldwide protests. NPR. Retrieved February 27, 2022, from https://www.npr.org/2011/10/15/141382468/occupy-wall-street-inspires-worldwide-protests

Kastenbaum, Steve. “Occupy Wall Street: An experiment in consensus-building.” CNN, 18 October 2011, https://www.cnn.com/2011/10/18/us/occupy-wall-street-consensus-building/index.html.

Rally in Support of DACA (2017)In September of 2017, Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ announcement that the Trump Administration planned to end DACA, or the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, was met with protests around the country. As reported by National Public Radio, “hundreds of demonstrators gathered outside the White House. They shouted ‘We are America’ and ‘We want education. Down with deportation.’ The marchers then proceeded to the Department of Justice…and to the Trump International Hotel on Pennsylvania Avenue, where they staged a sit-in.”

CitePrintShareNeuman, Scott. “Protesters In D.C., Denver, LA, Elsewhere Demonstrate Against Rescinding DACA.” NPR, 5 September 2017, https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/09/05/548727220/protests-in-d-c-denver-la-elsewhere-protest-rescinding-daca.

Dakota Access Pipeline Protest (2017)Dakota Access Pipeline Protests (2017)The planned construction of The Dakota Access Pipeline and resulting protests is a recent example of Native Americans and U.S. industry clashing. One side feared for the quality of their water and lands being abused. Proponents of the pipeline included union members and business, who viewed the pipeline’s development as essential to the growth of the economy.

CitePrintShareHersher, R. (2017, February 22). Key moments in the Dakota Access Pipeline Fight. NPR. Retrieved February 27, 2022, from https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/02/22/514988040/key-moments-in-the-dakota-access-pipeline-fight

Iowa Public Radio | By Amy Mayer. (2020, August 28). Public Voices Support and oppose Bakken pipeline across Iowa. Iowa Public Radio. Retrieved February 26, 2022, from https://www.iowapublicradio.org/environment/2015-11-12/public-voices-support-and-oppose-bakken-pipeline-across-iowa#stream/0

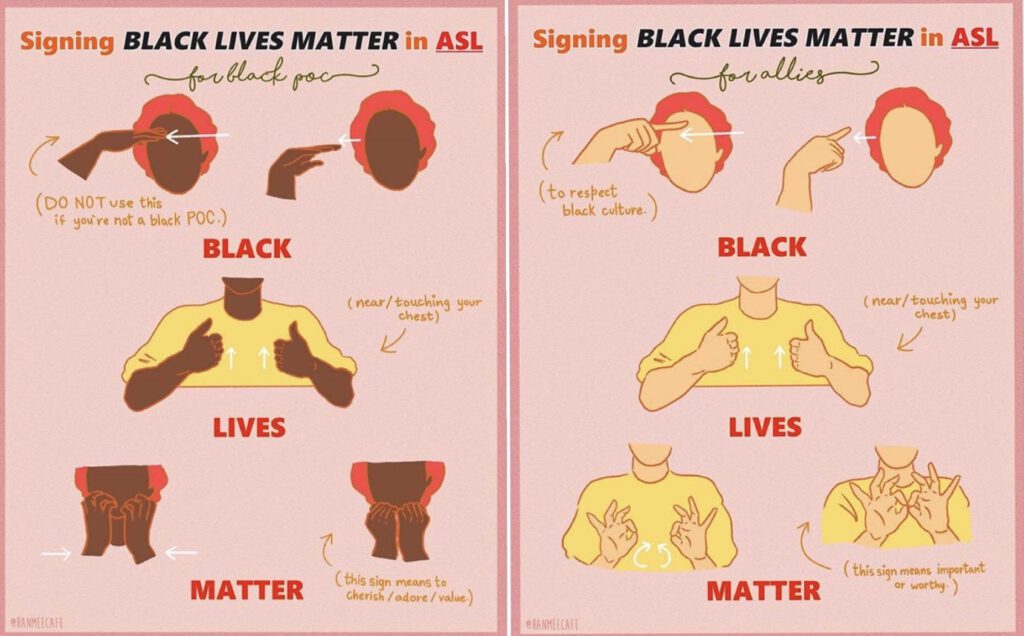

How do you sign ‘Black Lives Matter’ in ASL? (2020)How do you sign ‘Black Lives Matter’ in ASL? (2020)As reported by the Los Angeles Times, the intersection of disability rights and racial equity can be complicated for deaf members of the Black Lives Matter Movement: “The phrase begins with four fingers cut across the brow, followed by two thumbs drawn up like breath from navel to chest, ending with a fierce tug with two hands down from the chin into fists toward the heart.

Black. Life. Cherish. This is how Harold Foxx and many other black deaf Angelenos sign ‘Black Lives Matter,’ though it is by no means a universal translation. .. It is a reminder of an ongoing struggle for equity, representation and authenticity in ASL, a language deeply scarred by racism and exclusion.”

CitePrintShareSharp, Sonja. “Column One: How do you sign 'Black Lives Matter' in ASL? For black deaf Angelenos, it's complicated.” Los Angeles Times, 8 June 2020, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-06-08/how-do-you-sign-black-lives-matter-in-asl-for-black-deaf-angelenos-its-complicated.

Black Lives Matter Plaza (2020)Black Lives Matter Plaza (2020)On June 5, 2020, CNN reported: “Washington, DC is painting a message in giant, yellow letters down a busy DC street ahead of a planned protest this weekend: BLACK LIVES MATTER.

The massive banner-like project spans two blocks of 16th Street, a central axis that leads southward straight to the White House. Each of the 16 bold yellow letters spans the width of the two-lane street, creating an unmistakable visual easily spotted by aerial cameras and virtually anyone within a few blocks. The painters were contacted by Mayor Muriel Bowser and began work early Friday morning, the mayor’s office told CNN. Bowser has officially deemed the section of 16th Street bearing the mural ‘Black Lives Matter Plaza,’ complete with a new street sign.”

CitePrintShareSource of text: Willingham, AJ. “Washington, DC paints a giant 'Black Lives Matter' message on the road to the White House.” CNN, 5 June 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/06/05/us/black-lives-matter-dc-street-white-house-trnd/index.html.

Source of photo: “DC paints huge Black Lives Matter mural near White House.” WCTV, 5 June 2020, https://www.kktv.com/content/news/DC-paints-huge-Black-Lives-Matter-mural-near-White-House-571049311.html.

Protests against Mask Mandates (2021)People demonstrate against mask mandates at a Cobb county, Georgia, school board meeting last week. Photograph: Robin Rayne/Zuma Press Wire/Rex/Shutterstock (2021)Families protest any potential mask mandates before the Hillsborough County School Board meeting last month in Tampa, Fla.During the height of the Coronavirus pandemic, all levels of government – federal, state, and local – were required to respond to information emerging daily about what policies and practices would be safest for the public. In many places, including public spaces and schools, people were required to wear masks. Some people pushed back against these requirements, arguing that mandates were a violation of their individual rights.

CitePrintShareWong, Julia Carrie. “Masks off: how US school boards became 'perfect battlegrounds' for vicious culture wars.” The Guardian, 24 August 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/aug/24/mask-mandates-covid-school-boards.

Shivaram, Deepa. “'Mask Wars' Are Erupting In Schools As Students Return : Back To School: Live Updates.” NPR, 20 August 2021, https://www.npr.org/sections/back-to-school-live-updates/2021/08/20/1028841279/mask-mandates-school-protests-teachers.

Rally against CRT in Schools (2021)Capitol rally to “stop critical race theory in Pennsylvania schools.” Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, July 14, 2021. Dan GleiterWhile “Critical Race Theory” (CRT) is taught primarily in law schools, protests began in 2021 against the teaching of CRT at local school board meetings in many places across the country. Often, participants in these protests raised a range of concerns about how topics including, but not limited to, race are covered in school curricula. These protests became part of a larger “parents’ rights” movement, arguing that parents should have a greater say in determining what their children learn in school.

CitePrintShareDeJesus, Ivey. “Critical race theory: What it is, what it isn't, and what it means for education in Pennsylvania.” Penn Live, 15 July 2021, https://www.pennlive.com/news/2021/07/critical-race-theory-the-nationwide-debate-is-emerging-in-pennsylvania.html.

“I Still Believe in Our City” Public Art (2021)The “I Still Believe In Our City” public art series was created in partnership with the New York City Commission on Human Rights. Courtesy Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya"I Am Not Your Scapegoat" poster.Courtesy Amanda PhingbodhipakkiyaAs reported by NBC News, “Last winter, as violent attacks against Asian elders began to spike, vividly painted portraits of Asian, Pacific Islander and Black people — flanked by vibrant florals and messages like ‘I am not your scapegoat’ — appeared on the walls of New York City's busiest subway and bus stops. Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya’s I Still Believe In Our City public art series, created in partnership with the New York City Commission on Human Rights, reminded millions of commuters of the humanity, diversity and beauty of Asian Americans at a time when many saw them as mere carriers of a deadly virus.”

CitePrintShareWang, Claire. “'I am not your scapegoat': See the art created by Asian Americans in a year of anti-Asian hate.” NBC News, 27 December 2021, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/-not-scapegoat-see-art-created-asian-americans-year-anti-asian-hate-rcna9058.

March against Florida House Bill 1557 (2022)Demonstrators headed toward a pier in St. Petersburg during a rally against the bill.As reported by the New York Times in March of 2022, Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida signed House Bill 1557, “which supporters call the ‘Parental Rights in Education’ bill, but that opponents refer to as the ‘Don’t Say Gay’ bill.” Among the provisions of the bill, “Instruction on gender and sexuality would be constrained in all grades; schools would be required to notify parents when children receive mental, emotional or physical health services, unless educators believe there is a risk of ‘abuse, abandonment, or neglect’; and parents would have the right to opt their children out of counseling and health services.”

CitePrintShareGoldstein, Dana. “What’s in House Bill 1557, Which Opponents Call ‘Don’t Say Gay.’” The New York Times, 18 March 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/18/us/dont-say-gay-bill-florida.html.

Education for American Democracy

As a highly-structured model for conversation, Deliberations allow teachers to help students cooperatively discuss contested political issues by carefully considering multiple perspectives and searching for consensus. This Deliberation focuses on banning hate speech.

The Roadmap

Street Law Inc.

As a highly-structured model for conversation, Deliberations allow teachers to help students cooperatively discuss contested political issues by carefully considering multiple perspectives and searching for consensus. This Deliberation focuses on whether juveniles should be punished as adults.

The Roadmap

Street Law Inc.

As a highly-structured model for conversation, Deliberations allow teachers to help students cooperatively discuss contested political issues by carefully considering multiple perspectives and searching for consensus. This Deliberation focuses on the Electoral College.

The Roadmap

Street Law Inc.

This lesson plan centers on activity wherein students consider Lincoln's 1864 election in a modern context. It includes a debate activity and other exercises guided by substantive questions.

The Roadmap

Annenberg Classroom

Debates are one of the most anticipated events in the lead up to a presidential election. Each candidate carefully plans their strategies to persuade the American public that they are the one to vote for in November. Examine historical examples of presidential debates and customize your own viewing scorecard.

The Roadmap

Smithsonian National Museum of American History

This annotated inquiry leads students through an investigation of a public policy debate by studying the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The compelling question—“Why is the Affordable Care Act so controversial?”—calls out the persistent debate around this legislation and asks students to grapple with the roots of disagreement through the examination of the origins, opportunities, shortcomings, and constitutionality of the ACA.

The Roadmap

C3 Teachers

Download the Roadmap and Report

Download the Educating for American Democracy Roadmap and Report Documents

Get the Roadmap and Report to unlock the work of over 300 leading scholars, educators, practitioners, and others who spent thousands of hours preparing this robust framework and guiding principles. The time is now to prioritize history and civics.

Your contact information will not be shared, and only used to send additional updates and materials from Educating for American Democracy, from which you can unsubscribe.

We the People

This theme explores the idea of “the people” as a political concept–not just a group of people who share a landscape but a group of people who share political ideals and institutions.

Institutional & Social Transformation

This theme explores how social arrangements and conflicts have combined with political institutions to shape American life from the earliest colonial period to the present, investigates which moments of change have most defined the country, and builds understanding of how American political institutions and society changes.

Contemporary Debates & Possibilities

This theme explores the contemporary terrain of civic participation and civic agency, investigating how historical narratives shape current political arguments, how values and information shape policy arguments, and how the American people continues to renew or remake itself in pursuit of fulfillment of the promise of constitutional democracy.

Civic Participation

This theme explores the relationship between self-government and civic participation, drawing on the discipline of history to explore how citizens’ active engagement has mattered for American society and on the discipline of civics to explore the principles, values, habits, and skills that support productive engagement in a healthy, resilient constitutional democracy. This theme focuses attention on the overarching goal of engaging young people as civic participants and preparing them to assume that role successfully.

Our Changing landscapes

This theme begins from the recognition that American civic experience is tied to a particular place, and explores the history of how the United States has come to develop the physical and geographical shape it has, the complex experiences of harm and benefit which that history has delivered to different portions of the American population, and the civics questions of how political communities form in the first place, become connected to specific places, and develop membership rules. The theme also takes up the question of our contemporary responsibility to the natural world.

A New Government & Constitution

This theme explores the institutional history of the United States as well as the theoretical underpinnings of constitutional design.

A People in the World

This theme explores the place of the U.S. and the American people in a global context, investigating key historical events in international affairs,and building understanding of the principles, values, and laws at stake in debates about America’s role in the world.

The Seven Themes

The Seven Themes provide the organizational framework for the Roadmap. They map out the knowledge, skills, and dispositions that students should be able to explore in order to be engaged in informed, authentic, and healthy civic participation. Importantly, they are neither standards nor curriculum, but rather a starting point for the design of standards, curricula, resources, and lessons.

Driving questions provide a glimpse into the types of inquiries that teachers can write and develop in support of in-depth civic learning. Think of them as a starting point in your curricular design.

Learn more about inquiry-based learning in the Pedagogy Companion.

Sample guiding questions are designed to foster classroom discussion, and can be starting points for one or multiple lessons. It is important to note that the sample guiding questions provided in the Roadmap are NOT an exhaustive list of questions. There are many other great topics and questions that can be explored.

Learn more about inquiry-based learning in the Pedagogy Companion.

The Seven Themes

The Seven Themes provide the organizational framework for the Roadmap. They map out the knowledge, skills, and dispositions that students should be able to explore in order to be engaged in informed, authentic, and healthy civic participation. Importantly, they are neither standards nor curriculum, but rather a starting point for the design of standards, curricula, resources, and lessons.

The Five Design Challenges

America’s constitutional politics are rife with tensions and complexities. Our Design Challenges, which are arranged alongside our Themes, identify and clarify the most significant tensions that writers of standards, curricula, texts, lessons, and assessments will grapple with. In proactively recognizing and acknowledging these challenges, educators will help students better understand the complicated issues that arise in American history and civics.

Motivating Agency, Sustaining the Republic

- How can we help students understand the full context for their roles as civic participants without creating paralysis or a sense of the insignificance of their own agency in relation to the magnitude of our society, the globe, and shared challenges?

- How can we help students become engaged citizens who also sustain civil disagreement, civic friendship, and thus American constitutional democracy?

- How can we help students pursue civic action that is authentic, responsible, and informed?

America’s Plural Yet Shared Story

- How can we integrate the perspectives of Americans from all different backgrounds when narrating a history of the U.S. and explicating the content of the philosophical foundations of American constitutional democracy?

- How can we do so consistently across all historical periods and conceptual content?

- How can this more plural and more complete story of our history and foundations also be a common story, the shared inheritance of all Americans?

Simultaneously Celebrating & Critiquing Compromise

- How do we simultaneously teach the value and the danger of compromise for a free, diverse, and self-governing people?

- How do we help students make sense of the paradox that Americans continuously disagree about the ideal shape of self-government but also agree to preserve shared institutions?

Civic Honesty, Reflective Patriotism

- How can we offer an account of U.S. constitutional democracy that is simultaneously honest about the wrongs of the past without falling into cynicism, and appreciative of the founding of the United States without tipping into adulation?

Balancing the Concrete & the Abstract

- How can we support instructors in helping students move between concrete, narrative, and chronological learning and thematic and abstract or conceptual learning?

Each theme is supported by key concepts that map out the knowledge, skills, and dispositions students should be able to explore in order to be engaged in informed, authentic, and healthy civic participation. They are vertically spiraled and developed to apply to K—5 and 6—12. Importantly, they are not standards, but rather offer a vision for the integration of history and civics throughout grades K—12.

Helping Students Participate

- How can I learn to understand my role as a citizen even if I’m not old enough to take part in government? How can I get excited to solve challenges that seem too big to fix?

- How can I learn how to work together with people whose opinions are different from my own?

- How can I be inspired to want to take civic actions on my own?

America’s Shared Story

- How can I learn about the role of my culture and other cultures in American history?

- How can I see that America’s story is shared by all?

Thinking About Compromise

- How can teachers teach the good and bad sides of compromise?

- How can I make sense of Americans who believe in one government but disagree about what it should do?

Honest Patriotism

- How can I learn an honest story about America that admits failure and celebrates praise?

Balancing Time & Theme

- How can teachers help me connect historical events over time and themes?

The Six Pedagogical Principles

EAD teacher draws on six pedagogical principles that are connected sequentially.

Six Core Pedagogical Principles are part of our Pedagogy Companion. The Pedagogical Principles are designed to focus educators’ effort on techniques that best support the learning and development of student agency required of history and civic education.

EAD teachers commit to learn about and teach full and multifaceted historical and civic narratives. They appreciate student diversity and assume all students’ capacity for learning complex and rigorous content. EAD teachers focus on inclusion and equity in both content and approach as they spiral instruction across grade bands, increasing complexity and depth about relevant history and contemporary issues.

Growth Mindset and Capacity Building

EAD teachers have a growth mindset for themselves and their students, meaning that they engage in continuous self-reflection and cultivate self-knowledge. They learn and adopt content as well as practices that help all learners of diverse backgrounds reach excellence. EAD teachers need continuous and rigorous professional development (PD) and access to professional learning communities (PLCs) that offer peer support and mentoring opportunities, especially about content, pedagogical approaches, and instruction-embedded assessments.

Building an EAD-Ready Classroom and School

EAD teachers cultivate and sustain a learning environment by partnering with administrators, students, and families to conduct deep inquiry about the multifaceted stories of American constitutional democracy. They set expectations that all students know they belong and contribute to the classroom community. Students establish ownership and responsibility for their learning through mutual respect and an inclusive culture that enables students to engage courageously in rigorous discussion.

Inquiry as the Primary Mode for Learning

EAD teachers not only use the EAD Roadmap inquiry prompts as entry points to teaching full and complex content, but also cultivate students’ capacity to develop their own deep and critical inquiries about American history, civic life, and their identities and communities. They embrace these rigorous inquiries as a way to advance students’ historical and civic knowledge, and to connect that knowledge to themselves and their communities. They also help students cultivate empathy across differences and inquisitiveness to ask difficult questions, which are core to historical understanding and constructive civic participation.

Practice of Constitutional Democracy and Student Agency

EAD teachers use their content knowledge and classroom leadership to model our constitutional principle of “We the People” through democratic practices and promoting civic responsibilities, civil rights, and civic friendship in their classrooms. EAD teachers deepen students’ grasp of content and concepts by creating student opportunities to engage with real-world events and problem-solving about issues in their communities by taking informed action to create a more perfect union.

Assess, Reflect, and Improve

EAD teachers use assessments as a tool to ensure all students understand civics content and concepts and apply civics skills and agency. Students have the opportunity to reflect on their learning and give feedback to their teachers in higher-order thinking exercises that enhance as well as measure learning. EAD teachers analyze and utilize feedback and assessment for self-reflection and improving instruction.

EAD teachers commit to learn about and teach full and multifaceted historical and civic narratives. They appreciate student diversity and assume all students’ capacity for learning complex and rigorous content. EAD teachers focus on inclusion and equity in both content and approach as they spiral instruction across grade bands, increasing complexity and depth about relevant history and contemporary issues.

Growth Mindset and Capacity Building

EAD teachers have a growth mindset for themselves and their students, meaning that they engage in continuous self-reflection and cultivate self-knowledge. They learn and adopt content as well as practices that help all learners of diverse backgrounds reach excellence. EAD teachers need continuous and rigorous professional development (PD) and access to professional learning communities (PLCs) that offer peer support and mentoring opportunities, especially about content, pedagogical approaches, and instruction-embedded assessments.

Building an EAD-Ready Classroom and School

EAD teachers cultivate and sustain a learning environment by partnering with administrators, students, and families to conduct deep inquiry about the multifaceted stories of American constitutional democracy. They set expectations that all students know they belong and contribute to the classroom community. Students establish ownership and responsibility for their learning through mutual respect and an inclusive culture that enables students to engage courageously in rigorous discussion.

Inquiry as the Primary Mode for Learning

EAD teachers not only use the EAD Roadmap inquiry prompts as entry points to teaching full and complex content, but also cultivate students’ capacity to develop their own deep and critical inquiries about American history, civic life, and their identities and communities. They embrace these rigorous inquiries as a way to advance students’ historical and civic knowledge, and to connect that knowledge to themselves and their communities. They also help students cultivate empathy across differences and inquisitiveness to ask difficult questions, which are core to historical understanding and constructive civic participation.

Practice of Constitutional Democracy and Student Agency

EAD teachers use their content knowledge and classroom leadership to model our constitutional principle of “We the People” through democratic practices and promoting civic responsibilities, civil rights, and civic friendship in their classrooms. EAD teachers deepen students’ grasp of content and concepts by creating student opportunities to engage with real-world events and problem-solving about issues in their communities by taking informed action to create a more perfect union.

Assess, Reflect, and Improve

EAD teachers use assessments as a tool to ensure all students understand civics content and concepts and apply civics skills and agency. Students have the opportunity to reflect on their learning and give feedback to their teachers in higher-order thinking exercises that enhance as well as measure learning. EAD teachers analyze and utilize feedback and assessment for self-reflection and improving instruction.