The curated resources linked below are an initial sample of the resources coming from a collaborative and rigorous review process with the EAD Content Curation Task Force.

Reset All

Reset All

The promises of equal rights in the Declaration of Independence and of political peoplehood in the Constitution were not granted to Black women throughout much of American history. Black women were brought to the colonies violently in the slave trade, or born into slavery in North America. Most were deprived of all freedoms as enslaved people. Black women were first entirely denied access to education, and then to equal access. They were disenfranchised, even when Black men and white women were ultimately granted the right to vote. Nonetheless, the voices of Black women resonate throughout American history in letters, speeches, personal narratives, court cases, journalism, higher institutions of learning, and political leadership. In all eras of American history, Black women use their voices to fight for the rights they were denied and to dismantle the legal, political, and philosophical barriers that stood in their way.

This Spotlight Kit features the voices of Black women who paved the way for the election of Kamala Harris as the nation’s first Black and Asian American Vice President and Ketanji Brown Jackson as the first Black woman on the Supreme Court.

The resources in this spotlight kit are intended for classroom use, and are shared here under a CC-BY-SA license. Teachers, please review the copyright and fair use guidelines.

The Roadmap

- Primary Resources by Era/Date1773 (1)1781 (1)1833 (1)1851 (1)1848 (1)1891 (1)1892 (1)1898 (1)1915 (1)1920 (1)1955 (2)1962 (1)1964 (1)1968 (2)1970 (1)1971 (1)2001 (1)

- All 19 Primary ResourcesPhillis Wheatley by an unidentified artist, Engraving on paper (1773)National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

The National Portrait Gallery describes the singular achievement of Phillis Wheatley: “In 1773, Phillis Wheatley accomplished something that no other woman of her status had done. When her book of poetry, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, appeared, she became the first American slave, the first person of African descent, and only the third colonial American woman to have her work published.”

CitePrintShare“Phillis Wheatley: Her Life, Poetry, and Legacy | National Portrait Gallery.” National Portrait Gallery, https://npg.si.edu/blog/phillis-wheatley-her-life-poetry-and-legacy.

Brom & Bett vs. J. Ashley Esq. (1781)“Mumbet,” who later took the name Elizabeth Freeman, was an enslaved woman given by one man, Pieter Hogeboom, to another, Colonel John Ashley, when Ashley married Hogeboom’s daughter in Massachusetts.

Mumbet sued for her freedom in 1781. “According to historian Arthur Zilversmit the people of Berkshire County then adopted Mumbet’s cause to test the constitutionality of slavery following the passage of the new state constitution. ‘Brom and Bett’ were the first enslaved African Americans to be set free under the new Massachusetts State Constitution of 1780.”

Court Records, Berkshire County Courthouse Great Barrington, Massachusetts Inferior Court of Common Pleas May 28, 1781 Volume 4A, page 55, NumberBrom & Bett vs. J. Ashley Esq.

“…After a full hearing of this case the evidence therein being produced, the same case is committed to the Jury Jonathan Holcom Foreman and his fellows who being duly sworn return this verdict that in this case the Jury find that the aforesaid Brom & Bett are not and were not at the time of the purchase of the original writ the legal Negro servants of him the said John Ashley during their life and [assess] thirty shillings damages wherefore it is considered by the Court Adjudged and determined that the said Brom & Bett are not, nor were they at the time of the purchase of the original writ the legal Negro of the said John Ashley during life, and that the said Brom & Bett do recover against the said John Ashley the sum of thirty shillings lawful silver Money, Damages…”

CitePrintShare“Mumbet Court Records – Elizabeth Freeman.” Elizabeth Freeman, https://elizabethfreeman.mumbet.com/who-is-mumbet/mumbet-court-records/.

Maria W. Stewart, “An Address at the African Masonic Hall” (1833)Maria W. Stewart, “An Address at the African Masonic Hall” (1833)Transcript...Our condition as a people has been low for hundreds of years, and it will continue to be so, unless, by the true piety and virtue we strive, to regain that which we have lost. White Americans, by their prudence, economy and exertions, have sprung up and become one of the most flourishing nations in the world, distinguished for their knowledge of the arts and sciences, for their polite literature. Whilst our minds are vacant and starving for want of knowledge, theirs are filled to overflowing. Most of our color have been taught to stand in fear of the white man from their earliest infancy, to work as soon as they could walk, and call ‘master’ before they scarce could lisp the name of mother. Continual fear and laborious servitude have in some degree lessened in us that natural force and energy which belong to man; or else, in defiance of opposition, our men, before this would have nobly and boldly contended for their rights. But give the man of color an equal opportunity with the white, from the cradle to manhood, and from manhood to the grave, and you would discover the dignified statesman, the man of science, and the philosopher. But there is no such opportunity for the sons of Africa, and I fear that our powerful ones are fully determined that there never shall be. Forbid, ye Powers on High, that it should any longer be said that our men possess no force. 0 ye sons of Africa, when will your voices be heard in our legislative halls, in defiance of your enemies, contending for equal rights and liberty?

According to the National Park Service’s biography of Maria Stewart, “Abolitionist and women's rights advocate Maria W. Stewart was one of the first women of any race to speak in public in the United States. She was also the first Black American woman to write and publish a political manifesto. Her calls for Black people to resist slavery, oppression, and exploitation were radical. Stewart's thinking and speaking style influenced Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper.”

CitePrintShare“(1833) Maria W. Stewart, "An Address at the African Masonic Hall" •.” Blackpast, 24 October 2011, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/1833-maria-w-stewart-address-african-masonic-hall/.

“Maria W. Stewart (U.S.” National Park Service, 16 January 2023, https://www.nps.gov/people/maria-w-stewart.htm.

The Anti-Slavery Bugle, Sojourner Truth at the Women’s Rights Convention (1851)Born into slavery in New York in 1797, Sojourner Truth (originally Isabella Bomfree) escaped to an abolitionist family that helped her secure her freedom. An activist for abolitionism, civil and women’s rights, Truth fought against sexism in the abolitionist movement and racism in the women’s movement. The original “Ain’t I A Woman” speech by Sojourner Truth was transcribed by Marius Robinson, a journalist who was in the audience at the Woman's Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio, on May 29, 1851.

“One of the most unique and interesting speeches at the convention was made by Sojourner Truth, an emancipated slave….she came forward to the platform and addressing the President said with great simplicity:‘...I want to say a few words about this matter. I am a woman’s rights. I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that? I am as strong as any man that is now. As for intellect, all I can say is, if woman have a pint and man a quart–why can’t she have her little pint full? You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear we will take too much, –for we can’t take more than our pint’ll hold. The poor men seem to be all in confusion, and don’t know what to do. Why children, if you have woman’s rights and you give it to her and you will feel better….’”

CitePrintShareAnti-slavery bugle. (New-Lisbon, Ohio), 21 June 1851. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83035487/1851-06-21/ed-1/seq-4/

Susie King Taylor: Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33d United States Colored Troops Late 1st S. C. VolunteersSusie King Taylor escaped slavery, became a teacher at age 14, and served as a Civil War nurse for more than four years, working alongside Clara Barton. Taylor was the only Black woman to publish a memoir of her Civil War experiences.

[In Camp Saxton, 1863]“I taught a great many of the comrades in Company E to read and write, when they were off duty. Nearly all were anxious to learn. My husband taught some also when it was convenient for him. I was very happy to know my efforts were successful in camp, and also felt grateful for the appreciation of my services. I gave my services willingly for four years and three months without receiving a dollar. I was glad, however, to be allowed to go with the regiment, to care for the sick and afflicted comrades.” (21)

“While the fighting was on, a friend, Lizzie Lancaster, and I stopped at several of the rebel homes, and after talking with some of the women and children we asked them if they had any food. They claimed to have only some hard-tack, and evidently did not care to give us anything to eat, but this was not surprising. They were bitterly against our people and had no mercy or sympathy for us.

The second day, our boys were reinforced by a regiment of white soldiers, a Maine regiment, and by cavalry, and had quite a fight. On the third day, Edward Herron, who was a fine gunner on the steamer John Adams, came on shore, bringing a small cannon, which the men pulled along for more than five miles. This cannon was the only piece for shelling. On coming upon the enemy, all secured their places, and they had a lively fight, which lasted several hours, and our boys were nearly captured by the Confederates; but the Union boys carried out all their plans that day, and succeeded in driving the enemy back. After this skirmish, every afternoon between four and five o'clock the Confederate General Finegan would send a flag of truce to Colonel Higginson, warning him to send all women and children out of the city, and threatening to bombard it if this was not done.” (23-24)

“I learned to handle a musket very well while in the regiment, and could shoot straight and often hit the target. I assisted in cleaning the guns and used to fire them off, to see if the cartridges were dry, before cleaning and reloading, each day. I thought this great fun. I was also able to take a gun all apart, and put it together again.” (27)

CitePrintShareReminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33d United States Colored Troops Late 1st S. C. Volunteers: Electronic Edition. Taylor, Susie King, b. 1848 https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/taylorsu/tayhttps://www.gutenberg.org/files/14975/14975-h/14975-h.htmlorsu.html

Frances E.W. Harper, Sketches of Southern Life (1891)Born free in Maryland in 1825, Frances E.W. Harper spent her life as a poet, an abolitionist, and a champion of women’s rights. She also helped enslaved people escape through the Underground Railroad, and she published several novels in addition to her poetry. Like many of the women featured in this Spotlight Kit, her writing explored the intersectionality of race, class, and gender.

AUNT CHLOE (excerpt)

I remember, well remember, That dark and dreadful day, When they whispered to me, “Chloe, Your children’s sold away!”It seemed as if a bullet Had shot me through and through, And I felt as if my heart-strings Was breaking right in two.

And I says to cousin Milly, “There must be some mistake; Where’s Mistus?” “In the great house crying— Crying like her heart would break.

“And the lawyer’s there with Mistus; Says he’s come to ’ministrate, ’Cause when master died he just left Heap of debt on the estate.

“And I thought ’twould do you good To bid your boys good-bye— To kiss them both and shake their hands, And have a hearty cry.

“Oh! Chloe, I knows how you feel, ’Cause I’se been through it all; I thought my poor old heart would break, When master sold my Saul.”

CitePrintShareHarper, Frances Ellen Watkins. “Sketches of Southern Life.” The Project Gutenberg eBook of Sketches of Southern Life, by Frances E. Watkins Harper, www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/69249/pg69249-images.html.

Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1892)Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1892)TranscriptFrom this exposition of the race issue in lynch law, the whole matter is explained by the well-known opposition growing out of slavery to the progress of the race. This is crystalized in the oft-repeated slogan: ‘This is a white man's country and the white man must rule.’ The South resented giving the Afro-American his freedom, the ballot box and the Civil Rights Law. The raids of the Ku-Klux and White Liners to subvert reconstruction government, the Hamburg and Ellerton, S.C., the Copiah County, Miss., and the Layfayette Parish, La., massacres were excused as the natural resentment of intelligence against government by ignorance….

One by one the Southern States have legally(?) disfranchised the Afro-American, and since the repeal of the Civil Rights Bill nearly every Southern State has passed separate car laws with a penalty against their infringement. The race regardless of advancement is penned into filthy, stifling partitions cut off from smoking cars. All this while, although the political cause has been removed, the butcheries of black men at Barnwell, S.C., Carrolton, Miss., Waycross, Ga., and Memphis, Tenn., have gone on; also the flaying alive of a man in Kentucky, the burning of one in Arkansas, the hanging of a fifteen-year-old girl in Louisiana, a woman in Jackson, Tenn., and one in Hollendale, Miss., until the dark and bloody record of the South shows 728 Afro-Americans lynched during the past eight years. Not fifty of these were for political causes; the rest were for all manner of accusations from that of rape of white women, to the case of the boy Will Lewis who was hanged at Tullahoma, Tenn., last year for being drunk and ‘sassy’ to white folks.

These statistics compiled by the Chicago Tribune were given the first of this year (1892). Since then, not less than one hundred and fifty have been known to have met violent death at the hands of cruel bloodthirsty mobs during the past nine months.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett was an outspoken activist for many causes. In 1884, she sued a train company for wrongfully removing her from a first-class train for which she had purchased a ticket. Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, she used her work as a journalist to investigate and expose the lynching of Black men and women, including the publication of this document. She also fought for women’s suffrage, even marching with the movement over the objections of some white participants who did not want Black women to participate.

CitePrintShare“Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases.” The Project Gutenberg eBook of Southern Horrors: Lynch Law In All Its Phases, by Ida B. Wells-Barnett., www.gutenberg.org/files/14975/14975-h/14975-h.htm.

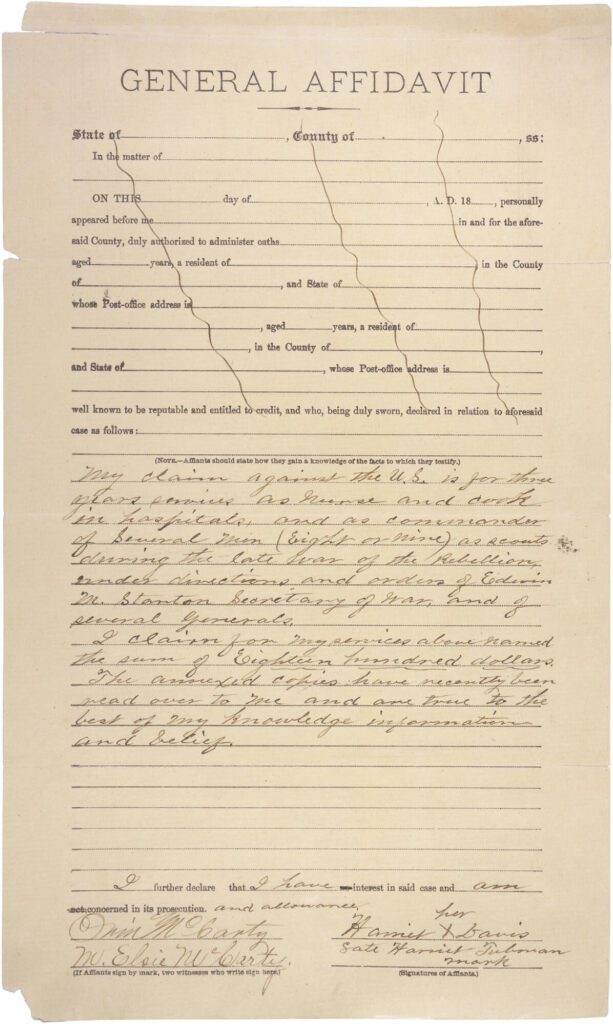

General Affidavit of Harriet Tubman Davis regarding payment for services rendered during the Civil War (1898)According to the National Women’s History Museum and historian Debra Michals, “Harriet Tubman was enslaved, escaped, and helped others gain their freedom as a ‘conductor’ of the Underground Railroad. Tubman also served as a scout, spy, guerrilla soldier, and nurse for the Union Army during the Civil War. She is considered the first African American woman to serve in the military.” In this document, Tubman petitioned for back pay for her services to the military, ultimately securing a pension of $8 a month as the widow of a Union soldier and $20 for her service. When she died, she was buried with military honors.

CitePrintSharePage 1 of General Affidavit of Harriet Tubman Davis regarding payment for services rendered during the Civil War, c. 1898, RG 233, Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, National Archives https://www.archives.gov/legislative/features/claim-of-harriet-tubman

Michals, Debra. “Harriet Tubman Biography.” National Women's History Museum, https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/harriet-tubman.

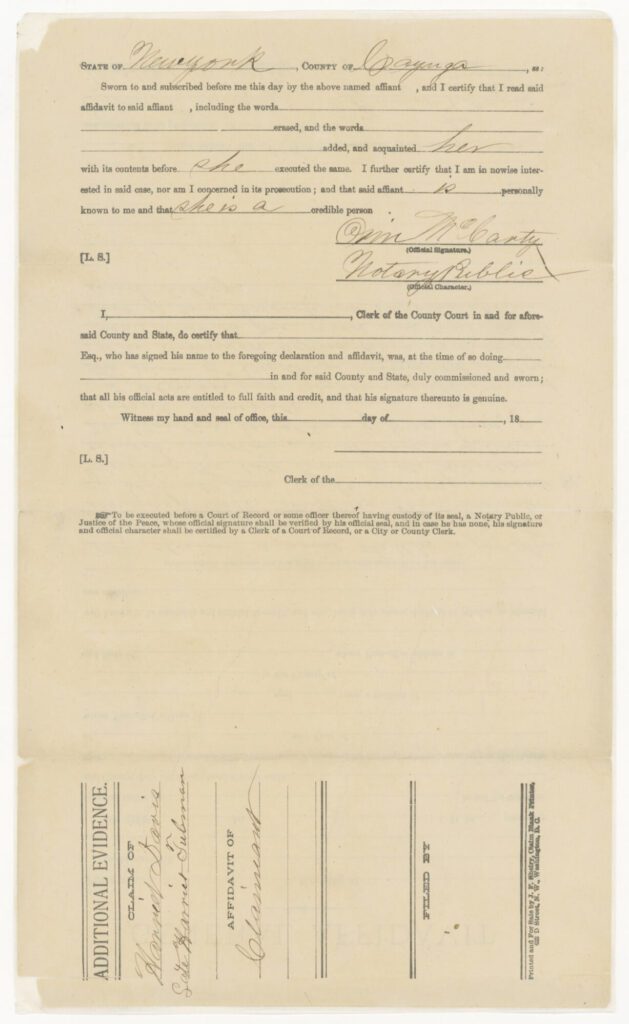

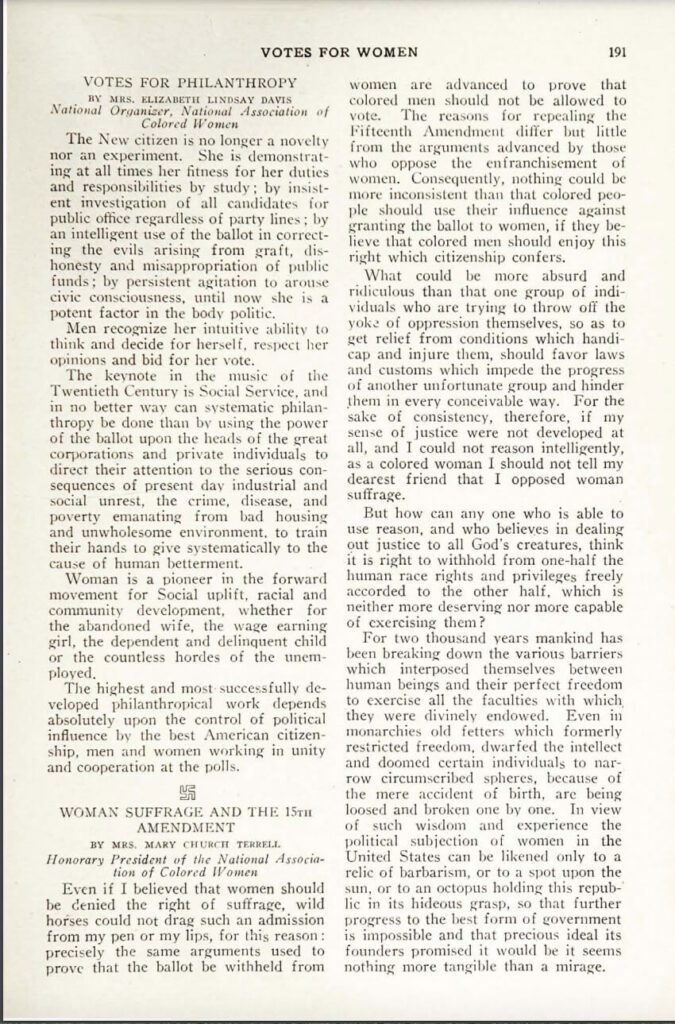

Woman Suffrage and the 15th Amendment, Mary Church Terrell in The Crisis (1915)The Crisis was the official magazine of the NAACP, and this issue from 1915 was dedicated to the issue of women’s suffrage. Mary Church Terrell’s activism began with her involvement in Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s anti-lynching movement, following the death by lynching of a friend in Memphis. As the founder of the National Association for Colored Women (NACW), she fought for Black women’s suffrage specifically (and for women’s suffrage broadly) as the key to ultimate equality.

CitePrintShare“The Crisis, Vol. 10, No. 4.” Brown University Library, library.brown.edu/pdfs/128895937640750.pdf.

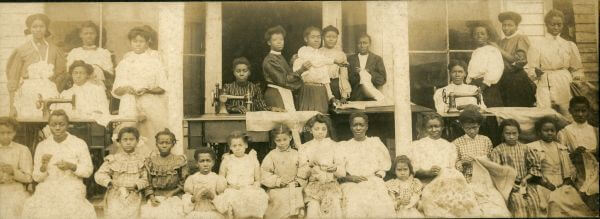

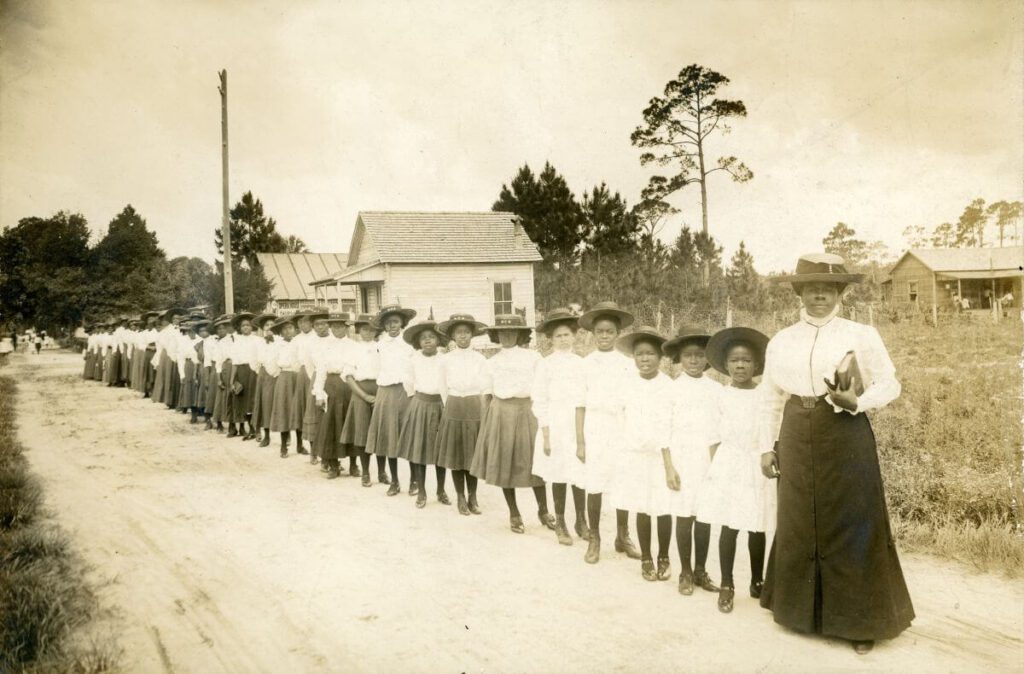

“A Philosophy of Education for Negro Girls” Mary McLeod Bethune (1920)Literary and Industrial Training School for Negro Girls, Daytona FL (1920)Transcript...If there is to be any distinctive difference between the education of the Negro girl and the Negro boy, it should be that of consideration for the unique responsibility of this girl in the world today. The challenge to the Negro home is one which dares the Negro to develop initiative to solve his own problem, to work out his own problems, to work out his difficulties in a superior fashion, and to finally come into his right as an American Citizen, because he is tolerated. This is the moral responsibility of the education of the Negro girl; It must become a part of her thinking; her activities must lead her into such endeavors early in her educational life; this training must be inculcated into the school curricula so that the result may be a natural expression — born into her children. Such is the natural endowment which her education must make it possible for her to bequeath to the future of the Negro race.

The education of the Negro girl must embrace a larger appreciation for good citizenship in the home. Our girls must be taught cleanliness, beauty and thoughtfulness and their application in making home life possible. For proper home life provides the proper atmosphere for life everywhere else. The ideas of home must not forever be talked about; they must be living factors built into the everyday educational experiences of our girls.

Negro girls must receive also a peculiar appreciation for the expression of the creative self. They must be taught to realize their responsibility to find ways whereby the home and the schoolroom may encourage our youth to be creative; to develop to the fullest extent the inner urges that make them distinctive and that will lead them to be worthy contributors to the life of the little worlds in which they will live. This in itself will do more to remove the walls of inter-racial prejudice and build up intra-racial confidence and pride than many of our educational tools and devices.

Mary McLeod-Bethune was one of seventeen children, raised in part working in the fields of the plantation where her parents had been formerly enslaved. She became a prominent educator. The school for girls, pictured and described here, ultimately merged with the all-male Cookman Institute and in 1929 became Bethune-Cookman College.

CitePrintShare“Florida Memory • Primary Source Set: Mary McLeod Bethune.” Florida Memory, State Library and Archives of Florida. www.floridamemory.com/items/show/341521.

McLeod Bethune, Mary. "A Philosophy of Education for Negro Girls." Speaking While Female Speech Bank, 1920, https://speakingwhilefemale.co/education-bethune/.

Fingerprint Card of Rosa Parks Civil Case 1147 Browder, et al. v. Gayle, et al (1955)Fingerprint Card of Rosa Parks Civil Case 1147 Browder, et al. v. Gayle, et al (1955)Transcript“People always say that I didn’t give up my seat because I was tired, but that isn’t true. I was not tired physically, or no more tired than I usually was at the end of a working day. I was not old, although some people have an image of me as being old then. I was forty-two. No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”

(from her 1992 autobiography)

Although Rosa Parks is well known as the woman whose actions initiated the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955, her story is misunderstood and mischaracterized. As historian Stephanie Townrow explains, “Rosa Parks had been an activist for civil rights most of her life, and was an active member of the Montgomery NAACP chapter. In her 1992 autobiography, Parks challenged the simplistic narrative that she was just too tired after a long day’s work to give up her seat.” A passage from Parks’ autobiography is cited here, along with the fingerprinting card from the arrest that followed her refusal to move.

CitePrintShareFingerprint Card of Rosa Parks Civil Case 1147 Browder, et al. v. Gayle, et al.; U.S. District Court for Middle District of Alabama, Northern (Montgomery) Division Record Group 21: Records of the District Court of the United States National Archives and Records Administration-Southeast Region, East Point, GA. https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/rosa-parks

Quote: Townrow, Stephanie. “Rosa Parks Refuses to Move: On This Day, December 1 | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.” Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History |, 1 December 2015, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/news/rosa-parks-refuses-move-day-december-1.

Zora Neale Hurston’s Letter to The Orlando Sentinel (1955)Zora Neale Hurston’s Letter to The Orlando Sentinel (August 11, 1955)TranscriptEditor: I promised God and some other responsible characters, including a bench of bishops, that I was not going to part my lips concerning the U.S. Supreme Court decision on ending segregation in the public schools of the South. But since a lot of time has passed and no one seems to touch on what to me appears to be the most important point in the hassle, I break my silence just this once. Consider me as just thinking out loud.

The whole matter revolves around the self-respect of my people. How much satisfaction can I get from a court order for somebody to associate with me who does not wish me near them? The American Indian has never been spoken of as a minority and chiefly because there is no whine in the Indian. Certainly he fought, and valiantly for his lands, and rightfully so, but it is inconceivable of an Indian to seek forcible association with anyone. His well known pride and self-respect would save him from that. I take the Indian position….

…If there are not adequate Negro schools in Florida, and there is some residual, some inherent and unchangeable quality in white schools, impossible to duplicate anywhere else, then I am the first to insist that Negro children of Florida be allowed to share this boon. But if there are adequate Negro schools and prepared instructors and instructions, then there is nothing different except the presence of white people.

For this reason, I regard the ruling of the U.S. Supreme Court as insulting rather than honoring my race….

Zora Neale Hurston is most famous as an anthropologist and novelist. She wove Black folklore, linguistics, and culture into her writing, including the collection Mules and Men and the novel Their Eyes Were Watching God. In this letter, she expresses controversial opposition to the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas.

CitePrintShare“(1955) Zora Neale Hurston's Letter to the Orlando Sentinel •.” Blackpast, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/zora-neale-hurston-s-letter-orlando-sentinel-1955/.

Constance Baker Motley, interview with The Visionary Project, “My Inspiration to Be a Lawyer”TranscriptConstance Baker Motley with James Meredith and lawyer Jack Greenberg after a 1962 appellate court hearing in New Orleans. Credit: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, NYWT&S Collection, LC-DIG-ppmsca-05544.

Constance Baker Motley, interview with The Visionary Project, “My Inspiration to Be a Lawyer” (excerpt, video)

Constance Baker Motley was the first Black woman to argue at the Supreme Court and argued ten landmark civil rights cases, winning nine. She was a law clerk to Thurgood Marshall, aiding him in the case Brown v. Board of Education. Motley was also the first African-American woman appointed to the federal judiciary, serving as a United States District Judge of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York.

CitePrintShare“Constance Baker Motley: My Inspiration to Be a Lawyer.” YouTube, 22 Mar. 2010, www.youtube.com/watch?v=F8X_Hu0eaQc&t=1s.

Fannie Lou Hamer, Testimony Before the Credentials Committee, Democratic National Convention (1964)Atlantic City, New Jersey - August 22, 1964Transcript...My husband came, and said the plantation owner was raising Cain because I had tried to register. Before he quit talking the plantation owner came and said, "Fannie Lou, do you know - did Pap tell you what I said?"

And I said, "Yes, sir."

He said, "Well I mean that." He said, "If you don't go down and withdraw your registration, you will have to leave." Said, "Then if you go down and withdraw," said, "you still might have to go because we are not ready for that in Mississippi."

And I addressed him and told him and said, "I didn't try to register for you. I tried to register for myself."

I had to leave that same night.

….All of this is on account of we want to register, to become first-class citizens. And if the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated now, I question America. Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?

Thank you.

[For a transcript of the complete text and audio: https://americanradioworks.publicradio.org/features/sayitplain/flhamer.html]

Fannie Lou Hamer was a field organizer for SNCC. In 1964, she ran for Congress with the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. The MFDP brought an alternate slate of delegates to the Democratic Party convention, arguing that the all-white Mississippi Democratic Party was mired in racism and did not represent the rights and needs of all. As described by American Public Media, the Mississippi “incumbent was a white man who had been elected to office twelve times. In an interview with the Nation, Hamer said, ‘I'm showing the people that a Negro can run for office.’”

CitePrintShareTestimony Before the Credentials Committee by Fannie Lou Hamer | Say It Plain, https://americanradioworks.publicradio.org/features/sayitplain/flhamer.html.

Coretta Scott King, 10 Commandments on Vietnam (1968)Coretta Scott King, 10 Commandments on Vietnam (April 27, 1968) Central Park, New YorkTranscript….There is no reason why a nation as rich as ours should be blighted by poverty, disease, and illiteracy. It is plain that we don't care about our poor people except to exploit them as cheap labor and victimize them through excessive rents and consumer prices.

Our Congress passes laws which subsidize corporation farms, oil companies, airlines, and houses for suburbia. But when they turn their attention to the poor, they suddenly become concerned about balancing the budget and cut back on the funds for Head Start, Medicare, and mental health appropriations.

The most tragic of these cuts is the welfare section to the Social Security amendment, which freezes federal funds for millions of needy children, who are desperately poor but who do not receive public assistance. It forces mothers to leave their children and accept work or training, leaving their children to grow up in the streets as tomorrow's social problems. This law must be repealed, and I encourage you to join welfare mothers on May 12th, Mother's Day and call upon Congress to establish a guaranteed annual income, instead of these racist and archaic measures, these measures which dehumanize God's children and create more social problems than they solve.

We will be marching toward Washington soon. On Thursday, May 2nd we will return to Memphis to begin where my husband was slain and kick off his Poor People's campaign.

I would now like to address myself to the women. The woman power of this nation can be the power which makes us whole and heals the rotten community, now so shattered by war and poverty and racism. I have great faith in the power of women who will dedicate themselves whole-heartedly to the task of remaking our society.

I believe that the women of this nation and of the world are the best and last hope for a world of peace and brotherhood….

A musician and music educator, Coretta Scott King married Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1953. They had four children, and she traveled throughout the country and the world as an advocate for social justice with Dr. King.

This speech followed the assassination of Dr. King by just a few weeks. She used notes he had written for the speech, which she found in a jacket pocket of his after his death.

CitePrintShare“Coretta Scott King -- 10 Commandments on Vietnam.” American Rhetoric, 24 April 2022, https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/corettascottkingvietnamcommandments.htm.

Interview with Ella Baker (1968)Although she was a leader and architect of many of the key elements of the Civil Rights Movement, Ella Baker is often overlooked in coverage of the era. She helped to lead and organize the NAACP, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). In this interview, she describes the role she played and the occasional tensions among leaders of the movement.

The Civil Rights Documentary Project Oral History/Interview with Ella Baker (1968)

A [PARTIAL] Transcript of a Recorded Interview with Miss Ella Baker, Staff-Member-Consultant with SCEF, Southern Conference Educational Fund. By John Britton, Interviewer, Washington, D.C. June 19, 1968

Britton: So, what you're saying, then, is that the genesis of the idea for SCLC [the Southern Christian Leadership Conference] started in the minds of the people in the North, not in Montgomery?

Baker: That's correct. You see, if you recall, after the [Montgomery Bus Boycott] there was almost sort of a complete let down. Nothing was happening. In fact, after I had become associated with the leadership from Montgomery, question was raised about why there was this not-knowing, why there was no organizational machinery for making use of the people who had been involved in the boycott?

I think, to some extent as it seems to have been my characteristic in raising certain kinds of questions, I irritated Dr. King in raising this question. I raised it at a meeting at which he was speaking. I think his rationale was something to the effect that after a big demonstrative type of action, there was a natural let-down and a need for people to sort of catch their breath, you see, which, of course, I didn't quite agree with. But, nevertheless, this was what took place.

So, I don't think that the leadership of Montgomery was prepared to capitalize, let's put it, on the projection that had come out of the Montgomery situation. Certainly, they had not reached the point of developing an organizational format for the expansion of it. So discussions emanated, to a large extent, from up this way.

CitePrintShareBritton, John. “Veterans of the Civil Rights Movement -- Ella Baker.” Civil Rights Movement Archive, https://www.crmvet.org/nars/baker68.htm.

Shirley Chisholm, Speech on the floor of the House of Representatives, “I Am for the Equal Rights Amendment” (1970)Shirley Chisholm was the first Black woman elected to Congress and the first Black person to run for President from one of the nation’s two major political parties, in 1972. She was an educator and civil rights activist, and she served for decades as a legislator and political leader.

Shirley Chisholm, Speech on the floor of the House of Representatives, “I Am for the Equal Rights Amendment.” (1970)

It is time we act to assure full equality of opportunity to those citizens who, although in a majority, suffer the restrictions that are commonly imposed on minorities, to women.

The argument that this amendment will not solve the problem of sex discrimination is not relevant. If the argument were used against a civil rights bill, as it has been used in the past, the prejudice that lies behind it would be embarrassing. Of course laws will not eliminate prejudice from the hearts of human beings. But that is no reason to allow prejudice to continue to be enshrined in our laws — to perpetuate injustice through inaction.

The amendment is necessary to clarify countless ambiguities and inconsistencies in our legal system. For instance, the Constitution guarantees due process of law, in the 5th and 14th amendments. But the applicability of due process of sex distinctions is not clear. Women are excluded from some State colleges and universities. In some States, restrictions are placed on a married woman who engages in an independent business. Women may not be chosen for some juries. Women even receive heavier criminal penalties than men who commit the same crime.

…The time is clearly now to put this House on record for the fullest expression of that equality of opportunity which our founding fathers professed. They professed it, but they did not assure it to their daughters, as they tried to do for their sons.

The Constitution they wrote was designed to protect the rights of white, male citizens. As there were no black Founding Fathers, there were no founding mothers — a great pity, on both counts. It is not too late to complete the work they left undone. Today, here, we should start to do so.

CitePrintShareO'Halloran, Thomas J. “(1970) Shirley Chisholm, “I Am For the Equal Rights Amendment.” Blackpast, 24 July 2008, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/1970-shirley-chisholm-i-am-equal-rights-amendment/.

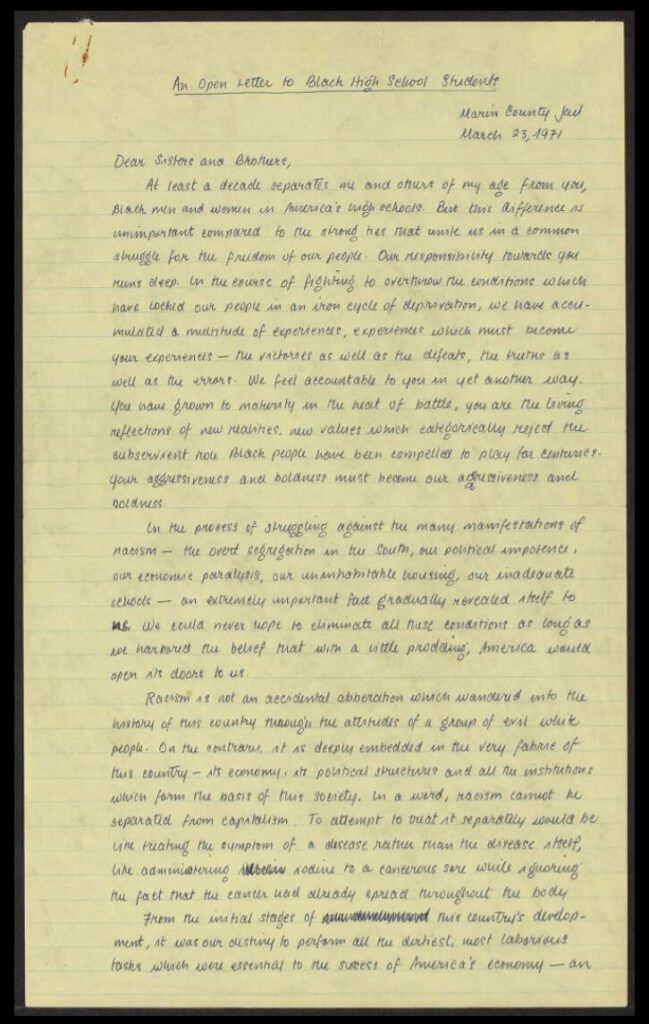

Angela Y. Davis, "An Open Letter to Black High School students” (1971)TranscriptDear Sisters and Brothers,

At least a decade separates me and others of my age from you, Black men and women in America’s high schools. But this difference is unimportant compared to the strong ties that unite us in a common struggle for the freedom of our people. Our responsibility towards you runs deep. In the course of fighting to overthrow the conditions which have locked our people in an iron cycle of deprivation, we have accumulated a multitude of experiences, experiences which must become your experiences – the victories as well as the defeats, the truths as well as the errors. We feel accountable to you in yet another way. You have grown to maturity in the heat of battle, you are the living reflections of new realities, new values which categorically reject the subservient role Black people have been compelled to play for centuries. Your aggressiveness and boldness must become our aggressiveness and boldness….

Angela Davis, scholar and member of the Black Panthers, wrote this letter while incarcerated in Marin County, California in 1971. Davis had been captured and arrested following an armed attack at the facility led by 17-year-old Jonathan Jackson, who was fighting for the release of his brother and other prisoners known as the “Soledad Brothers.” As described by journalist Antonio Mejias-Rentas, “Witnesses before a county grand jury testified that several of the weapons used in the courthouse takeover had been purchased by Davis, including a sawed-off shotgun that authorities said was used to kill Judge Haley. Although Davis had not been present, the grand jury returned an indictment charging her with kidnapping, murder and conspiracy. Davis never denied owning the weapons, but said she was not involved and had no knowledge of her weapons being used in the courthouse assault.”

CitePrintShareDavis, Angela. “An Open Letter to Black High School Students.” Harvard Mirador Viewer, 1971, iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:491078034$1i.

Mejías, Antonio. How Angela Davis Ended Up on the FBI Most Wanted List, 25 January 2023, https://www.history.com/news/angela-davis-fbi-most-wanted-list.

Condoleezza Rice, Speech to National Council of Negro Women (2001)A scholar of international affairs, Condoleezza Rice joined the administration of President George H.W. Bush as the Director for Soviet and Eastern European Affairs in the National Security Council. Later, after serving as the Provost of Stanford University, she became the first woman to direct the NSC, under then President George W. Bush. Her tenure included the attacks on 9/11 and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and in 2005 she became the first Black woman to serve as Secretary of State.

Condoleezza Rice, Speech to National Council of Negro Women, December 8, 2001 - Washington, D.C.

I could not be more honored than to receive the Bethune Award because I feel a great kinship with Mary McLeod Bethune and I think we all do. …It's extraordinary that a young, black woman from South Carolina could found a college and be its president for almost four decades.

…I also feel a great kinship to Dr. Bethune and to this organization because we share a passion for education. There is no more important element for the United States of America than the promise of education. I'm a living example of what education can mean, because it goes back a long way in my family. I very often tell people that I should have been able to accomplish what I accomplished because I had grandparents and parents who understood the value of education.

Maybe some of you've heard me tell the story of Granddaddy Rice, a poor sharecropper's son in Ewtah – that's E-W-T-A-H - Alabama, who, somehow, in about 1919 decided he was going to get book learning. And so he asked people who came through how a colored man could get to college. And they said to him, "Well you see there's this college not too far away from here called Stillman College, and if you could get there, they take colored men into college." And so he saved up his cotton and he went off to Tuscaloosa, Alabama to go to college. He made it through his first year having paid for it with his cotton, but the second year he didn't have any more cotton, and they came and they asked him for tuition. And he said, "Well you see the problem is, I don't have any money." And they said, "Well, you'll have to leave." So he thought rather quickly and he said, "Well how are those boys going to college?" And they said, "Well, you see, they have what's called a scholarship and if you wanted to be a Presbyterian minister then you could have a scholarship too." And Granddaddy Rice said, "You know, that's exactly what I had in mind. And my family has been Presbyterian and it has been college-educated ever since.

My grandfather understood something, and so did my grandmother and my mother's parents, and that is that higher education, if you can attain it, is transforming. You may come from a poor family, you may come from a rural family, you may be first-generation college-educated, but once you are college-educated, the most important thing about you, in many ways, is that you're a college graduate and you are transformed. And I have to tell you that if I have a concern at all today in America, it is that we have got to find a way to pass on that promise to children, no matter what their circumstances, because it's just got to be the case in America that it does not matter where you came from, it only matters where you're going.

CitePrintShareMedia, American Public. “American Radioworks - Say It Plain, Say It Loud.” APM Reports - Investigations and Documentaries from American Public Media, americanradioworks.publicradio.org/features/blackspeech/crice.html.

Education for American Democracy

The Harlem Renaissance was a cultural, economic, social, and political era that advanced the African American community and the rest of American society in myriad ways. Generally understood to stretch from the end of World War I to the 1930s, the Harlem Renaissance spoke to the hearts and minds of Americans from every aspect of life. The black middle class was increasing, and more educational opportunities were available to blacks. African heritage and roots were embraced by the movement’s young writers, artists, and musicians, who found in Harlem a place to express themselves. In addition, the LGBT community was prominent throughout the Harlem Renaissance. The Harlem Renaissance ended in the 1930s after the effects of the Great Depression set in. The economic downturn led to the departure of Harlem's prominent writers. Although the Harlem Renaissance lasted a brief time, it had an enduring influence on later black writers and helped to ease the way for the publication of works by black authors. Many of the artists that emerged from the Harlem Renaissance made a huge impact on the future of Modern Art. Some did not receive the recognition they deserved during their lifetime. However now, many are starting to be recognized for their contribution to American art.

The resources in this spotlight kit are intended for classroom use, and are shared here under a CC-BY-SA license. Teachers, please review the copyright and fair use guidelines.

The Roadmap

- Primary Resources by GenreEssays and Poems (9)Visual Art (5)Music (6)

- All 20 Primary Resources”For a Lady I Know,” Countee CullenCountee Cullen, Poet/WriterTranscript

For A Lady I Know

by Countee Cullen

She even thinks that up in heaven Her class lies late and snores While poor black cherubs rise at seven To do celestial chores.

Countee Cullen was adopted by a black pioneer activist minister and his wife. He was well-educated, earning his Masters in English and French from Harvard. Cullen won more major literary awards than any other black writer of the 1920s.

Though he wrote on universal themes such as love, religion, and death, Cullen believed in the richness and importance of his African American heritage and deftly applied traditional forms of verse, using melodic meter and rhyme, to African American themes.

CitePrintShareSummers, M. (2007, January 29). Countee Cullen (1903-1946). BlackPast.org. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/cullen-countee-1903-1946-0/

Cullen, Countee, and Paul Valery. “For A Lady I Know poem - Countee Cullen.” Best Poems, https://www.best-poems.net/countee_cullen/for_a_lady_i_know.html. Accessed 3 December 2022.

The Gift of Black Folk (excerpt), W.E.B. DuBoisW. E. B. Du Bois, Writer/ScholarTranscript“The time has not yet come for the great development of American Negro literature. The economic stress is too great and the racial persecution too bitter to allow the leisure and the poise for which literature calls. ‘The Negro in the United States is consuming all his intellectual energy in this gruelling race-struggle.’ …

On the other hand, never in the world has a richer mass of material been accumulated by a people than that which the Negroes possess today and are becoming increasingly conscious of. Slowly but surely they are developing artists of technic [sic] who will be able to use this material. The nation does not notice this for everything touching the Negro has hitherto been banned by magazines and publishers unless it took the form of caricature or bitter attack, or was so thoroughly innocuous as to have no literary flavor. This attitude shows signs of change at last.”

– from The Gift of Black Folk: The Negroes in the Making of America (1924)

William Edward Burghard (W.E.B) Du Bois was a sociologist, educator, and political activist. Educated at Fisk and Harvard Universities, DuBois wrote histories, sociological studies, informed sketches of African American life, and an autobiography. He believed education could end discrimination. DuBois organized the First International Congress of Colored People and was a founder of the NAACP.

CitePrintShareHistory.com Editors. W.E.B. Du Bois. Q. E. Television. (2009). https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/w-e-b-du-bois

Du Bois, W. E. B. (William Edward Burghardt). “The Gift of Black Folk: The Negroes in the Making of America.” The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Gift of Black Folk, by W. E. Burghardt DuBois., 29 Nov. 2022, https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/66398/pg66398-images.html#CHAPTER_VIII.

”Dead Fires,” Jessie Redmon FausetJessie Redmon Fauset, WriterTranscriptDead Fires (1922)

If this is peace, this dead and leaden thing,

Then better far the hateful fret, the sting.

Better the wound forever seeking balm

Than this gray calm!

Is this pain's surcease? Better far the ache,

The long-drawn dreary day, the night's white wake,

Better the choking sigh, the sobbing breath

Than passion's death!

As the literary editor of the NAACP’s Crisis magazine (1919 - 1926), Jessie Redman Fauset was one of three people Langston Hughes credited with “mid-wif{ing} the so-called New Negro literature into being. Kind and critical…they nursed us along until our books were born.” Redmon, among the first African Americans to be graduated (Phi Beta Kappa) from Cornell University, wrote books of her own as well.

CitePrintShareThomas, C. (2021, June 29). Jessie R. Fauset (1882-1961). BlackPast.org.

Fauset, Jessie Redmon. “Dead Fires by Jessie Redmon Fauset - Poems.” Academy of American Poets, https://poets.org/poem/dead-fires. Accessed 3 December 2022.

“The Principles Of The Universal Negro Improvement Association, ” Marcus GarveyMarcus Garvey, Writer/ActivistTranscript“We represent a new line of thought among Negroes. Whether you call it advanced thought or reactionary thought, I do not care. If it is reactionary for people to seek independence in government, then we are reactionary. If it is advanced thought for people to seek liberty and freedom, then we represent the advanced school of thought among the Negroes of this country.”

– (1922) Marcus Garvey, “The Principles Of The Universal Negro Improvement Association”

Marcus Garvey, the promoter of Pan-Africanism and black pride, had a vision of economic independence for his people. Those who followed him were called Garveyites. He was the founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, (UNIA) the single largest black organization ever. In the 1920s and 30s, the UNIA had an estimated six million followers around the world.

CitePrintShareSimba, M. (2007, February 05). Marcus Garvey (1887-1940). BlackPast.org. https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/garvey-marcus-1887-1940/

“(1922) Marcus Garvey, "The Principles of The Universal Negro Improvement Association" •.” Blackpast, 22 March 2007, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/1922-marcus-garvey-principles-universal-negro-improvement-association/. Accessed 3 December 2022.

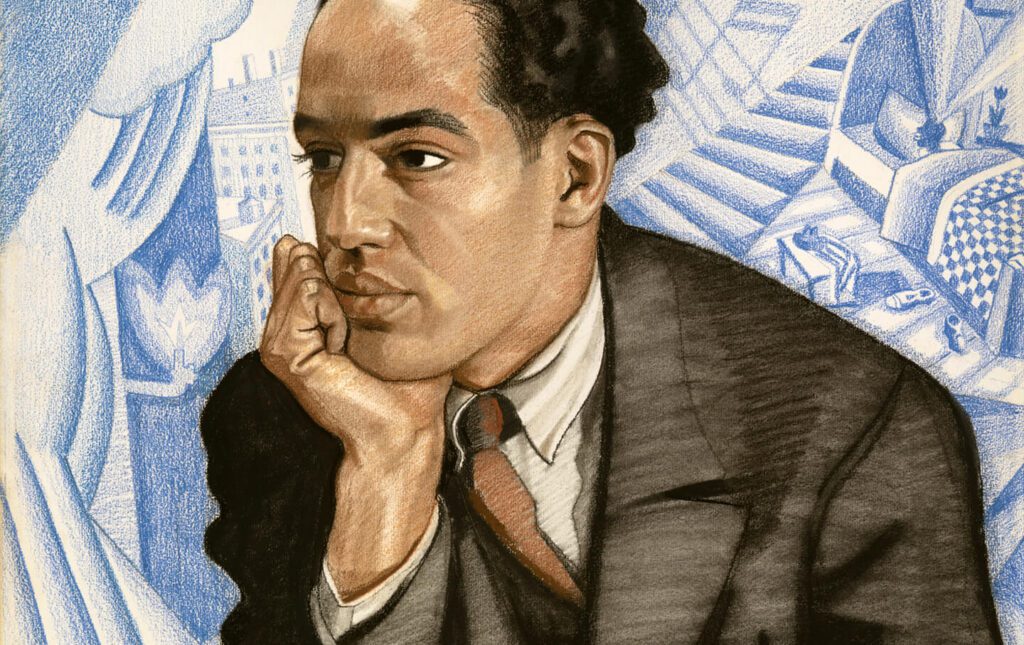

”I, Too,” Langston HughesLangston Hughes, Poet/WriterTranscriptI, Too (1926)

I, too, sing America.I am the darker brother.

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.

Tomorrow,

I'll be at the table

When company comes.

Nobody'll dare

Say to me,

“Eat in the kitchen,”

Then.

Besides,

They'll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamed—

I, too, am America.

Langston Hughes was known as the “Poet Laureate of Harlem.” One of the first African Americans to support himself solely as a writer. Hughes blended the sounds of jazz into his poetry. He focused on the need for artistic independence and racial pride.

CitePrintShareSummers, contributed by: Martin. “Langston Hughes (1902-1967)” 2 Feb. 2020, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/hughes-langston-1902-1967/.

Letter to Countee Cullen, Zora Neale HurstonZora Neale Hurston, WriterTranscript“I have the nerve to walk my own way, however hard, in my search for reality, rather than climb upon the rattling wagon of wishful illusions."

- Letter from Zora Neale Hurston to Countee Cullen

Zora Neale Hurston was a brilliant, multifaceted chronicler of African American life as she saw it. Her dominant influence was her hometown of Eatonville, Florida, the first incorporated all-black township in the United States. Ms. Hurston grew up there independent and self-reliant, her imagination fired by the rich oral traditions of the rural African American South and her sense of self undistorted by prejudice. She later pursued field studies of southern black folklore that would be documented in her book Mules and Men (1935) and would permeate much of her best fiction.

CitePrintSharePatterson, T. (2007, January 29). Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960). BlackPast.org. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/hurston-zora-neale-1891-1960/

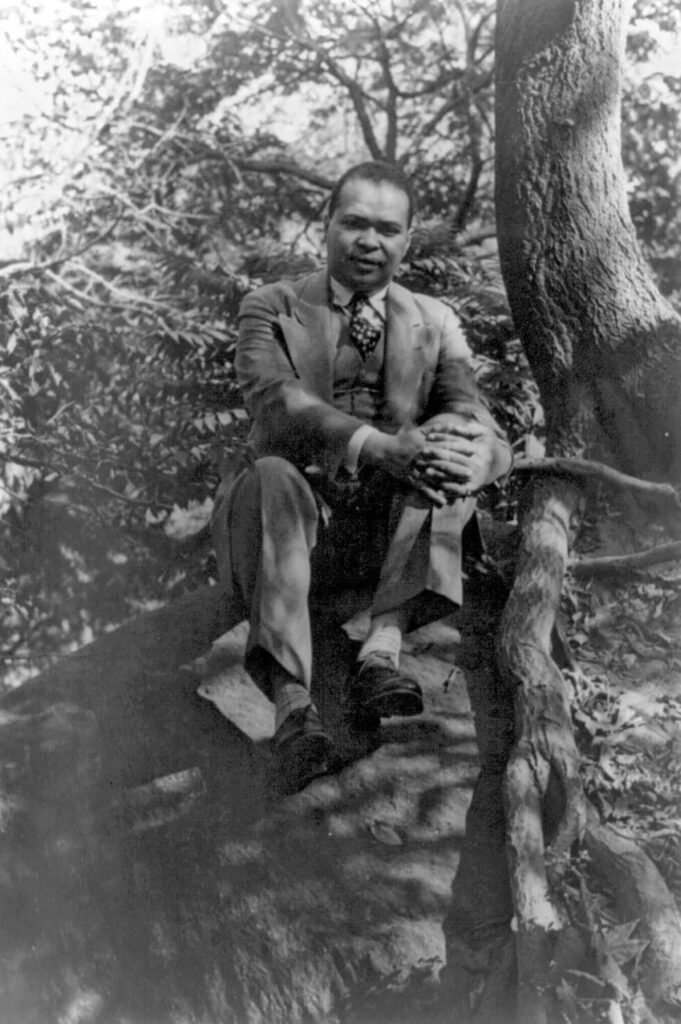

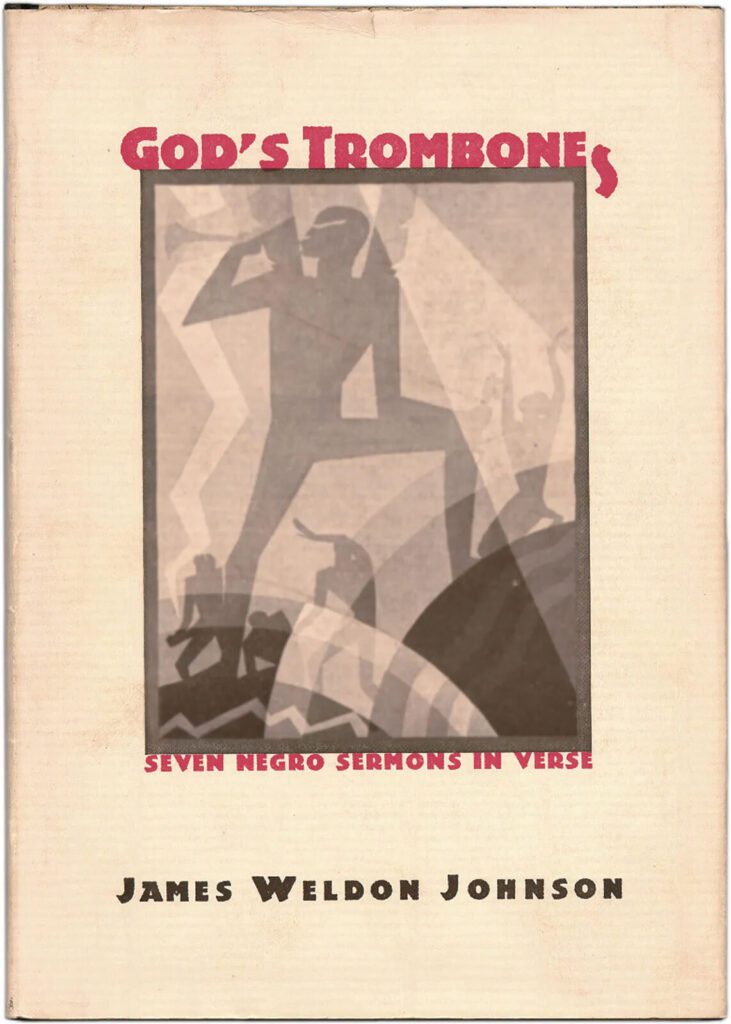

”Harlem: the Culture Capital,” James Weldon JohnsonJames Weldon Johnson, WriterTranscript“To my mind, Harlem is more than a Negro community; it is a large scale laboratory experiment in the race problem. The statement has often been made that if Negroes were transported to the North in large numbers the race problem with all of its acuteness and with new aspects would be transferred with them. Well, 175,000 Negroes live closely together in Harlem, in the heart of New York – 75,000 more than live in any Southern City – and do so without any race friction…New York guarantees its Negro citizens the fundamental rights of American citizenship and protects them in the exercise of those rights. In return the Negro loves New York and is proud of it, and contributes in his way to its greatness. He still meets with discriminations, but possessing the basic rights, he knows that these discriminations will be abolished.

I believe that the Negro’s advantages and opportunities are greater in Harlem than in any other place in the country, and that Harlem will become the intellectual, the cultural and the financial center for Negroes of the United States, and will exert a vital influence upon all Negro peoples.”

– from “Harlem: the Culture Capital” in The New Negro (Alain Locke, ed.)

James Weldon Johnson was a poet (God’s Trombones) and an influential anthologist (The Book of American Negro Poetry). The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, his only novel and perhaps his best-known literary work, was first published in 1912, four years before he became field secretary of the NAACP. Over the next sixteen years, Johnson expanded NAACP membership and coordinated its programs, resigning, and finally accepting a professorship at Fisk University. He continued to write poetry, essays, and magazine articles throughout all those years, as well as the historical study of Black Manhattan and his autobiography, Along this Way.

CitePrintShareBritannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2021, June 22). James Weldon Johnson. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/James-Weldon-Johnson

Johnson, James Weldon. “Harlem: the Culture Capital.” The New Negro, Atheneum, 1968.

”Enter the New Negro,” Alain LockeAlain Locke, Writer/EducatorTranscript“With this renewed self-respect and self-dependence, the life of the Negro community is bound to enter a new dynamic phase, the buoyancy from within compensating for whatever pressure there may be of conditions from without. The migrant masses, shifting from countryside to city, hurdle several generations of experience at a leap, but more important, the same thing happens spiritually in the lifeattitudes and self-expression of the Young Negro, in his poetry, his art, his education and his new outlook, with the additional advantage, of course, of the poise and greater certainty of knowing what it is all about. From this comes the promise and warrant of a new leadership.”

–From “Enter the New Negro” Survey Graphic, March 1925: Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro

Alain Locke is referred to as the “Father of the Harlem Renaissance.” Locke’s book The New Negro made him the leader and principal spokesman of the “New Negro Movement, “ which he encouraged through numerous essays and art and literary reviews. He also was deeply involved in efforts to help African-American artists and writers- including Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Aaron Douglas, and Richmond Barthe-find financial support.

CitePrintShareWatson, E. (2007, January 18). Alain Locke (1886-1954). BlackPast.org. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/locke-alain-1886-1954/

Reiss, Winold. “"Enter the New Negro," Survey Graphic, March 1925, Alain Locke.” National Humanities Center, http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/maai3/migrations/text8/lockenewnegro.pdf. Accessed 3 December 2022.

”America,” Claude McKayClaude McKay, Poet/WriterTranscriptAmerica

BY CLAUDE MCKAY

Although she feeds me bread of bitterness,

And sinks into my throat her tiger’s tooth,

Stealing my breath of life, I will confess

I love this cultured hell that tests my youth.

Her vigor flows like tides into my blood,

Giving me strength erect against her hate,

Her bigness sweeps my being like a flood.

Yet, as a rebel fronts a king in state,

I stand within her walls with not a shred

Of terror, malice, not a word of jeer.

Darkly I gaze into the days ahead,

And see her might and granite wonders there,

Beneath the touch of Time’s unerring hand,

Like priceless treasures sinking in the sand.

– "America" from Liberator (1921).

Source: Liberator (The Library of America, 1921)

Claude McKay was born in Jamaica on September 15, 1889. In 1920, he published Spring in New Hampshire in England. Many of the poems from Spring in New Hampshire were used in his Harlem Shadows (published 1922, in New York). Harlem Shadows showcased a new African American voice. It was bold and angry. It discussed the racial prejudices that McKay experienced when he arrived in America.

CitePrintShareSamuels, W. (2007, January 19). Claude McKay (1889-1948). BlackPast.org. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/mckay-claude-1889-1948/

McKay, Claude, and Becca Klaver. “America by Claude McKay.” Poetry Foundation, 4 July 2022, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44691/america-56d223e1ac025. Accessed 27 November 2022.

”Aspiration,” Aaron DouglasAaron Douglas’ work focused on social issues in the United States, like segregation. Douglas often references history in his work. Douglas examines slavery, African heritage, and the future of society. Douglas’ paintings often symbolized the history and struggle of the African American community. Douglas’ paintings included monochromatic color, silhouetted figures, and geometric forms.

CitePrintShareJohnson, T. (2007, January 17). Aaron Douglas (1898-1979). BlackPast.org. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/douglas-aaron-1898-1979/

Douglas, Aaron. “Aspiration by Aaron Douglas.” Obelisk Art History, https://arthistoryproject.com/artists/aaron-douglas/aspiration/. Accessed 27 November 2022.

”Midsummer Night in Harlem,” Palmer HaydenPalmer Hayden was an extremely talented painter. Early in his career, he focused mostly on landscapes. In 1927, he moved to Paris and grew greatly as an artist. In 1932, he returned to the U.S. and changed his focus to small-town African Americans. He has been criticized for perpetuating stereotypes of African American physical features.

CitePrintShareBlumberg, N. (2022, February 14). Palmer Hayden. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Palmer-Hayden

ADAMS, DERRICK. “PALMER C. HAYDEN – WEST HARLEM ART FUND.” West Harlem Art Fund, 24 January 2019, https://westharlem.art/2019/01/24/palmer-c-hayden/. Accessed 27 November 2022.

”The Migration of the Negro,” Jacob LawrenceAs a teenager, Jacob Lawrence took art classes at the Uptown Art Laboratory, finding mentors in Harlem Renaissance artists Charles Alston and Augusta Savage. Lawrence explored issues central to African American history and daily life. Lawrence created The Migration Series based on the Great Migration.

Lawrence studied at the Schomburg Library and eventually gained employment as a painter for the Federal Art Project.

CitePrintShareThomas, B. (2007, January 21). Jacob Lawrence & Gwendolyn Knight. BlackPast.org. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/people-african-american-history/lawrence-jacob-1917-2000-lawrence-gwendolyn-knight-1913-2005/

Grim, Ruth, and Gary R. Libby. “Jacob Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance.” Museum of Arts & Science, 6 February 2019, https://www.moas.org/Jacob-Lawrence-and-the-Harlem-Renaissance-1-57.html. Accessed 3 December 2022.

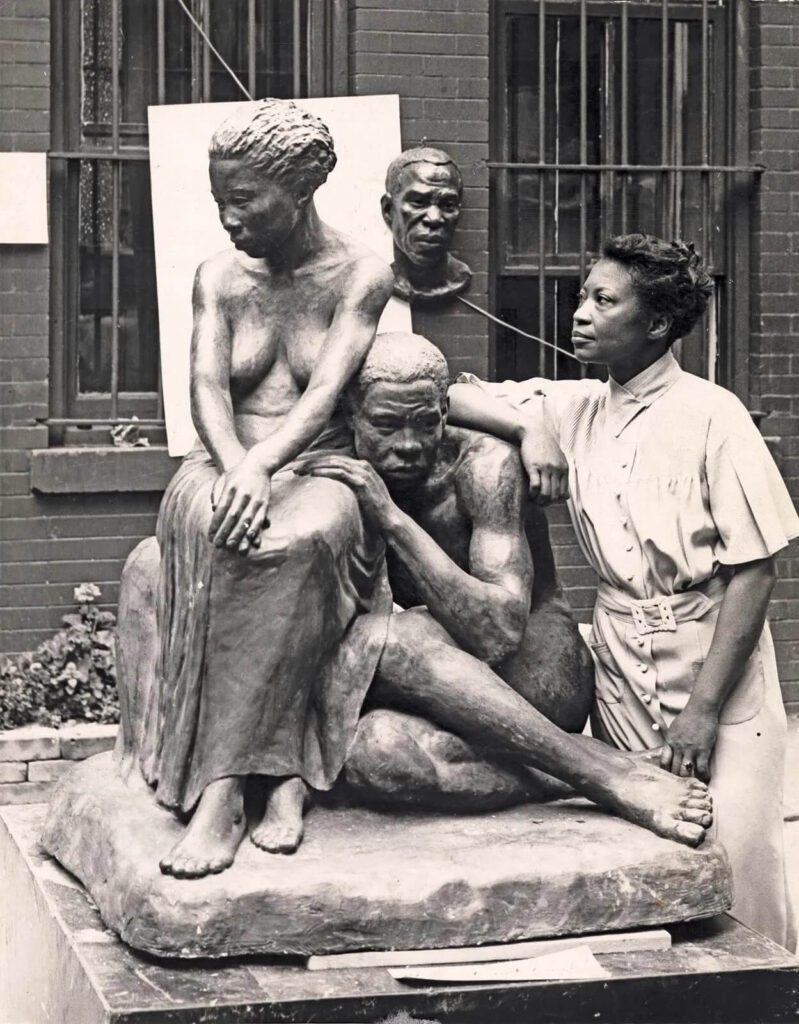

”Realization,” Augusta SavageAugusta Savage with her sculpture Realization, circa 1938.Augustus Savage was recognized on the Harlem scene after being commissioned to sculpt the bust of W.E.B. Dubois. She won a scholarship to Academie de la Grande Chaumiere in Paris. Savage opened the largest free art program in Harlem, and students like Jacob Lawerence attended Savage School of Arts.

CitePrintShareAndrew Herman. Augusta Savage with her sculpture Realization, circa 1938. Federal Art Project, Photographic Division collection, circa 1920-1965. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

https://www.si.edu/object/augusta-savage-her-sculpture-realization:AAADCD_item_2371

”Evening Attire,” James VanDerZeeJames VanDerZee became interested in photography as a teenager. He told the history of African Americans with his photographs. He is noted for documenting African American middle-class life in Harlem. He documented the work of Marcus Garvey in 1924, and in 1969, his work was a part of the Harlem on My Mind exhibition at the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art.

CitePrintShareWatson, contributed by: Elwood. James Van Der Zee (1886-1983), 15 July 2019, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/van-der-zee-james-1886-1983/.

“James VanDerZee | Smithsonian American Art Museum.” Smithsonian American Art Museum, https://americanart.si.edu/artist/james-vanderzee-6593. Accessed 27 November 2022.

”What a Wonderful World,” Louis ArmstrongLouis Armstrong, MusicianLouis Daniel Armstrong Is one of the foremost jazz trumpeters in American music. Born in poverty, Armstrong was raised by his grandmother in New Orleans, a city known for its bands and jazz musicians. After 1931, Louis Armstrong became the best-known jazz musician in the world. He toured Europe several times and appeared in a number of movies.

CitePrintShareButler, G. (2007, July 17). Louis Armstrong (1901-1971). BlackPast.org. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/armstrong-louis-daniel-1901-1971/

”Jumpin’ Jive,” Cab CallowayCab Calloway, MusicianCab Calloway was an energetic bandleader who took the Cotton Club by storm. He appeared in several movies and radio broadcasts. Mr. Calloway was awarded the Nation Medal of Arts by President Bill Clinton in 1993.

CitePrintShareErickson, S. (2008, June 14). Cab Calloway (1907-1994). BlackPast.org. htt/african-american-historyps://www.blackpast.org/calloway-cab-1907-1994/

”Take the ‘A’ Train,” Edward “Duke” EllingtonEdward “Duke” Ellington, Singer/ BandLeaderComposer, pianist, and bandleader Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington was one of the great innovators of modern American music, taking big-band jazz into realms of harmony, form, and tonal color. Though ever seeking to grow and expand as a musician, Ellington seldom strayed from the heart of the matter: “If it sounds good,” he said, “it is good.” One of Ellington’s signature songs, “Take the ‘A’ Train” refers to a New York subway line and pays homage to Harlem, its destination.

CitePrintShareButler, G. (2007, May 19). Edward “Duke” Ellington (1899-1974). BlackPast.org. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/ellington-edward-duke-1899-1974/

”Strange Fruit,” Billie HolidayBillie Holiday, SingerBorn in 1915, Billie Holiday became one of the most influential jazz singers of her time. Holiday was discovered at the age of 18, singing in a nightclub in Harlem. One of her most famous songs, “Strange Fruit,” was banned by many radio stations when it debuted; the song tells the story of the lynching of African Americans. Drug addiction affected both her career and her personal life, and it led to her untimely death in 1959.

CitePrintShareButler, G. (2007, June 16). Billie Holiday (1915-1959). BlackPast.org. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/holliday-billie-1915-1959

”Deep Moaning Blues,” Gertrude “Ma” RaineyGertrude “Ma” Rainey, Singer/Entertainer“Ma” Rainey was known as the Mother of the Blues; she was the first woman to introduce blues in her performances, and she established her own entertainment company in 1917.

CitePrintShareBrandman, Mariana. “Gertrude ‘Ma’ Rainey.” National Women’s History Museum. 2021. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/gertrude-ma-rainey

”St. Louis Blues,” Bessie SmithBessie Smith, SingerThe 1920s in America were a golden age of the powerful blueswoman. At the pinnacle stood Bessie Smith, whose personal and musical power pushed the boundaries of both female and African American expression for a new mass audience.

CitePrintShareJackson, E. (2011, January 08). Bessie Smith (1894-1937). BlackPast.org. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/bessie-smith-1894-1937/

Education for American Democracy

Download the Roadmap and Report

Download the Educating for American Democracy Roadmap and Report Documents

Get the Roadmap and Report to unlock the work of over 300 leading scholars, educators, practitioners, and others who spent thousands of hours preparing this robust framework and guiding principles. The time is now to prioritize history and civics.

Your contact information will not be shared, and only used to send additional updates and materials from Educating for American Democracy, from which you can unsubscribe.

We the People

This theme explores the idea of “the people” as a political concept–not just a group of people who share a landscape but a group of people who share political ideals and institutions.

Institutional & Social Transformation

This theme explores how social arrangements and conflicts have combined with political institutions to shape American life from the earliest colonial period to the present, investigates which moments of change have most defined the country, and builds understanding of how American political institutions and society changes.

Contemporary Debates & Possibilities

This theme explores the contemporary terrain of civic participation and civic agency, investigating how historical narratives shape current political arguments, how values and information shape policy arguments, and how the American people continues to renew or remake itself in pursuit of fulfillment of the promise of constitutional democracy.

Civic Participation

This theme explores the relationship between self-government and civic participation, drawing on the discipline of history to explore how citizens’ active engagement has mattered for American society and on the discipline of civics to explore the principles, values, habits, and skills that support productive engagement in a healthy, resilient constitutional democracy. This theme focuses attention on the overarching goal of engaging young people as civic participants and preparing them to assume that role successfully.

Our Changing landscapes

This theme begins from the recognition that American civic experience is tied to a particular place, and explores the history of how the United States has come to develop the physical and geographical shape it has, the complex experiences of harm and benefit which that history has delivered to different portions of the American population, and the civics questions of how political communities form in the first place, become connected to specific places, and develop membership rules. The theme also takes up the question of our contemporary responsibility to the natural world.

A New Government & Constitution

This theme explores the institutional history of the United States as well as the theoretical underpinnings of constitutional design.

A People in the World

This theme explores the place of the U.S. and the American people in a global context, investigating key historical events in international affairs,and building understanding of the principles, values, and laws at stake in debates about America’s role in the world.

The Seven Themes

The Seven Themes provide the organizational framework for the Roadmap. They map out the knowledge, skills, and dispositions that students should be able to explore in order to be engaged in informed, authentic, and healthy civic participation. Importantly, they are neither standards nor curriculum, but rather a starting point for the design of standards, curricula, resources, and lessons.

Driving questions provide a glimpse into the types of inquiries that teachers can write and develop in support of in-depth civic learning. Think of them as a starting point in your curricular design.

Learn more about inquiry-based learning in the Pedagogy Companion.

Sample guiding questions are designed to foster classroom discussion, and can be starting points for one or multiple lessons. It is important to note that the sample guiding questions provided in the Roadmap are NOT an exhaustive list of questions. There are many other great topics and questions that can be explored.

Learn more about inquiry-based learning in the Pedagogy Companion.

The Seven Themes

The Seven Themes provide the organizational framework for the Roadmap. They map out the knowledge, skills, and dispositions that students should be able to explore in order to be engaged in informed, authentic, and healthy civic participation. Importantly, they are neither standards nor curriculum, but rather a starting point for the design of standards, curricula, resources, and lessons.

The Five Design Challenges

America’s constitutional politics are rife with tensions and complexities. Our Design Challenges, which are arranged alongside our Themes, identify and clarify the most significant tensions that writers of standards, curricula, texts, lessons, and assessments will grapple with. In proactively recognizing and acknowledging these challenges, educators will help students better understand the complicated issues that arise in American history and civics.

Motivating Agency, Sustaining the Republic

- How can we help students understand the full context for their roles as civic participants without creating paralysis or a sense of the insignificance of their own agency in relation to the magnitude of our society, the globe, and shared challenges?

- How can we help students become engaged citizens who also sustain civil disagreement, civic friendship, and thus American constitutional democracy?

- How can we help students pursue civic action that is authentic, responsible, and informed?

America’s Plural Yet Shared Story

- How can we integrate the perspectives of Americans from all different backgrounds when narrating a history of the U.S. and explicating the content of the philosophical foundations of American constitutional democracy?

- How can we do so consistently across all historical periods and conceptual content?

- How can this more plural and more complete story of our history and foundations also be a common story, the shared inheritance of all Americans?

Simultaneously Celebrating & Critiquing Compromise

- How do we simultaneously teach the value and the danger of compromise for a free, diverse, and self-governing people?

- How do we help students make sense of the paradox that Americans continuously disagree about the ideal shape of self-government but also agree to preserve shared institutions?

Civic Honesty, Reflective Patriotism

- How can we offer an account of U.S. constitutional democracy that is simultaneously honest about the wrongs of the past without falling into cynicism, and appreciative of the founding of the United States without tipping into adulation?

Balancing the Concrete & the Abstract

- How can we support instructors in helping students move between concrete, narrative, and chronological learning and thematic and abstract or conceptual learning?

Each theme is supported by key concepts that map out the knowledge, skills, and dispositions students should be able to explore in order to be engaged in informed, authentic, and healthy civic participation. They are vertically spiraled and developed to apply to K—5 and 6—12. Importantly, they are not standards, but rather offer a vision for the integration of history and civics throughout grades K—12.

Helping Students Participate

- How can I learn to understand my role as a citizen even if I’m not old enough to take part in government? How can I get excited to solve challenges that seem too big to fix?

- How can I learn how to work together with people whose opinions are different from my own?

- How can I be inspired to want to take civic actions on my own?

America’s Shared Story

- How can I learn about the role of my culture and other cultures in American history?

- How can I see that America’s story is shared by all?

Thinking About Compromise

- How can teachers teach the good and bad sides of compromise?

- How can I make sense of Americans who believe in one government but disagree about what it should do?

Honest Patriotism

- How can I learn an honest story about America that admits failure and celebrates praise?

Balancing Time & Theme

- How can teachers help me connect historical events over time and themes?

The Six Pedagogical Principles

EAD teacher draws on six pedagogical principles that are connected sequentially.

Six Core Pedagogical Principles are part of our Pedagogy Companion. The Pedagogical Principles are designed to focus educators’ effort on techniques that best support the learning and development of student agency required of history and civic education.

EAD teachers commit to learn about and teach full and multifaceted historical and civic narratives. They appreciate student diversity and assume all students’ capacity for learning complex and rigorous content. EAD teachers focus on inclusion and equity in both content and approach as they spiral instruction across grade bands, increasing complexity and depth about relevant history and contemporary issues.

Growth Mindset and Capacity Building

EAD teachers have a growth mindset for themselves and their students, meaning that they engage in continuous self-reflection and cultivate self-knowledge. They learn and adopt content as well as practices that help all learners of diverse backgrounds reach excellence. EAD teachers need continuous and rigorous professional development (PD) and access to professional learning communities (PLCs) that offer peer support and mentoring opportunities, especially about content, pedagogical approaches, and instruction-embedded assessments.

Building an EAD-Ready Classroom and School

EAD teachers cultivate and sustain a learning environment by partnering with administrators, students, and families to conduct deep inquiry about the multifaceted stories of American constitutional democracy. They set expectations that all students know they belong and contribute to the classroom community. Students establish ownership and responsibility for their learning through mutual respect and an inclusive culture that enables students to engage courageously in rigorous discussion.

Inquiry as the Primary Mode for Learning

EAD teachers not only use the EAD Roadmap inquiry prompts as entry points to teaching full and complex content, but also cultivate students’ capacity to develop their own deep and critical inquiries about American history, civic life, and their identities and communities. They embrace these rigorous inquiries as a way to advance students’ historical and civic knowledge, and to connect that knowledge to themselves and their communities. They also help students cultivate empathy across differences and inquisitiveness to ask difficult questions, which are core to historical understanding and constructive civic participation.

Practice of Constitutional Democracy and Student Agency

EAD teachers use their content knowledge and classroom leadership to model our constitutional principle of “We the People” through democratic practices and promoting civic responsibilities, civil rights, and civic friendship in their classrooms. EAD teachers deepen students’ grasp of content and concepts by creating student opportunities to engage with real-world events and problem-solving about issues in their communities by taking informed action to create a more perfect union.

Assess, Reflect, and Improve

EAD teachers use assessments as a tool to ensure all students understand civics content and concepts and apply civics skills and agency. Students have the opportunity to reflect on their learning and give feedback to their teachers in higher-order thinking exercises that enhance as well as measure learning. EAD teachers analyze and utilize feedback and assessment for self-reflection and improving instruction.

EAD teachers commit to learn about and teach full and multifaceted historical and civic narratives. They appreciate student diversity and assume all students’ capacity for learning complex and rigorous content. EAD teachers focus on inclusion and equity in both content and approach as they spiral instruction across grade bands, increasing complexity and depth about relevant history and contemporary issues.

Growth Mindset and Capacity Building

EAD teachers have a growth mindset for themselves and their students, meaning that they engage in continuous self-reflection and cultivate self-knowledge. They learn and adopt content as well as practices that help all learners of diverse backgrounds reach excellence. EAD teachers need continuous and rigorous professional development (PD) and access to professional learning communities (PLCs) that offer peer support and mentoring opportunities, especially about content, pedagogical approaches, and instruction-embedded assessments.

Building an EAD-Ready Classroom and School

EAD teachers cultivate and sustain a learning environment by partnering with administrators, students, and families to conduct deep inquiry about the multifaceted stories of American constitutional democracy. They set expectations that all students know they belong and contribute to the classroom community. Students establish ownership and responsibility for their learning through mutual respect and an inclusive culture that enables students to engage courageously in rigorous discussion.

Inquiry as the Primary Mode for Learning

EAD teachers not only use the EAD Roadmap inquiry prompts as entry points to teaching full and complex content, but also cultivate students’ capacity to develop their own deep and critical inquiries about American history, civic life, and their identities and communities. They embrace these rigorous inquiries as a way to advance students’ historical and civic knowledge, and to connect that knowledge to themselves and their communities. They also help students cultivate empathy across differences and inquisitiveness to ask difficult questions, which are core to historical understanding and constructive civic participation.

Practice of Constitutional Democracy and Student Agency

EAD teachers use their content knowledge and classroom leadership to model our constitutional principle of “We the People” through democratic practices and promoting civic responsibilities, civil rights, and civic friendship in their classrooms. EAD teachers deepen students’ grasp of content and concepts by creating student opportunities to engage with real-world events and problem-solving about issues in their communities by taking informed action to create a more perfect union.

Assess, Reflect, and Improve

EAD teachers use assessments as a tool to ensure all students understand civics content and concepts and apply civics skills and agency. Students have the opportunity to reflect on their learning and give feedback to their teachers in higher-order thinking exercises that enhance as well as measure learning. EAD teachers analyze and utilize feedback and assessment for self-reflection and improving instruction.