The curated resources linked below are an initial sample of the resources coming from a collaborative and rigorous review process with the EAD Content Curation Task Force.

Reset All

Reset All

The phrase “a house divided” comes from Abraham Lincoln’s speech to the Illinois Republican State Convention in 1858, when he describes a nation so badly torn between those that permitted slavery and those that prohibited it that it was on the brink of war. While the issue of slavery is understood to be central to the start of the Civil War, this set of resources is intended to introduce students to more details of the growing tension in the nation. Resources include information and images about expanding territory and the addition of new states to the union; voices of the abolitionist movement; political tension and acts of violence. It does not provide comprehensive coverage of these decades, but it helps to highlight that the growing tension was both multifaceted and happening across the entire nation.

The resources in this spotlight kit are intended for classroom use, and are shared here under a CC-BY-SA license. Teachers, please review the copyright and fair use guidelines.

The Roadmap

- Primary Resources by Decade1830s (4)1840s (3)1850s (9)

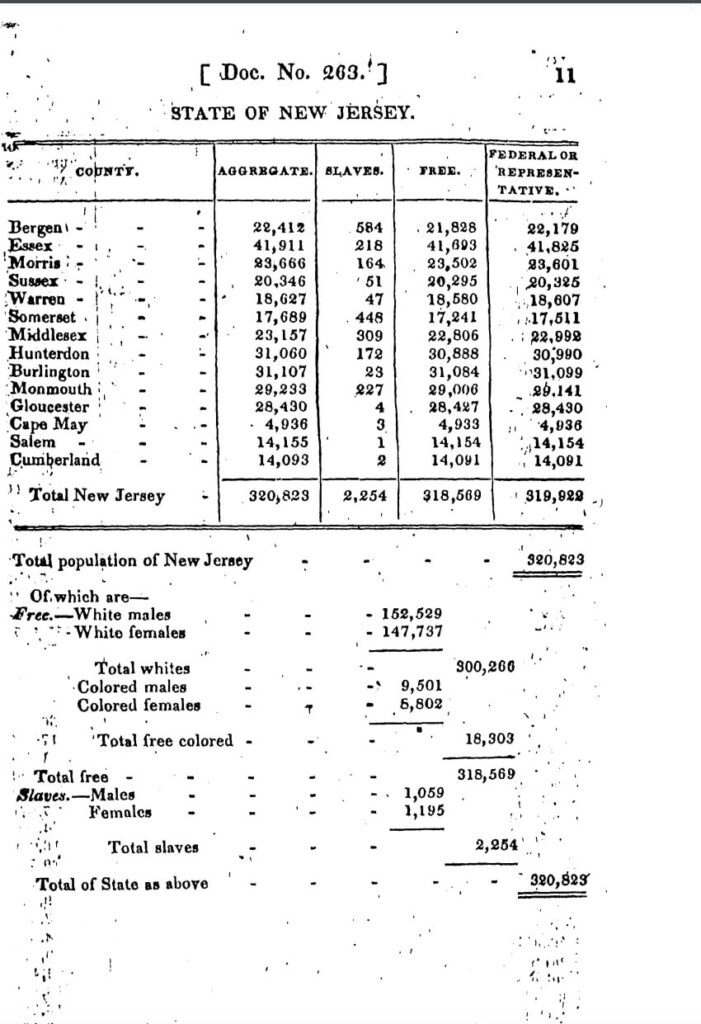

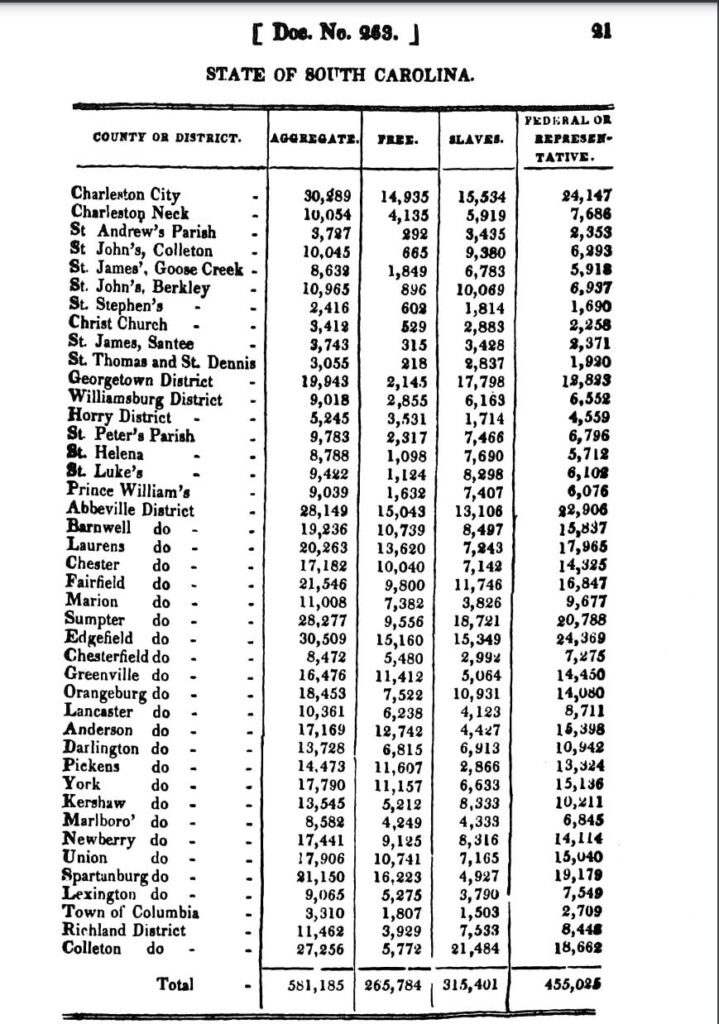

- All 16 Primary ResourcesThe Census of 1830

This abstract of the Census from 1830 not only provides numbers, state by state, of free and enslaved persons – but students will note that there are enslaved persons in many of the states they consider “free” (sample pages at left).

Note that the terminology is historically accurate but might be offensive to students unless context is provided (this will be true for many of the documents from this era).

CitePrintSharehttps://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1830/1830b.pdf

ORIIN, DUFF. “1830 Census - Full Document.” Census.gov, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1830/1830b.pdf.

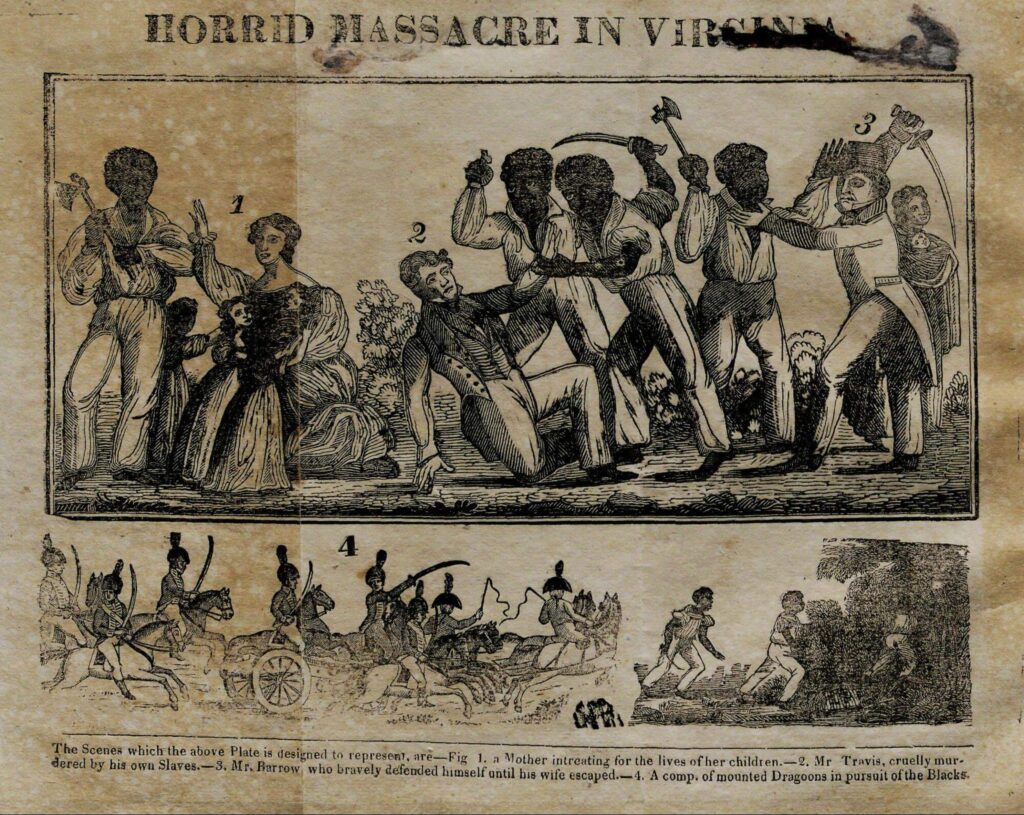

Nat Turner’s Rebellion, 1831Transcript“Even though Turner and his followers had been stopped, panic spread across the region. In the days following the attack, 3000 soldiers, militia men, and vigilantes killed more than one hundred suspected rebels. …Nat Turner’s rebellion led to the passage of a series of new laws. The Virginia legislature actually debated ending slavery, but chose instead to impose additional restrictions and harsher penalties on the activities of both enslaved and free African Americans. Other slave states followed suit, restricting the rights of free and enslaved blacks to gather in groups, travel, preach, and learn to read and write.” (Gilder Lehrman, link at right.)

Nat Turner’s Rebellion led to both public debate and a tightening of laws and policies. “Nat Turner was an enslaved man who had learned to read and write and become a religious leader despite his enslavement; following what he took to be religious signs, he led other enslaved people in an armed uprising. The violence of the uprising and Turner’s ability to escape and hide for approximately six weeks following the event led to changes in laws and policies and also led to a widespread climate of fear among white slaveholders. Enslaved people in far-flung states who had no connection to the event were lynched by white mobs. The State of Virginia briefly considered ending the practice of slavery in the wake of the rebellion, but they ultimately decided instead to tighten the laws of slavery.

1Africans in America/Part 3/Nat Turner's Rebellion. (n.d.). PBS. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part3/3p1518.html and Nat Turner - Rebellion, Death & Facts - HISTORY. (2021, January 26). History.com. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/nat-turnerCitePrintShareAllyn, Nelson. “Nat Turner's Rebellion, 1831 | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.” Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History |, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/nat-turner%E2%80%99s-rebellion-1831.

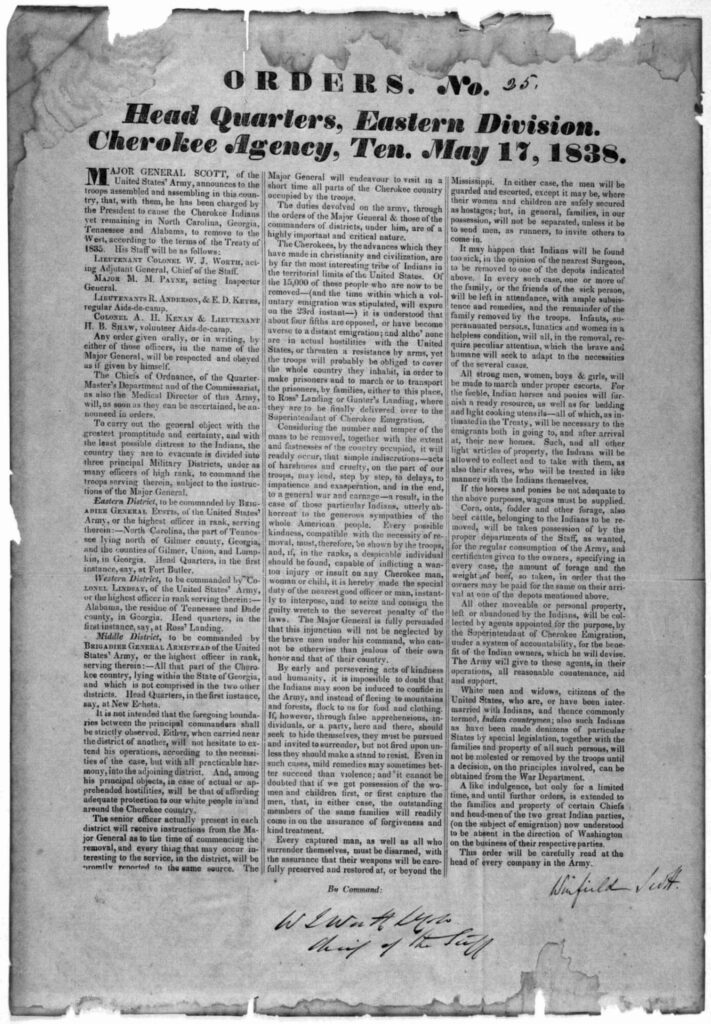

Orders pursuant to the Indian Removal Act of 1830 (Trail of Tears)Orders pursuant to the Indian Removal Act of 1830 (Trail of Tears)While the Trail of Tears and “Indian Removal Act” are not central to understanding slavery, they are critical events in the history of the country in this era; in addition, the concept of “indian removal” connects directly to tensions that rose as the nation expanded in both population and territory.

As the United States acquired Western territories, and as the power battle between slaveholding and free states continued, the land on which Native nations lived became increasingly valuable. After President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Choctaw, Creek, and Cherokee nations were forced to move from their land, most often on foot and with the deaths of many people, into Western territories. The 1838 forced removal of the Cherokee people from their Georgia land led to the deaths of thousands of people (exact numbers are unknown, but estimates range around 4,000 - 5,000.)

1- History & Culture - Trail Of Tears National Historic Trail (US National Park Service). (2020, July 10). National Park Service. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/trte/learn/historyculture/index.htm and Trail of Tears: Indian Removal Act, Facts & Significance - HISTORY. (2020, July 7). History.com. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.history.com/topics/native-american-history/trail-of-tears

CitePrintShare“Tile.loc.gov.” Library of Congress, https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/rbc/rbpe/rbpe17/rbpe174/1740400a/1740400a.pdf.

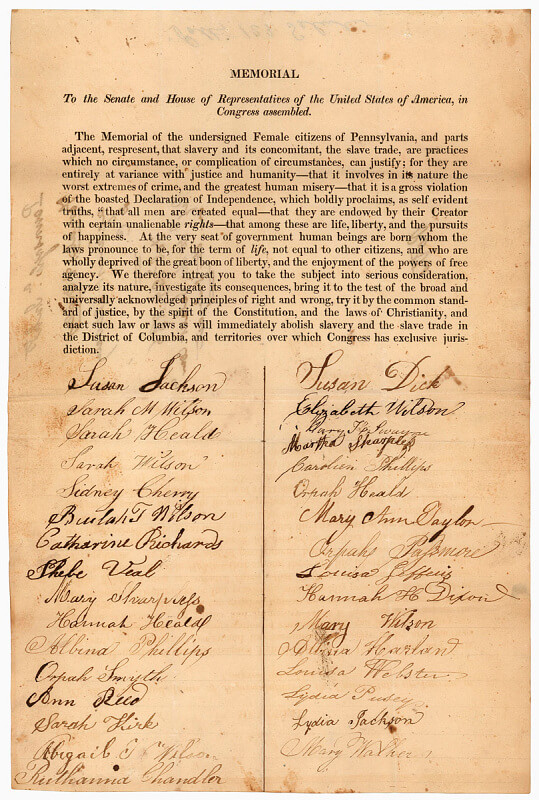

The Gag Rule, 1836“On May 26, 1836, the House of Representatives adopted a ‘Gag Rule’ stating that all petitions regarding slavery would be tabled without being read, referred, or printed….The enactment of the Gag Rule, rather than discouraging petitioners, energized the anti-slavery movement to flood the Capitol with written demands. Activists held up the suppression of debate as an example of the slaveholding South’s infringement of the rights of all Americans.”

CitePrintShareAdams, John Quincy. “The Gag Rule | National Museum of American History.” National Museum of American History, https://americanhistory.si.edu/democracy-exhibition/beyond-ballot/petitioning/gag-rule.

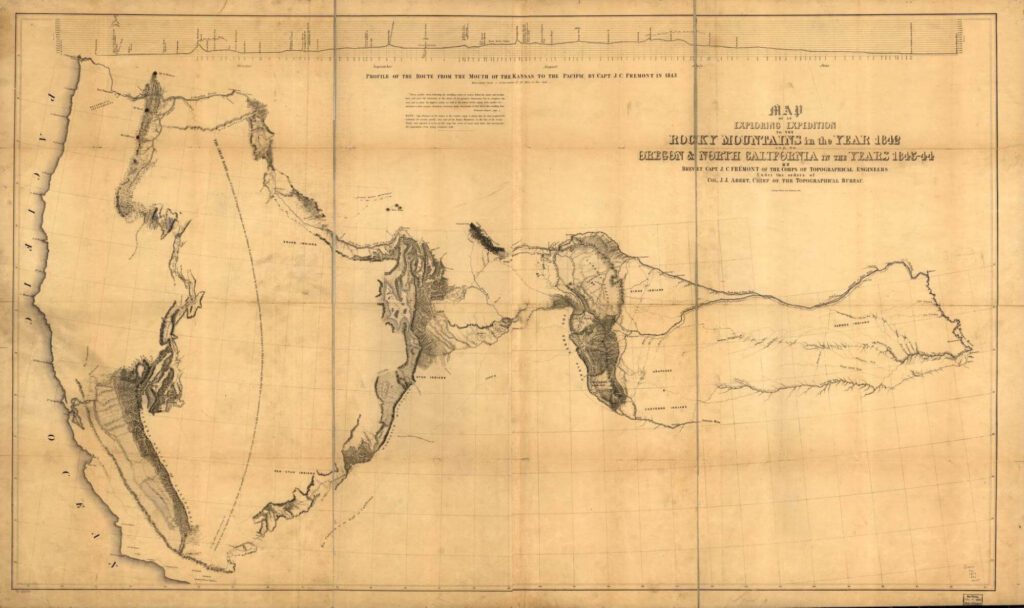

Map of Westward Expedition and Expansion, 1842-44Map of an exploring expedition to the Rocky Mountains in the year 1842 and to Oregon & north California in the years 1843-44As the nation expanded Westward, tensions rose further over whether new states and territories would permit or prohibit slavery.

CitePrintShareMap of an Exploring Expedition to the Rocky ... - Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4051s.ct000909/.

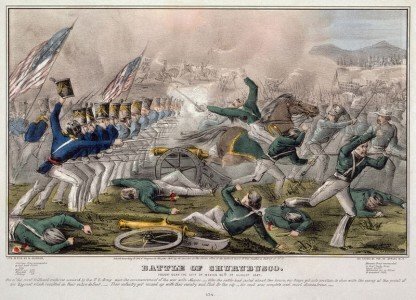

Battlefield Painting, Mexican-American WarBattlefield Painting, Mexican-American War“The pact set a border between Texas and Mexico and ceded California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming to the United States. …the acquisition of so much territory with the issue of slavery unresolved lit the fuse that eventually set off the Civil War in 1861.”

CitePrintShare“The Mexican-American war in a nutshell.” National Constitution Center, 13 May 2021, https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/the-mexican-american-war-in-a-nutshell.

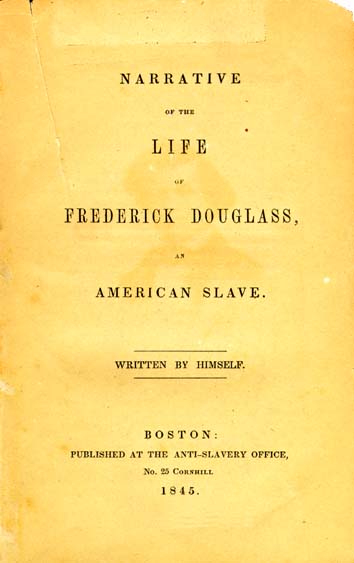

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, excerpt, 1845TranscriptCHAPTER I. I WAS born in Tuckahoe, near Hillsborough, and about twelve miles from Easton, in Talbot county, Maryland. I have no accurate knowledge of my age, never having seen any authentic record containing it. By far the larger part of the slaves know as little of their ages as horses know of theirs, and it is the wish of most masters within my knowledge to keep their slaves thus ignorant. I do not remember to have ever met a slave who could tell of his birthday. They seldom come nearer to it than planting-time, harvest-time, cherry-time, spring-time, or fall-time. A want of information concerning my own was a source of unhappiness to me even during childhood. The white children could tell their ages. I could not tell why I ought to be deprived of the same privilege. I was not allowed to make any inquiries of my master concerning it. He deemed all such inquiries on the part of a slave improper and impertinent, and evidence of a restless spirit. The nearest estimate I can give makes me now between twenty-seven and twenty-eight years of age. I come to this, from hearing my master say, some time during 1835, I was about seventeen years old.

Students would benefit from reading an excerpt of the text of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass – but in addition, the cover itself is an interesting artifact, and students can discuss its details and its possible impact upon publication in 1845. (See also text in this chart, below, from Frederick Douglass’ July 4 address in 1852.)

CitePrintShareHempel, Carlene, et al. “Frederick Douglass, 1818-1895. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Written by Himself.” Documenting the American South, https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/douglass/douglass.html.

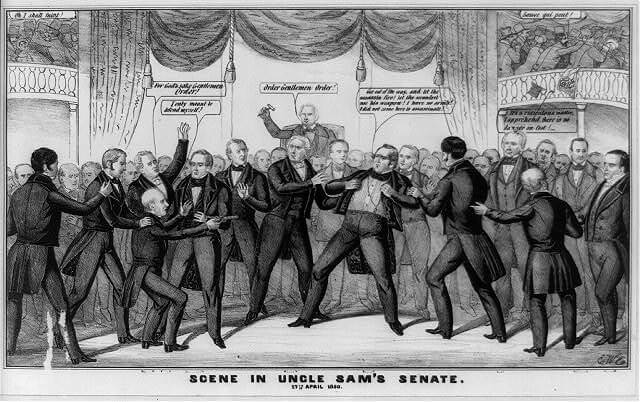

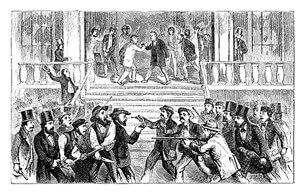

Scene in Uncle Sam’s Senate, 1850“Scene in Uncle Sam's Senate.Transcript"A somewhat tongue-in-cheek dramatization of the moment during the heated debate in the Senate over the admission of California as a free state when Mississippi senator Henry S. Foote drew a pistol on Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri.”

As new states were added to the nation, the question of how many would permit slavery and how many would prohibit it – and, therefore, which faction had more power – continued to contribute to growing tension.

CitePrintShare“Scene in Uncle Sam's Senate. 17th April 1850.” The Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2008661528/.

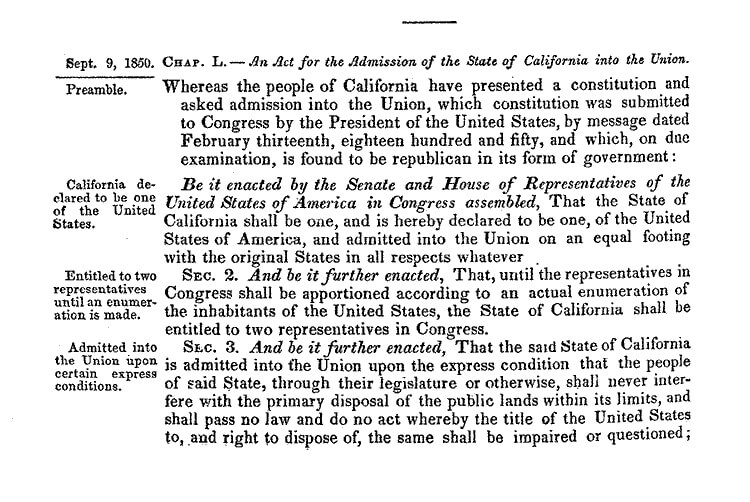

An Act for the Admission of the State of California into the Union, 1850CitePrintShareA Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 - 1875, https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llsl&fileName=009%2Fllsl009.db&recNum=479.

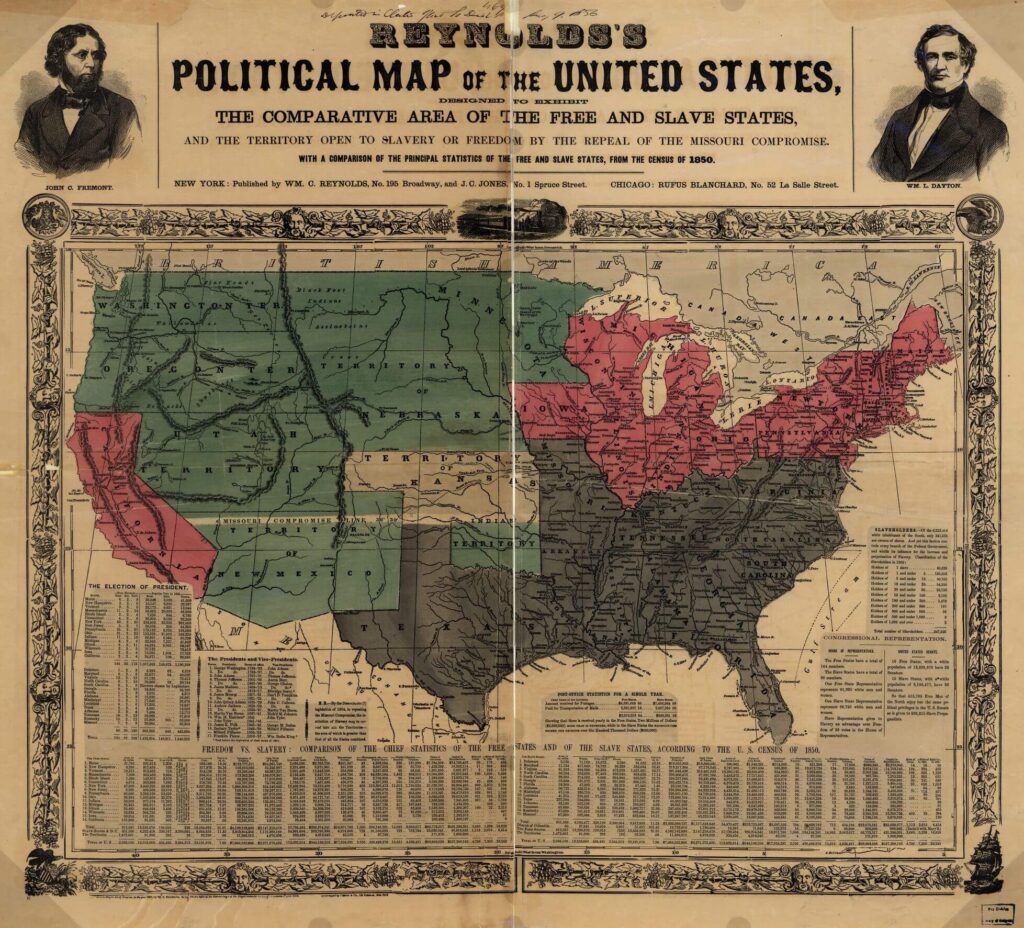

Political Map of the United States in 1850Political map of the United States in 1850This map has a range of valuable information, not only about Presidential politics, but also about population statistics and slavery. It makes a particular point of comparison with the 1830 Census, hyperlinked above in this chart.

CitePrintShare“1850 Political Map of the United States - History.” U.S. Census Bureau, 9 December 2021, https://www.census.gov/history/www/reference/maps/1850_political_map_of_the_united_states.html.

Frederick Douglass, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”, 1852Douglass raises critical questions about patriotism, citizenship, and the nation’s ideals in this address. The text highlights issues that will continue to be points of tension not only at the start of the Civil War, but throughout Reconstruction (and, truly, throughout American history).

“I say it with a sad sense of the disparity between us. I am not included within the pale of glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

- Frederick Douglass, July 5, 1852CitePrintShareJuly 5, 1852, Frederick Douglass keynote address at an Independence Day celebration: “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”

“A Nation's Story: “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”” National Museum of African American History and Culture, 3 July 2018, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/nations-story-what-slave-fourth-july.

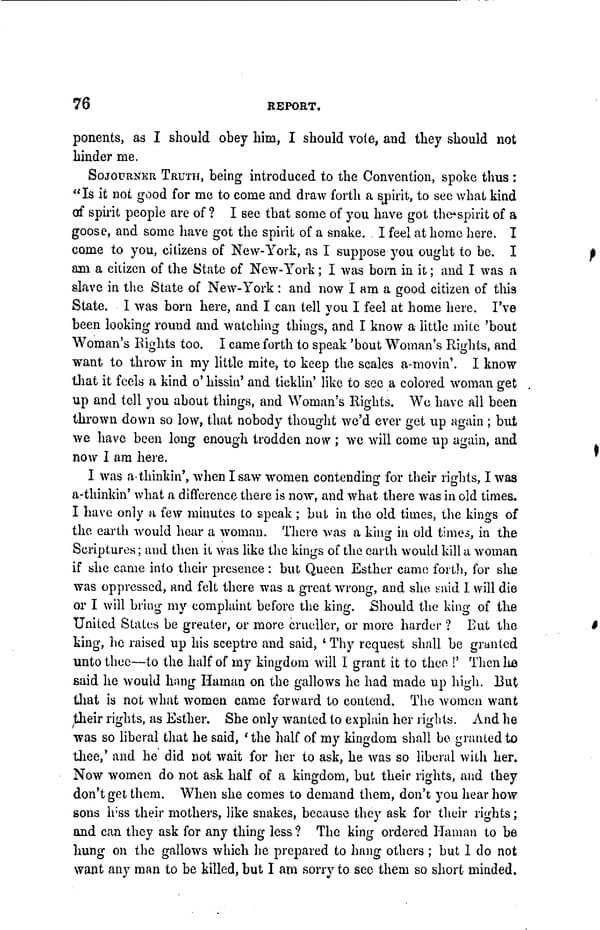

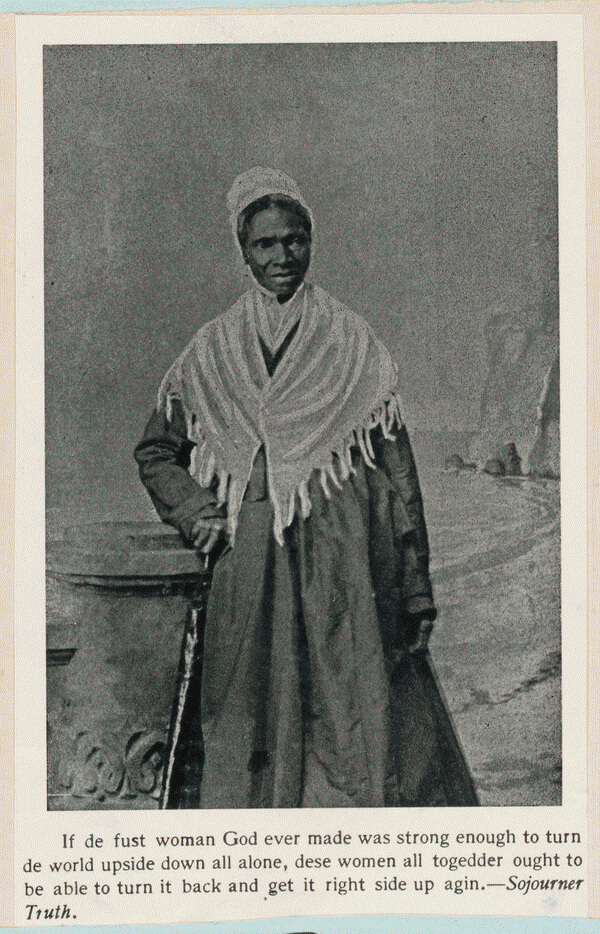

Sojourner Truth, Photograph and Speech at the Women’s Rights Convention, 1853See above; understanding the life and words of Sojourner Truth helps students to understand the complexity and intersectionality of both the women’s rights movement and the abolitionist movement.

CitePrintShareTitle Proceedings of the Woman's Rights Convention held at the Broadway Tabernacle, in the city of New York, on Tuesday and Wednesday, Sept. 6th and 7th, 1853.

Summary Sojourner Truth addresses the convention.

Image 76 of Susan B. Anthony Collection Copy | Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbnawsa.n8289/?sp=76.

“Bleeding Kansas,” 1858“The years of 1854-1861 were a turbulent time in Kansas territory. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 …allowed the residents of these territories to decide by popular vote whether their state would be free or slave. This concept of self-determination was called popular sovereignty'. …Three distinct political groups occupied Kansas: pro-slavers, free-staters and abolitionists. Violence broke out immediately between these opposing factions and continued until 1861 when Kansas entered the Union as a free state on January 29th. This era became forever known as ‘Bleeding Kansas’.” (National Park Service, link at right.)

CitePrintShare“Bleeding Kansas - Fort Scott National Historic Site (US National Park Service).” National Park Service, 23 April 2020, https://www.nps.gov/fosc/learn/historyculture/bleeding.htm.

Abraham Lincoln, “A House Divided” Speech, 1858This excerpt from (or the entirety of) Lincoln’s address to the Republican State Convention puts the notion of “a house divided” in its original context, just before the start of the Civil War.

NOTE: Because it provides the central concept of this set of resources, I’ve included it last (although it predates John Brown’s speech above.)

Illinois Republican State Convention, Springfield, Illinois June 16, 1858Abraham Lincoln

Mr. President and Gentlemen of the Convention. If we could first know where we are, and whither we are tending, we could better judge what to do, and how to do it.

We are now far into the fifth year, since a policy was initiated, with the avowed object, and confident promise, of putting an end to slavery agitation. Under the operation of that policy, that agitation has not only, not ceased, but has constantly augmented.

In my opinion, it will not cease, until a crisis shall have been reached, and passed -

"A house divided against itself cannot stand."

I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free.

I do not expect the Union to be dissolved - I do not expect the house to fall - but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other.

1- John Brown's Raid (US National Park Service). (2021, July 30). National Park Service. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/articles/john-browns-raid.htm

- John Brown's Raid on Harper's Ferry. (n.d.). Ohio History Central. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://ohiohistorycentral.org/w/John_Brown%27s_Raid_on_Harper%27s_Ferry

CitePrintShare“House Divided Speech - Lincoln Home National Historic Site (US National Park Service).” National Park Service, 10 April 2015, https://www.nps.gov/liho/learn/historyculture/housedivided.htm.

An excerpt from John Brown's address to the court after hearing his guilty verdict, 1859John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry fits into Lincoln’s foretelling of a crisis and further spurs the start of the Civil War. Brown’s speech to the courtroom highlights his sense of what, in this moment, constitutes justice and injustice.

John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry: John Brown, an abolitionist, led the Raid on Harper’s Ferry, a federal arsenal, in an effort to start an armed insurrection against slavery. The event, which took place after Lincoln’s “a house divided” speech, serves as an example of the violence Lincoln foretold. Brown echoed Lincoln’s sentiments, explaining in 1859, “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed it might be done.” Brown and his followers were trapped and arrested, and Brown was tried and found guilty of treason.

“I have, may it please the court, a few words to say. In the first place, I deny everything but what I have all along admitted--the design on my part to free the slaves. I intended certainly to have made a clean thing of that matter, as I did last winter when I went into Missouri and there took slaves without the snapping of a gun on either side, moved them through the country, and finally left them in Canada. I designed to have done the same thing again on a larger scale. That was all I intended. I never did intend murder, or treason, or the destruction of property, or to excite or incite slaves to rebellion, or to make insurrection.I have another objection; and that is, it is unjust that I should suffer such a penalty. Had I interfered in the manner which I admit...had I so interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great, or in behalf of any of their friends--either father, mother, brother, sister, wife, or children, or any of that class--and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been all right; and every man in this court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment.”

CitePrintShare“An excerpt from John Brown's address to the court after hearing his guilty verdict, 1859.” Digital Public Library of America, https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/john-brown-s-raid-on-harper-s-ferry/sources/1722.

The Women’s Rights Convention of 1853TranscriptQuotation beneath the photograph: "If de fust woman God ever made was strong enough to turn de world upside down all alone, dese women all togedder ought to be able to turn it back and get it right side up agin."

This photograph pairs with the text in the row below from the Women’s Rights Convention of 1853, when Sojourner Truth spoke to the group.

The Women’s Rights Convention: The Seneca Falls Convention of 1848 is a significant event in the fight for women’s rights and for women’s suffrage, though activists at the convention itself debated whether suffrage should be the center point of their platform. In addition, the Seneca Falls Convention is now widely understood to represent some tension between the women’s rights movement and the abolitionist movement; some activists at the time felt that the right to vote should not go to black men before white women. In this collection of documents, Sojourner Truth’s speech to a smaller, subsequent convention – one held in New York in 1853 – is included, largely because of the critical role Sojourner Truth plays in demonstrating the importance of the intersectionality of both the women’s rights and abolitionist movements.

1- On this day, the Seneca Falls Convention begins. (2021, July 19). National Constitution Center. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/on-this-day-the-seneca-falls-convention-begins and More Women's Rights Conventions - Women's Rights National Historical Park (US National Park Service). (n.d.). National Park Service. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/wori/learn/historyculture/more-womens-rights-conventions.htm and Proceedings of the Woman's Rights Convention held at the Broadway Tabernacle, in the city of New York, on Tuesday and Wednesday, Sept. 6th and 7th, 1853. (n.d.). Library of Congress. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.loc.gov/item/93838289/

CitePrintShare“Sojourner Truth.” The Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/rbcmiller001306/.

Education for American Democracy

This resource set contains best practices for teaching about Native people in your classroom and sample maps with Native viewpoints and inquiry questions to use in your classroom.

The Roadmap

Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center

Ths primary source set focuses on material culture produced about and by American Indians. The information and materials in the set can be used as a jumping off point for teachers looking to access resources provided by the Library of Congress related to the topic.

The Roadmap

Emerging America - Collaborative for Educational Services

In the decades following the Civil War, the US military clashed with Native Americans in the West. The Battle of Little Bighorn was one of the Native Americans' most famous victories. In this lesson, students explore causes of the battle by comparing two primary documents with a textbook account.

The Roadmap

Stanford History Education Group

This 12-lesson teacher's guide accompanies the Emmy-award winning documentary film, DAWNLAND, about the forced removal and coerced assimilation of Indigenous children and the first truth and reconciliation commission in U.S. history to focus on issues of importance to Indigenous Peoples. The compelling question of the guide is: What is the relationship between the taking of the land and the taking of the children?

The Roadmap

Upstander Project

This resources engages with the tumultuous start of this countries origin. Drawing on contemporary debates that resulted from the New York Time's 1619 project and the Trump Administration's 1776 Unites project, students will consider the most accurate way to tell the beginning of the United States, with focus on the role of Indigenous removal and enslaved people in its founding.

The Roadmap

New American History

Students explore themes of social justice and fair access through a simulation activity, creating new rules for settlement of a new planet Earth. They debrief the activity using John Rawls's concept of the ‘Veil of Ignorance.’ Students define social justice in terms of fair access and create their own vision of what a just future looks like.

The Roadmap

High Resolves

In this lesson, students will analyze the visual and literary visions of the New World that were created in England during the early phases of colonization, and the impact they had on the development of the patterns of colonization that dominated the early 17th century. This lesson will enable students to interact with written and visual accounts of this critical formative period at the end of the 16th century, when the English view of the New World was being formulated, with consequences that we are still seeing today.

The Roadmap

National Endowment for the Humanities

In this learning resource, students use geospatial technology to understand how Native land changed hands from the start of European colonization to the contemporary moment. Students will understand the impact settler colonialism has on Indigenous people and their homes and the changes of population that resulted from westward expansion.

The Roadmap

Esri

This learning resource looks at the South during the Civil War and after and how migration patterns changed during this time. Students will look at videos, maps, and historical documents to understand the impact of emancipation for Black people in the South and the impact of railroads on the westward expanding country.

The Roadmap

New American History

This learning resources investigates the removal of Indigenous nations in the South East during Andrew Jackson's presidency. Students will analyze the impact of the Trail of Tears on Indigenous people and contemporary issues that Indigenous people face today.

The Roadmap

New American History

As a new country, the United States made alliances with France and made agreements with indigenous nations. George Washington’s Farewell Address laid the foundation for the principles of American foreign policy, which urged leaders to avoid foreign entanglement; however, the United States found itself during the Early Republic engaged in foreign challenges. The 19th Century quickened the pace at which American policy added territory to the country. Indigenous nations, European powers and continental neighbors would all be part of the narrative as expansion influenced much of national policy. The United States proclaimed the Western Hemisphere off limits to European states in the Monroe Doctrine, although it would be decades before it could be effectively upheld.

The end of the 19th century and early 20th century established the fundamental tensions in US policy and how it plays a role in global affairs. The Spanish American War established the nation as a world power but ignited significant debate over that role. The annexation of places like the Philippines appeared incompatible to democratic ideals for many. Others saw adding territories like Hawaii as necessary for trade and military security. World War I led to serious proposals, led by the United States, guaranteeing future peace via collective security. However, Washington’s admonition about “foreign entanglements” proved more popular with the people and the United States embraced isolation and neutrality until World War II.

Over the last 70 years, the United States continues to be influenced by its economic self interest, its political ideals and its historical isolationist stance. Certainly, US foreign policy has been inconsistent as it struggles with the instructions offered by its first president and the demands of the global community.

The resources in this spotlight kit are intended for classroom use, and are shared here under a CC-BY-SA license. Teachers, please review the copyright and fair use guidelines.

The Roadmap

- Primary Resources by Era/DateAmerican Revolution and the Early Republic 1778-1823 (4)Antebellum-World War I (1845-1919) (8)World War II Era (1938-1946) (6)Post-War Era (1951-Present) (5)

- All 23 Primary ResourcesTreaty with the Delaware (1778)Transcript

Articles of agreement and confederation, made and, entered; into by, Andrew and Thomas Lewis, Esquires, Commissioners for, and in Behalf of the United States of North-America of the one Part, and Capt. White Eyes, Capt. John Kill Buck, Junior, and Capt. Pipe, Deputies and Chief Men of the Delaware Nation of the other Part.

ARTICLE I.

That all offenses or acts of hostilities by one, or either of the contracting parties against the other, be mutually forgiven, and buried in the depth of oblivion, never more to be had in remembrance.ARTICLE II.

That a perpetual peace and friendship shall from henceforth take place, and subsist between the contracting: parties aforesaid, through all succeeding generations: and if either of the parties are engaged in a just and necessary war with any other nation or nations, that then each shall assist the other in due proportion to their abilities, till their enemies are brought to reasonable terms of accommodation: and that if either of them shall discover any hostile designs forming against the other, they shall give the earliest notice thereof that timeous measures may be taken to prevent their ill effect.This treaty established a tenuous peace between Americans and Native Americans. As explained in Smithsonian Magazine, “The Treaty with the Delaware Nation, signed at Fort Pitt in September 1778, represents a time when the newly independent United States needed American Indian allies to drive British troops from forts and outposts west of the Appalachian Mountains. Despite the treaty’s provisions, however, conflict continued in the Ohio Territory, leading the Delaware people to look for safer lands farther north and west.”

CitePrintShareRecordsofrights.org. 2022. Treaty with the Delaware, 1778 | Records of Rights. [online] Available at: http://recordsofrights.org/records/227/treaty-with-the-delaware

Magazine, S. (2018, May 21). A brief balance of power-the 1778 treaty with the Delaware Nation. Smithsonian.com. Retrieved May 28, 2022, from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/blogs/national-museum-american-indian/2018/05/22/1778-delaware-treaty/

Full text of the Treaty is available here.

George Washington's Farewell Address (1797)Washington, arguably the most respected foundational leader, was very clear about not getting involved in “foreign entanglements.” It’s important to contemplate his prescriptive advice and how close (or far) America has lived up to his vision.

George Washington’s Farewell Address (1797)“...Against the insidious wiles of foreign influence (I conjure you to believe me, fellow-citizens,) the jealousy of a free people ought to be constantly awake; since history and experience prove, that foreign influence is one of the most baneful foes of Republican Government. But that jealousy, to be useful, must be impartial; else it becomes the instrument of the very influence to be avoided, instead of a defense against it. Excessive partiality for one foreign nation, and excessive dislike of another, cause those whom they actuate to see danger only on one side, and serve to veil and even second the arts of influence on the other. Real patriots, who may resist the intrigues of the favorite, are liable to become suspected and odious; while its tools and dupes usurp the applause and confidence of the people, to surrender their interests.

The great rule of conduct for us, in regard to foreign nations, is, in extending our commercial relations, to have with them as little political connection as possible. So far as we have already formed engagements, let them be fulfilled with perfect good faith. Here let us stop.”

CitePrintShareWashington, George. George Washington Papers, Series 2, Letterbooks -1799: Letterbook 24, April 3, 1793 - March 3, 1797. 1793. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/mgw2.024/?sp=229

Full text here: “Washington's Farewell Address, 1796 · George Washington's Mount Vernon.” Mount Vernon, https://www.mountvernon.org/education/primary-source-collections/primary-source-collections/article/washington-s-farewell-address-1796/. Accessed 21 January 2023.

Request on Treaty of Tripoli (1797)Article 11 of this treaty established the United States as not being considered a “Christian Nation” by a foreign country. This would play an important part in diplomatic relations, especially with “non-Christian nations.” As one of our earlier treaties, this is also important because it sets the tone for foreign policy.

CitePrintShareSenate, Request on Treaty with Tripoli. -12-30, 1805. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/mtjbib015461/.

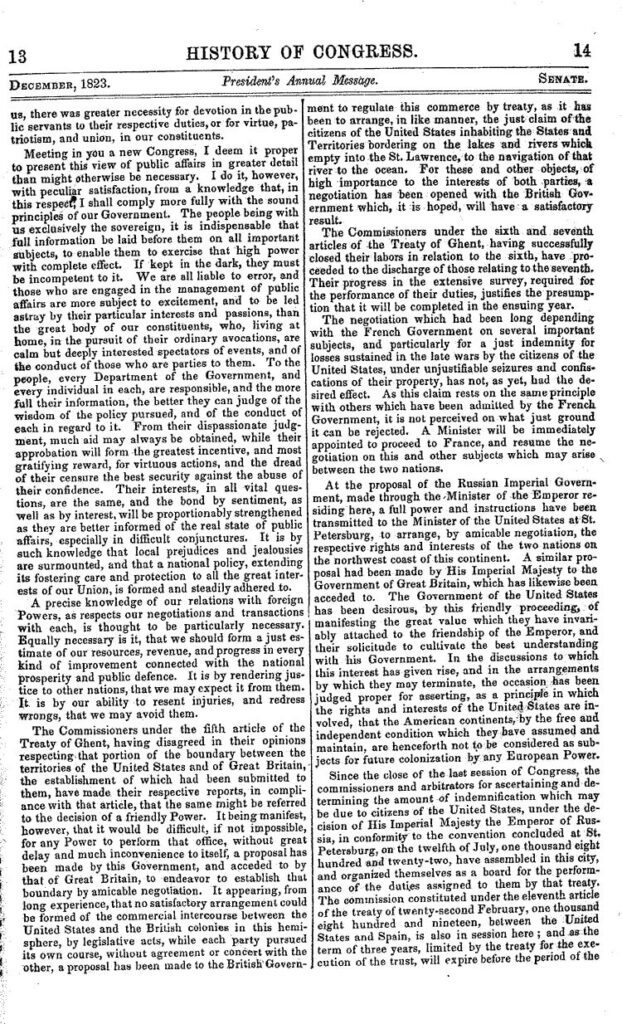

President Monroe's Annual Message (1823)Transcript“...The citizens of the United States cherish sentiments the most friendly in favor of the liberty and happiness of their fellow-men on that side of the Atlantic. In the wars of the European powers in matters relating to themselves we have never taken any part, nor does it comport with our policy to do so. It is only when our rights are invaded or seriously menaced that we resent injuries or make preparation for our defense. With the movements in this hemisphere we are of necessity more immediately connected, and by causes which must be obvious to all enlightened and impartial observers. The political system of the allied powers is essentially different in this respect from that of America. This difference proceeds from that which exists in their respective Governments; and to the defense of our own, which has been achieved by the loss of so much blood and treasure, and matured by the wisdom of their most enlightened citizens, and under which we have enjoyed unexampled felicity, this whole nation is devoted. We owe it, therefore, to candor and to the amicable relations existing between the United States and those powers to declare that we should consider any attempt on their part to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety.”

This item details “Monroe’s Doctrine” in President Monroe’s annual message to Congress. President Monroe buried a very serious global policy within the text of a routine speech. In it, he warned European powers to recognize the western hemisphere as America’s sphere of influence. His words are important to study how U.S. policy shifted in a drastic way.

CitePrintShareMemory.loc.gov. 2022. A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 - 1875. [online] Available at: <https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llac&fileName=041/llac041.db&recNum=4> [Accessed 25 April 2022].

Full text here: “Monroe Doctrine (1823) | National Archives.” National Archives |, 10 May 2022, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/monroe-doctrine. Accessed 21 January 2023.

The Patriots Get Their Beans- Political Cartoon (1845)This cartoon is a satirical look at presidential power. IN it there is “A satirical view of the scramble among newly elected President James K. Polk's 1844 campaign supporters, or "patriots," for "their beans," i.e., patronage and other official favors.”

CitePrintShareBaillie, James S., Active, and Edward Williams Clay. The Patriots Getting Their Beans. N.Y.: Lith. & pub. by James Baillie. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/2008661455/.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848)As explained by the National Archives, “This treaty, signed on February 2, 1848, ended the war between the United States and Mexico. By its terms, Mexico ceded 55 percent of its territory, including the present-day states California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming. Mexico also relinquished all claims to Texas, and recognized the Rio Grande as the southern boundary with the United States.”

ARTICLE VIII Mexicans now established in territories previously belonging to Mexico, and which remain for the future within the limits of the United States, as defined by the present treaty, shall be free to continue where they now reside, or to remove at any time to the Mexican Republic…Those who shall prefer to remain in the said territories may either retain the title and rights of Mexican citizens or acquire those of citizens of the United States. But they shall be under the obligation to make their election within one year from the date of the exchange of ratifications of this treaty.…

ARTICLE IX The Mexicans who, in the territories aforesaid, shall not preserve the character of citizens of the Mexican Republic, conformably with what is stipulated in the preceding article, shall be incorporated into the Union of the United States. and be admitted at the proper time (to be judged of by the Congress of the United States) to the enjoyment of all the rights of citizens of the United States…

ARTICLE XII In consideration of the extension acquired by the boundaries of the United States, as defined in the fifth article of the present treaty, the Government of the United States engages to pay to that of the Mexican Republic the sum of fifteen million of dollars.

1Baillie, James S., Active, and Edward Williams Clay. The Patriots Getting Their Beans. N.Y.: Lith. & pub. by James Baillie. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2008661455/>.CitePrintShare“Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) | National Archives.” National Archives |, 20 September 2022, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/treaty-of-guadalupe-hidalgo. Accessed 21 January 2023.

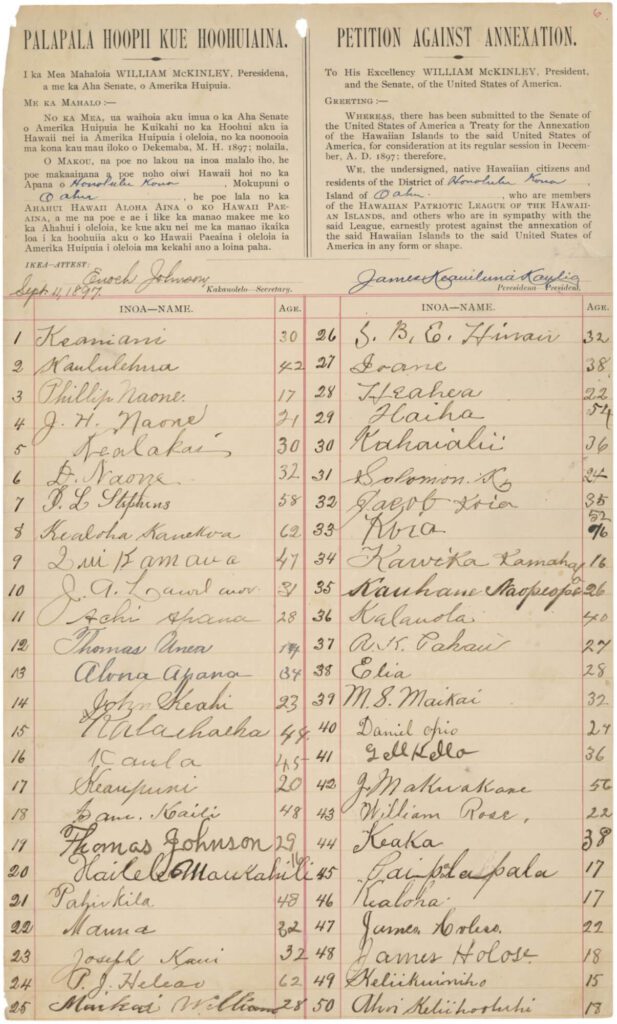

Petition Against the Annexation of Hawaii (1897)Many people who were annexed by the United States tried to resist. This document shows how native Hawaiians did not want to be part of the United States.

CitePrintSharePetition Against the Annexation of Hawaii; 1897; Petitions and Memorials, Resolutions of State Legislatures, and Related Documents, which were referred to the Committee on Foreign Relations from the 55th Congress; Petitions and Memorials, 1817 - 2000; Records of the U.S. Senate, Record Group 46; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/petition-against-annexation-hawaii, April 25, 2022]

Chicago Liberty Meeting (1899)A session held by the Anti-imperialist league, this meeting consisted of people who spoke out against the U.S. annexation of the Philippines. It represents a domestic attitude about imperial ambitions.

CitePrintShareLoc.gov. 2022. Anti-imperialist league - The World of 1898: The Spanish-American War (Hispanic Division, Library of Congress). [online] Available at: <https://www.loc.gov/rr/hispanic/1898/league.html> [Accessed 25 April 2022]

Pacifists (1917)Simply titled, “Pacifists,” this photo shows how many Americans wanted a more democratic process to foreign involvement with the implicit understanding that Americans do not desire foreign involvement.

CitePrintShareHarris & Ewing, photographer. PACIFISTS. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/2016867043/.

Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points (1918)Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen points were statements of principles that outlined why the United States was entering the first World War. In other words, it was a clear statement of what Americans were fighting for. To many historians, this marked the end of isolationism.

CitePrintShareWilson, W., 2022. Woodrow Wilson's "Fourteen Points" | Peace and a New World Order? | World Overturned | Explore | Echoes of the Great War: American Experiences of World War I | Exhibitions at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress. [online] The Library of Congress. Available at: <https://www.loc.gov/exhibitions/world-war-i-american-experiences/about-this-exhibition/world-overturned/peace-and-a-new-world-order/woodrow-wilsons-fourteen-points/> [Accessed 25 April 2022].

Follow the Pied Piper (1918)This picture shows how kids were recruited to help make “victory gardens” and help win the war effort. It’s useful for demonstrating how Americans at home supported war goals.

CitePrintShareThe World War I Garden and Victory Garden. The World War I War Garden and Victory Garden - How Does Your Garden Grow Online Exhibit State Historical Society of North Dakota. (n.d.). Retrieved June 4, 2022, from https://www.history.nd.gov/exhibits/gardening/militaryevents8.html

Mary Church Terrell Papers (1919)This source shows a time when an American argued in favor of American intervention on behalf of Haiti, Liberia, and Abyssinia (Ethiopia).

CitePrintShareTerrell, Mary Church. Mary Church Terrell Papers: Subject File, -1962; Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, 1919 to 1921 , undated. - 1921, 1919. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/mss425490340/. (Image 4)

Telegrams, Eleanor Roosevelt and President F.D. Roosevelt (1939)These images are telegrams sent from Eleanor Roosevelt, First Lady, to President Roosevelt, and his response. According to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, “in February 1939, the First Lady joined a list of prominent Americans who supported the passage of the Wagner-Rogers Bill, which proposed to ‘permit the entry of 20,000 German refugee children, ages 14 and under, into the United States’ over a two-year period and outside of the existing, restrictive immigration quota system. Though she was often outspoken on behalf of causes she cared about, this was the first time she publicly endorsed a piece of pending legislation as first lady. Eleanor Roosevelt told reporters that the bill was ‘a wise way to do a humanitarian act.’ The president never officially commented on the proposed legislation. The bill was never voted on.”

CitePrintShareEleanor Roosevelt | Americans and the Holocaust, https://exhibitions.ushmm.org/americans-and-the-holocaust/personal-story/eleanor-roosevelt.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, A Date Which Will Live in Infamy" Address (1941)Although the United States had resisted officially entering the war, the surprise bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 led to the declaration of war on Japan and its allies. This speech, which Roosevelt delivered to Congress the following day, was also broadcast live on national radio.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, A Date Which Will Live in Infamy" Address to the Congress Asking That a State of War Be Declared Between the United States and Japan. December 8, 1941:“Mr. Vice President, and Mr. Speaker, and Members of the Senate and House of Representatives:

YESTERDAY, December 7, 1941 a date which will live in infamy, the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.

The United States was at peace with that Nation and, at the solicitation of Japan, was still in conversation with its Government and its Emperor looking toward the maintenance of peace in the Pacific. Indeed, one hour after Japanese air squadrons had commenced bombing in the American Island of Oahu, the Japanese Ambassador to the United States and his colleague delivered to our Secretary of State a formal reply to a recent American message. And while this reply stated that it seemed useless to continue the existing diplomatic negotiations, it contained no threat or hint of war or of armed attack.

It will be recorded that the distance of Hawaii from Japan makes it obvious that the attack was deliberately planned many days or even weeks ago. During the intervening time the Japanese Government has deliberately sought to deceive the United States by false statements and expressions of hope for continued peace.

The attack yesterday on the Hawaiian Islands has caused severe damage to American naval and military forces. I regret to tell you that very many American lives have been lost. In addition American ships have been reported torpedoed on the high seas between San Francisco and Honolulu.

…The people of the United States have already formed their opinions and well understand the implications to the very life and safety of our Nation.

As Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy I have directed that all measures be taken for our defense. But always will our whole Nation remember the character of the onslaught against us. No matter how long it may take us to overcome this premeditated invasion, the American people in their righteous might will win through to absolute victory.

I believe that I interpret the will of the Congress and of the people when I assert that we will not only defend ourselves to the uttermost but will make it very certain that this form of treachery shall never again endanger us….

I ask that the Congress declare that since the unprovoked and dastardly attack by Japan on Sunday, December 7, 1941, a state of war has existed between the United States and the Japanese Empire.”

CitePrintShareRoosevelt, Franklin D. “Speech by Franklin D. Roosevelt, New York (Transcript).” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/afc1986022.afc1986022_ms2201/?st=text.

Presidential Proclamation 2525: Enemy Aliens (1941)This Presidential Proclamation, which followed the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, set the stage for the incarceration of Japanese Americans. Under this proclamation, even Japanese-American citizens were treated as “enemy aliens,” deprived of their Constitutional rights, and removed from their homes into internment camps for the duration of the war.

CitePrintShare“Internment Archives.” Internment Archives, https://www.internmentarchives.com/specialreports/smithsonian/smithsonian10.php.

Recruitment Posters (1942)Uncle Sam Recruitment Poster (1942)“We Can Do It!” Rosie the Riveter (1942)These two iconic images are most closely associated with their use during World War II, though the “Uncle Sam” character was first created during World War I. The Department of Defense refers to these images, intended to recruit soldiers to fight and women to work in the factories to support the war effort, as the “social media of the time.” The “We Can Do It” poster introduced the character of Rosie the Riveter, intended to attract more women to fill jobs left vacant by men leaving for the armed forces.

CitePrintShareVergun, David. “WWII Posters Aimed to Inspire, Encourage Service,” U.S. Department of Defense, 16 October 2019, https://www.defense.gov/News/Feature-Stories/story/Article/1990131/wwii-posters-aimed-to-inspire-encourage-service/.

Yalta Conference, New York Times (1945)On February 11, 1945, President Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soviet leader Josef Stalin signed the Yalta Agreement. The three world leaders negotiated plans for the governance of Europe following the end of World War II.

Potsdam Declaration (1945)The terms of the Potsdam Declaration include “that Japan …be given an opportunity to end this war,” but within two weeks, the United States deployed atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The use of these two nuclear weapons was the only such use in history. The final statement of the Proclamation, included in this excerpt, hints at that threat. While Japan did surrender after the use of the atomic bombs, some historians question whether the deployment of the weapons was necessary for surrender or whether the surrender could have been secured without it.

Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender Issued, at Potsdam, July 26, 1945- We―the President of the United States, the President of the National Government of the Republic of China, and the Prime Minister of Great Britain, representing the hundreds of millions of our countrymen, have conferred and agree that Japan shall be given an opportunity to end this war.

- The prodigious land, sea and air forces of the United States, the British Empire and of China, many times reinforced by their armies and air fleets from the west, are poised to strike the final blows upon Japan. This military power is sustained and inspired by the determination of all the Allied Nations to prosecute the war against Japan until she ceases to resist.

- The occupying forces of the Allies shall be withdrawn from Japan as soon as these objectives have been accomplished and there has been established in accordance with the freely expressed will of the Japanese people a peacefully inclined and responsible government.

- We call upon the government of Japan to proclaim now the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces, and to provide proper and adequate assurances of their good faith in such action. The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.

CitePrintShare“Potsdam Declaration - Nuclear Museum.” Atomic Heritage Foundation, https://ahf.nuclearmuseum.org/ahf/key-documents/potsdam-declaration/.

The Causes of World War (1951)In this draft of a speech WEB DuBois was critiquing war as a means to perpetuate supremacy. He argued against involvement.

CitePrintShareDuBois, W., 2022. The causes of world war, September 28, 1951. [online] Credo.library.umass.edu. Available at: https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b201-i071 [Accessed 25 April 2022].

U.S.S.R. Moscow, Mr. K[hrushchev] & V.P. Nixon on T.V. at American exhibit (1959)U.S.S.R. Moscow, Mr. K[hrushchev] & V.P. Nixon on T.V. at American exhibit (1959)This source shows the impact television made on foreign policy. Nixon and Kruschev debated about the merits of their respective economic types.

CitePrintShareLoc.gov. 2022. U.S.S.R. Moscow, Mr. K[hrushchev] & V.P. Nixon on T.V. at American exhibit. [online] Available at: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ppmsca.19730/ [Accessed 25 April 2022].

Tick-Tock-Tock Political Cartoon (1962)This satirical cartoon shows the seemingly inevitable nature of nuclear war, after getting entangled with The Soviet Union. It can be used to show how close the United States came to nuclear war and the results of brinkmanship policy.

CitePrintShareBlock, H., 2022. "Tick-tock-tick". [online] Loc.gov. Available at: <https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2011661783/> [Accessed 25 April 2022].

Anti-Vietnam War Protest (1968)A massive movement against the war in Vietnam, protestors took to the streets to voice their outrage in U.S. policy, arguing for less intervention in global affairs.

CitePrintShareLoc.gov. 2022. [Anti-Vietnam war protest and demonstration in front of the White House in support of singer Eartha Kitt]. [online] Available at: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2010646065/ [Accessed 25 April 2022].

Camp David Summit (1978)This meeting between the U.S. president and leaders from Egypt and Israel successfully produced the basis for an Egyptian-Israeli peace, in the form of two “Framework” documents, which laid out the principles of a bilateral peace agreement as well as a formula for Palestinian self-government in Gaza and the West Bank.

1U.S. Department of State. (n.d.). U.S. Department of State. Retrieved June 2, 2022, from https://history.state.gov/milestones/1977-1980/camp-david#:~:text=In%20the%20end%2C%20while%20the,Gaza%20and%20the%20West%20Bank.

CitePrintShareU.S. Department of State. (n.d.). U.S. Department of State. Retrieved June 2, 2022, from https://history.state.gov/milestones/1977-1980/camp-david#:~:text=In%20the%20end%2C%20while%20the,Gaza%20and%20the%20West%20Bank.

Education for American Democracy

Download the Roadmap and Report

Download the Educating for American Democracy Roadmap and Report Documents

Get the Roadmap and Report to unlock the work of over 300 leading scholars, educators, practitioners, and others who spent thousands of hours preparing this robust framework and guiding principles. The time is now to prioritize history and civics.

Your contact information will not be shared, and only used to send additional updates and materials from Educating for American Democracy, from which you can unsubscribe.

We the People

This theme explores the idea of “the people” as a political concept–not just a group of people who share a landscape but a group of people who share political ideals and institutions.

Institutional & Social Transformation

This theme explores how social arrangements and conflicts have combined with political institutions to shape American life from the earliest colonial period to the present, investigates which moments of change have most defined the country, and builds understanding of how American political institutions and society changes.

Contemporary Debates & Possibilities

This theme explores the contemporary terrain of civic participation and civic agency, investigating how historical narratives shape current political arguments, how values and information shape policy arguments, and how the American people continues to renew or remake itself in pursuit of fulfillment of the promise of constitutional democracy.

Civic Participation

This theme explores the relationship between self-government and civic participation, drawing on the discipline of history to explore how citizens’ active engagement has mattered for American society and on the discipline of civics to explore the principles, values, habits, and skills that support productive engagement in a healthy, resilient constitutional democracy. This theme focuses attention on the overarching goal of engaging young people as civic participants and preparing them to assume that role successfully.

Our Changing landscapes

This theme begins from the recognition that American civic experience is tied to a particular place, and explores the history of how the United States has come to develop the physical and geographical shape it has, the complex experiences of harm and benefit which that history has delivered to different portions of the American population, and the civics questions of how political communities form in the first place, become connected to specific places, and develop membership rules. The theme also takes up the question of our contemporary responsibility to the natural world.

A New Government & Constitution

This theme explores the institutional history of the United States as well as the theoretical underpinnings of constitutional design.

A People in the World

This theme explores the place of the U.S. and the American people in a global context, investigating key historical events in international affairs,and building understanding of the principles, values, and laws at stake in debates about America’s role in the world.

The Seven Themes

The Seven Themes provide the organizational framework for the Roadmap. They map out the knowledge, skills, and dispositions that students should be able to explore in order to be engaged in informed, authentic, and healthy civic participation. Importantly, they are neither standards nor curriculum, but rather a starting point for the design of standards, curricula, resources, and lessons.

Driving questions provide a glimpse into the types of inquiries that teachers can write and develop in support of in-depth civic learning. Think of them as a starting point in your curricular design.

Learn more about inquiry-based learning in the Pedagogy Companion.

Sample guiding questions are designed to foster classroom discussion, and can be starting points for one or multiple lessons. It is important to note that the sample guiding questions provided in the Roadmap are NOT an exhaustive list of questions. There are many other great topics and questions that can be explored.

Learn more about inquiry-based learning in the Pedagogy Companion.

The Seven Themes

The Seven Themes provide the organizational framework for the Roadmap. They map out the knowledge, skills, and dispositions that students should be able to explore in order to be engaged in informed, authentic, and healthy civic participation. Importantly, they are neither standards nor curriculum, but rather a starting point for the design of standards, curricula, resources, and lessons.

The Five Design Challenges

America’s constitutional politics are rife with tensions and complexities. Our Design Challenges, which are arranged alongside our Themes, identify and clarify the most significant tensions that writers of standards, curricula, texts, lessons, and assessments will grapple with. In proactively recognizing and acknowledging these challenges, educators will help students better understand the complicated issues that arise in American history and civics.

Motivating Agency, Sustaining the Republic

- How can we help students understand the full context for their roles as civic participants without creating paralysis or a sense of the insignificance of their own agency in relation to the magnitude of our society, the globe, and shared challenges?

- How can we help students become engaged citizens who also sustain civil disagreement, civic friendship, and thus American constitutional democracy?

- How can we help students pursue civic action that is authentic, responsible, and informed?

America’s Plural Yet Shared Story

- How can we integrate the perspectives of Americans from all different backgrounds when narrating a history of the U.S. and explicating the content of the philosophical foundations of American constitutional democracy?

- How can we do so consistently across all historical periods and conceptual content?

- How can this more plural and more complete story of our history and foundations also be a common story, the shared inheritance of all Americans?

Simultaneously Celebrating & Critiquing Compromise

- How do we simultaneously teach the value and the danger of compromise for a free, diverse, and self-governing people?

- How do we help students make sense of the paradox that Americans continuously disagree about the ideal shape of self-government but also agree to preserve shared institutions?

Civic Honesty, Reflective Patriotism

- How can we offer an account of U.S. constitutional democracy that is simultaneously honest about the wrongs of the past without falling into cynicism, and appreciative of the founding of the United States without tipping into adulation?

Balancing the Concrete & the Abstract

- How can we support instructors in helping students move between concrete, narrative, and chronological learning and thematic and abstract or conceptual learning?

Each theme is supported by key concepts that map out the knowledge, skills, and dispositions students should be able to explore in order to be engaged in informed, authentic, and healthy civic participation. They are vertically spiraled and developed to apply to K—5 and 6—12. Importantly, they are not standards, but rather offer a vision for the integration of history and civics throughout grades K—12.

Helping Students Participate

- How can I learn to understand my role as a citizen even if I’m not old enough to take part in government? How can I get excited to solve challenges that seem too big to fix?

- How can I learn how to work together with people whose opinions are different from my own?

- How can I be inspired to want to take civic actions on my own?

America’s Shared Story

- How can I learn about the role of my culture and other cultures in American history?

- How can I see that America’s story is shared by all?

Thinking About Compromise

- How can teachers teach the good and bad sides of compromise?

- How can I make sense of Americans who believe in one government but disagree about what it should do?

Honest Patriotism

- How can I learn an honest story about America that admits failure and celebrates praise?

Balancing Time & Theme

- How can teachers help me connect historical events over time and themes?

The Six Pedagogical Principles

EAD teacher draws on six pedagogical principles that are connected sequentially.

Six Core Pedagogical Principles are part of our Pedagogy Companion. The Pedagogical Principles are designed to focus educators’ effort on techniques that best support the learning and development of student agency required of history and civic education.

EAD teachers commit to learn about and teach full and multifaceted historical and civic narratives. They appreciate student diversity and assume all students’ capacity for learning complex and rigorous content. EAD teachers focus on inclusion and equity in both content and approach as they spiral instruction across grade bands, increasing complexity and depth about relevant history and contemporary issues.

Growth Mindset and Capacity Building

EAD teachers have a growth mindset for themselves and their students, meaning that they engage in continuous self-reflection and cultivate self-knowledge. They learn and adopt content as well as practices that help all learners of diverse backgrounds reach excellence. EAD teachers need continuous and rigorous professional development (PD) and access to professional learning communities (PLCs) that offer peer support and mentoring opportunities, especially about content, pedagogical approaches, and instruction-embedded assessments.

Building an EAD-Ready Classroom and School

EAD teachers cultivate and sustain a learning environment by partnering with administrators, students, and families to conduct deep inquiry about the multifaceted stories of American constitutional democracy. They set expectations that all students know they belong and contribute to the classroom community. Students establish ownership and responsibility for their learning through mutual respect and an inclusive culture that enables students to engage courageously in rigorous discussion.

Inquiry as the Primary Mode for Learning

EAD teachers not only use the EAD Roadmap inquiry prompts as entry points to teaching full and complex content, but also cultivate students’ capacity to develop their own deep and critical inquiries about American history, civic life, and their identities and communities. They embrace these rigorous inquiries as a way to advance students’ historical and civic knowledge, and to connect that knowledge to themselves and their communities. They also help students cultivate empathy across differences and inquisitiveness to ask difficult questions, which are core to historical understanding and constructive civic participation.

Practice of Constitutional Democracy and Student Agency

EAD teachers use their content knowledge and classroom leadership to model our constitutional principle of “We the People” through democratic practices and promoting civic responsibilities, civil rights, and civic friendship in their classrooms. EAD teachers deepen students’ grasp of content and concepts by creating student opportunities to engage with real-world events and problem-solving about issues in their communities by taking informed action to create a more perfect union.

Assess, Reflect, and Improve

EAD teachers use assessments as a tool to ensure all students understand civics content and concepts and apply civics skills and agency. Students have the opportunity to reflect on their learning and give feedback to their teachers in higher-order thinking exercises that enhance as well as measure learning. EAD teachers analyze and utilize feedback and assessment for self-reflection and improving instruction.

EAD teachers commit to learn about and teach full and multifaceted historical and civic narratives. They appreciate student diversity and assume all students’ capacity for learning complex and rigorous content. EAD teachers focus on inclusion and equity in both content and approach as they spiral instruction across grade bands, increasing complexity and depth about relevant history and contemporary issues.

Growth Mindset and Capacity Building

EAD teachers have a growth mindset for themselves and their students, meaning that they engage in continuous self-reflection and cultivate self-knowledge. They learn and adopt content as well as practices that help all learners of diverse backgrounds reach excellence. EAD teachers need continuous and rigorous professional development (PD) and access to professional learning communities (PLCs) that offer peer support and mentoring opportunities, especially about content, pedagogical approaches, and instruction-embedded assessments.

Building an EAD-Ready Classroom and School

EAD teachers cultivate and sustain a learning environment by partnering with administrators, students, and families to conduct deep inquiry about the multifaceted stories of American constitutional democracy. They set expectations that all students know they belong and contribute to the classroom community. Students establish ownership and responsibility for their learning through mutual respect and an inclusive culture that enables students to engage courageously in rigorous discussion.

Inquiry as the Primary Mode for Learning

EAD teachers not only use the EAD Roadmap inquiry prompts as entry points to teaching full and complex content, but also cultivate students’ capacity to develop their own deep and critical inquiries about American history, civic life, and their identities and communities. They embrace these rigorous inquiries as a way to advance students’ historical and civic knowledge, and to connect that knowledge to themselves and their communities. They also help students cultivate empathy across differences and inquisitiveness to ask difficult questions, which are core to historical understanding and constructive civic participation.

Practice of Constitutional Democracy and Student Agency

EAD teachers use their content knowledge and classroom leadership to model our constitutional principle of “We the People” through democratic practices and promoting civic responsibilities, civil rights, and civic friendship in their classrooms. EAD teachers deepen students’ grasp of content and concepts by creating student opportunities to engage with real-world events and problem-solving about issues in their communities by taking informed action to create a more perfect union.

Assess, Reflect, and Improve

EAD teachers use assessments as a tool to ensure all students understand civics content and concepts and apply civics skills and agency. Students have the opportunity to reflect on their learning and give feedback to their teachers in higher-order thinking exercises that enhance as well as measure learning. EAD teachers analyze and utilize feedback and assessment for self-reflection and improving instruction.

![U.S.S.R. Moscow, Mr. K[hrushchev] & V.P. Nixon on T.V. at American exhibit (1959)](/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/U.S.S.R.-Moscow-Mr.-Khrushchev-V.P.-Nixon-on-T.V.-at-American-exhibit-1959.jpg)